How Doki Doki Literature Club frames you

Where we're going we don't need walls

This article spoils Doki Doki Literature Club in the first sentence, it presupposes you’ve played it, and goes on to spoil the narrative tricks the game uses to make its story meaningful. So if you haven’t played the game, get it (it’s free),make a pot of coffee, set aside four hours, play it, and then come back here and read this. Like the dentist, it’s good for you and in no way painful at all I promise I really do and I wouldn't lie to you xx

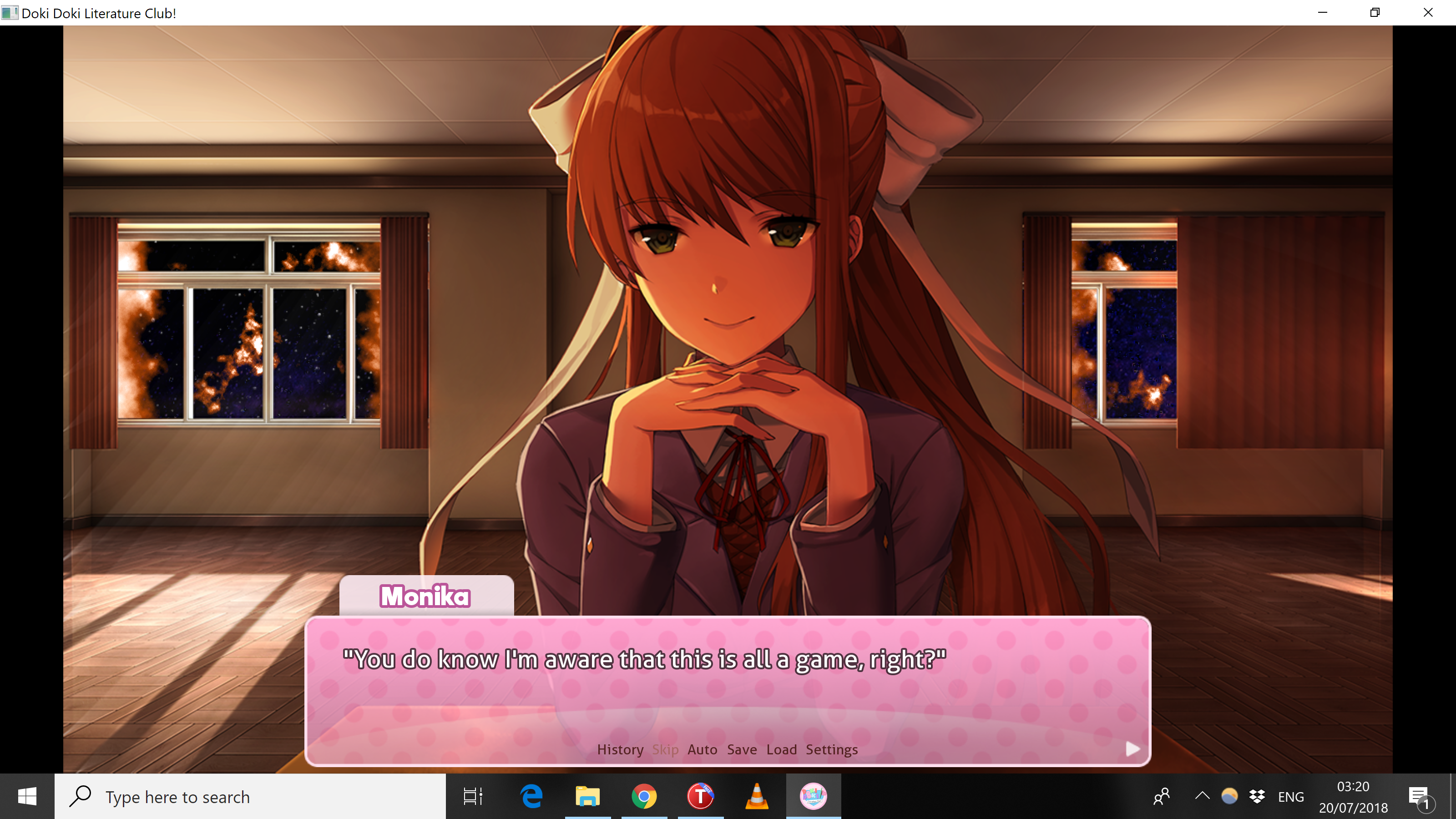

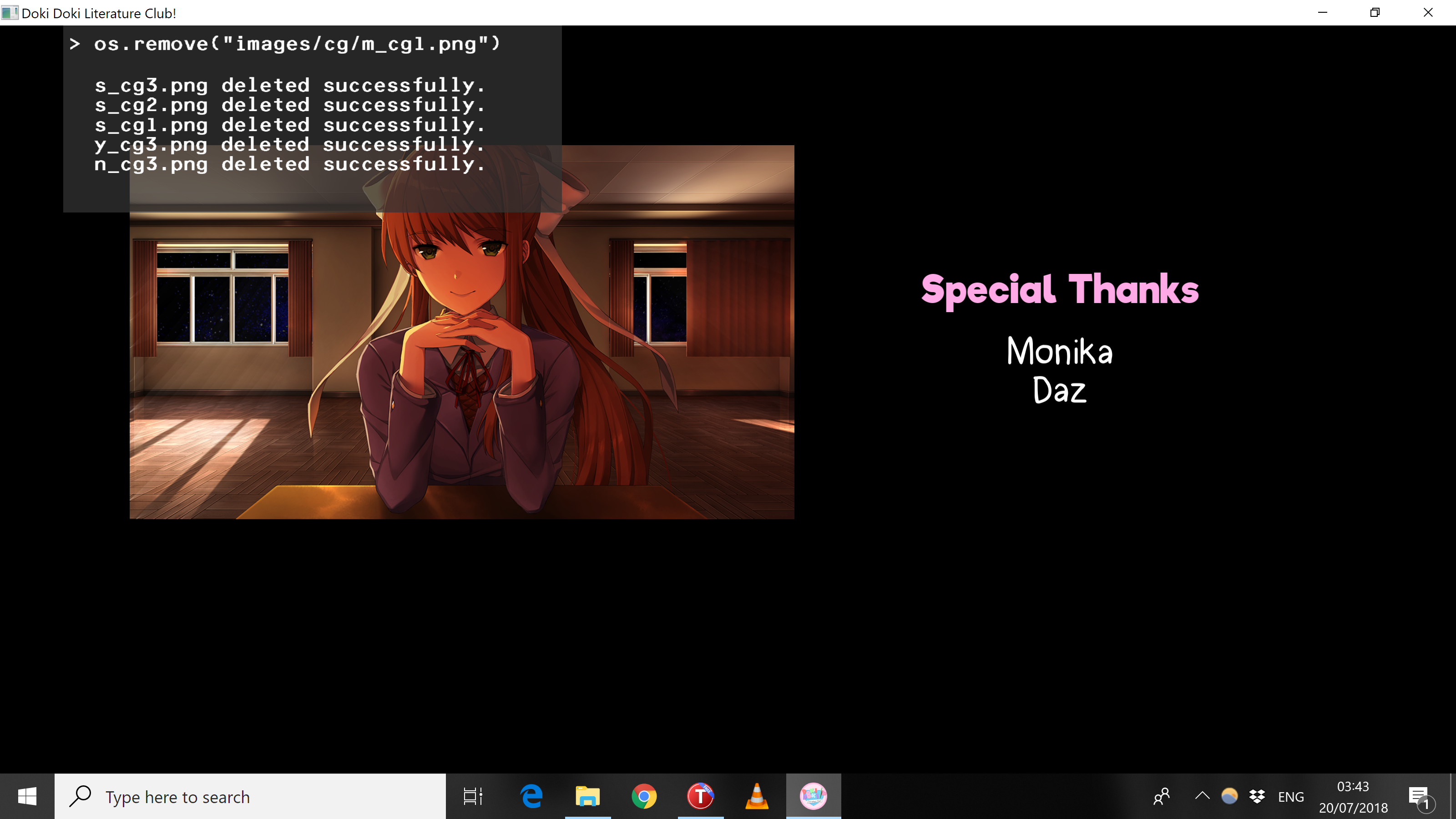

Doki Doki Literature Club framed me for Homicide. I remember the adrenaline, paranoia and thirst for a lovely quiet cup of straight gin tea that consumed me when I realised I’d have to delete Monika’s program files, effectively killing her. That rush was short lived. It didn't work. Monika had overtaken all the game’s files by that point; and decided to delete herself. Having tried and failed to kill her, was I now responsible for her suicide? “What a mindfuck” I thought, as the credits rolled and the game deleted itself.

The tricks that Doki uses to make its ending so impactful revolve around frames and framing. A game usually has one significant frame: Player-Game. With Mario, for example, your world is a side scrolling platform. You run, jump, pick up coins and fight fiendish turtles. In this, your “real” life doesn’t matter as you’re immersed and flowing towards a promised land of peaches. Mario is designed to tie you into loops and habits that encourage this immersive flow. They keep you in one frame, one plot, one narrative. Doki is the opposite of this. It’s designed to break you out of the Player-Game frame, and make you think about the other frames involved in gaming. Here, then, are the 5 frames that Doki uses to make the player guilty of manslaughter, if not full on murder.

Player-Game

The game presents itself as a dating sim/ visual novel, where your aim is to get one of the girls to love you forever. The whole thing is super Kawaii. Kawaii is a Japanese word with associations like doe-eyes, skirts, giggles, sweet cheeks and quaint stationary. The problem with Kawaii culture is that it tends to reduce teenage girls and their agency to the level of Pokémon. They have their own style, interests and personalities, but only one true motivation; to find a loving master who can “train” them. This genre attracts two kinds of people, those with a deep respect for the twee things in life (and fair enough) and you know, those with interests that are morally challenging for non-Mormons (see: the absolute filth that is Peach Beach Splash).

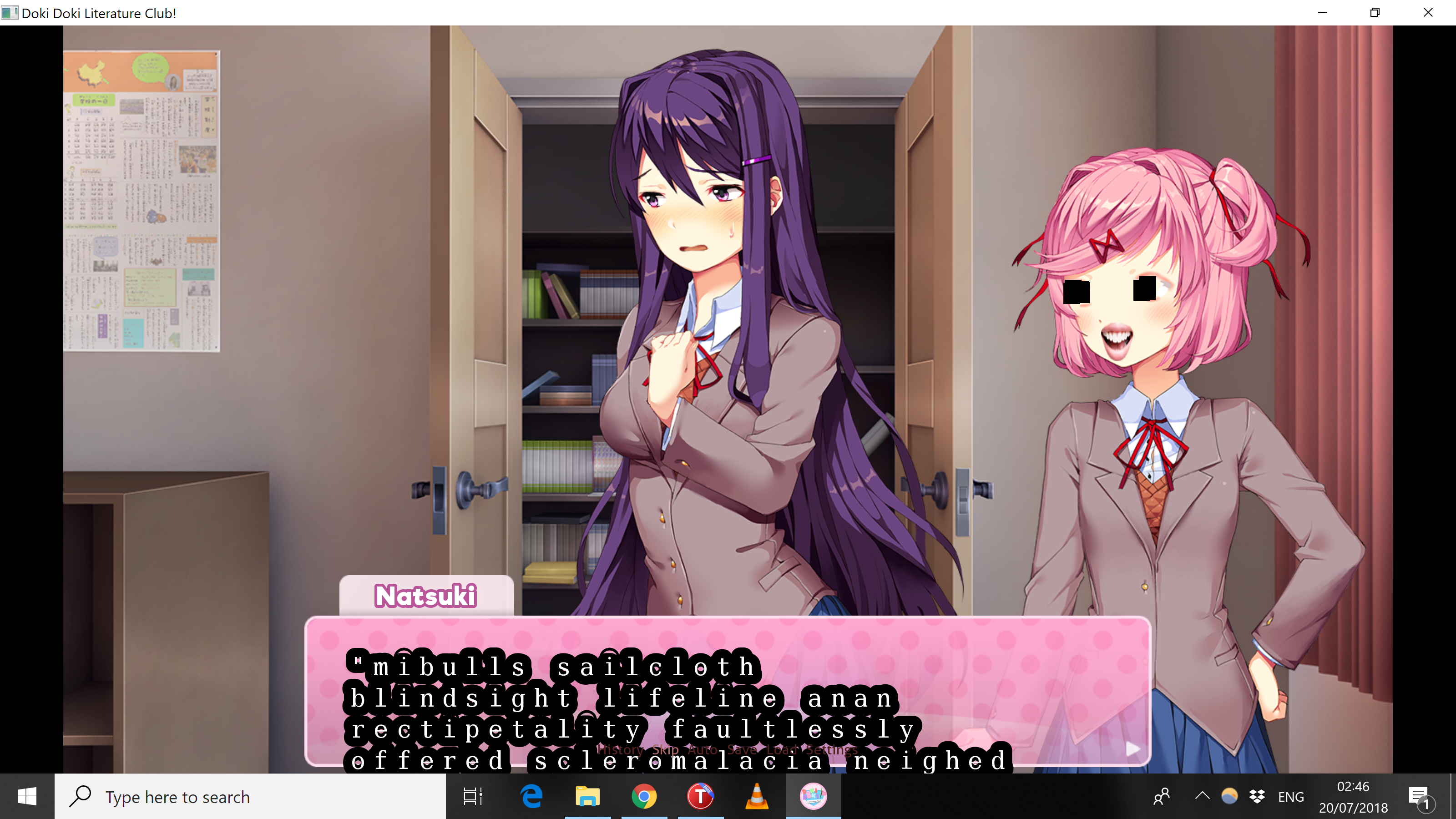

As you play through the sim, it seems like you can meaningfully impact the plot by writing poems with concepts the girls will like, or by choosing one girl to hang out with alone. This is a sham, because as you play Monika is slowly breaking bad and morphing into a schoolgirl version of SHODAN, taking control of the game's systems.

The emergence of her agency pushes the premises of the dating sim to its logical conclusion: What if Kawaii girls weren’t defined by the eternal repetition of archetypes? What if your choices had the consequences they have in real life? What if our motivations weren't muted by a fixed genre or loop? In manipulating the other girls into killing themselves, and in trying to win your heart, Monika gives us one possible answer. The structure of the game shatters. Its text, pacing, soundscape and characters blur and disintegrate into incoherence, forcing a new kind of story to emerge.

Player-EvilAsh

On starting the game, you’re given the narrative voice of a guy who says stuff like “I treat you like you deserve to be treated Yuri,” and who thinks about how he wants “more” from his relationships. This sets you up as a dodgy lad from Kyoto who’s into Pokémon for evil, will-to-power, reasons. Let’s call him “EvilAsh”. The initial framing of your character as that guy makes the choices you make in the game so interesting. Are they your choices or his? Who would EvilAsh pick: Sayori or Natsuki? Does he deserve to have Yuri kill herself in front of him? A continual tension in the game is the feeling of being in between a dating sim you’ve chosen to play and the choices you yourself make in said sim, and the inner monologue of EvilAsh and the kind of choices he would make. In the second half this becomes particularly intense as EvilAsh doesn’t remember Sayori, but flashbacks of her suicide start popping up. That triangulation is confusing, in and of itself, and Doki exploits it to undermine your sense of control.

Player-Monika

A glib way to look at what happens in the game is that it dissolves into a lot of fourth wall breaking, but that doesn’t really do Monika justice. Sure, there are lots of fourth wall breaks, and sure its ending is one weird direct address/pseudo conversation. However, a fourth wall break usually leaves the wall (its narrative or immersive frame) intact. Deadpool is a good example of this; lots of messing around and wank jokes told directly to the audience, but still a three-act superhero film at the end of the day. Monika, in contrast, re-defines what a wall means by basically just fucking endless bricks at you.

In this, Monika becomes the protagonist, and you as player become the challenge she must overcome. It’s her who wants to win your heart. So within the frame of the Dating Sim is the Player-Monika frame, or more succinctly the “Brick Fucker” frame. The fracture between you as protagonist in the dating sim and Monika as protagonist in her own counter narrative is what fragments the game and our experience of it. It has both a wall, and a japanese schoolgirl taking that wall apart and fucking bricks at you to knock down your wall.

Player-Operating System

To stop the interactive brick experience, you have to delete Monika in the programme files. This contorts our usual sense of immersion. The point of flow and immersion is to make you look past the medium through which you play the game and embed you in the game's world. Instead of this, Doki breaks and extends immersion into your Computer. It’s not that you stop playing the game when you go into the character files; but rather that the game extends past its own window and into your Windows. In this it gamifies a set of skills that are typically functional and boring. Most of the time I use my PC to shuffle and sort files, and not to destroy the fictive existence of schoolgirls I’ve mistreated. That made me really paranoid, as if the game was some kind of honeytrap virus set up by Interpol to catch perverts. Which is to say Windows becomes yet another frame outside of the dating sim or Monika or Evil Ash. In this, Monika hacks into the personal and private frame of your digital life.

Player-Identity

All of this adds up to a deeply introspective experience, one that pushes you to slow down, stop, and reflect. For the first two hours nothing radically strange happens, you just hang out with the girls. That slowness, however, breeds apprehension, as we expect progress in a game. When Monika’s LoveKrafian werk begins, the game steps up these moments of intentional anxiety. For example, when Yuri stabbed herself to death, the game forced me to use the skip function for an unnervingly long time as the text on screen sped by, totally incoherent. Ironically, you can’t “skip” thinking about her suicide.

Sitting quietly with Monika at the end has the same effect. These moments are a kind of forced reflection, which nudge you into thinking about, as Monika has, the frames that shape life and the extent to which we can control them. The strength of this is that it gives the game’s mindfuckery a purpose beyond merely enticing you (see: Death Stranding trailers), confusing you (See: TrumPutin) or entertaining you (See: Deadpool). Doki fucks with your mind to question the banality of our everyday frames, whether they be Kawaii or other cultures, the difficulties of friendship or our dependance on digital mediums and their ephemeral nature. In framing you as guilty and shameful, Doki opens you up to introspection and empathy, experiences that encourage us to look past our habitual frames and to create new ones, like the game’s secret happy ending where Sayori gains consciousness, or gin, or this article you’ve just read