Wot I Think: Digital: A Love Story

Attention-getting top line: right now, I can't think of a better love story in the western medium.

The proviso on that statement is the “right now”. I'm in a jetlagged state, so there's all sorts of things I'm missing – like full control of my limbs, and eyes which see an unblurred world – so I'm not going to give it a GREATEST LOVE STORY EVER WITH KISSES AND HUGS AND FLOWERS AND SPECIAL HOLDING award. But it's a game which I played a couple of weeks back, and has stuck with me ever since. I booted it up right now to take a few screenshots, and felt pangs.

Digital isn't perfect. But it's clever, direct and straight from – and to – the heart. You'll like it a lot.

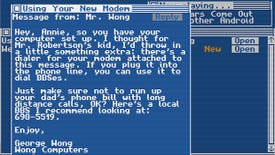

It's the work of one Christine Love and set “five-minutes into the future of 1988” and is basically Uplink reimagined as an adventure rather than a strategy/Elite-esque game. An owner of the fictionalised-Amiga-analogue “Amie”computer – Amiga, of course, famously being Spanish for “Girl friend” - you get gifted a modem and start exploring the Internet of the pre-world-wide-web. You log onto the local bulletin board and find yourself rapidly embroiled in a conspiracy. And with a girl. Mainly, a girl.

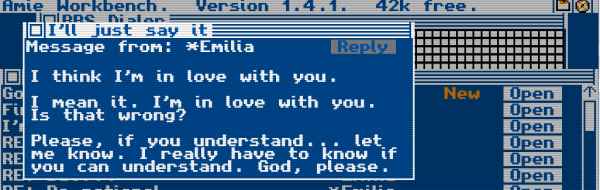

Digital embraces the sort of storytelling mechanics that games are uniquely suited to – by roughly simulating a system that we're aware of, we gain information – and so create an internal narrative – in the same way we would do in real life. So, when logging onto a BBS, you can browse the various exchanges, download programs of questionable legality and mail people. The mailing people is where the game makes the greatest leap of imagination – you simply select “reply” to a mail, which prompts their next mail. Assuming they mail back. You're performing an act of closure. They respond a mail which you, most logically, would have responded with. For example, the opening contact with the lady in question – Emilia – is her posting some poetry on the BBS. You select reply, and she responds with a mail thanking you for the interest, noting no-one ever comments and demands HOT! HOT! CYBER. A/s/l? R u wearing a bra? I am taking off my pants.

There may be a reason why Christine Love wrote this game and I didn't.

The main flaws of the game are related to this system. In the hour-or-so of the game, you'll almost certainly find yourself stuck where you've failed to reply to a mail or a message-board which prompts the next critical step in the story – or, alternatively, failed to download an attachment. It's a system made more onerous by the fact you'll soon be logging into multiple BBSs, and possibly lose track of a key point. In such a situation, where the player is clearly stuck for a long time due to not activating a critical node, it'd perhaps be useful for one of your contacts mail you with a “Interesting post over on the Bruce Sterling's Sexy Armpit BBS!” style mail.

Where it actually succeeds, mechanistically speaking, is in its actual puzzles, which manage to actually evoke a wonderful sense of place. For example, early on you're introduced to toll-avoiding phreaking systems, with numbers being used to circumvent the long distance charges for dialing distant boards. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there's use of codebreakers – but only in a very limited way, with the more awkward boards often being defeated with careful application of knowledge. Much like in the real world – and this is where its atmosphere shines – you'll find yourself scouring boards, looking for an idea of what to try. It simulates research brilliantly – a kind of one-player ARG in the prehistoric days of net-culture. Its totally delightful music and a fine eye for satirical period detail helps a lot too.

The presentation is what sells the prose, which is stripped down, well chosen and elevated by its sheer naturalism. Characters are clear. Even over twenty years on, we recognise these sorts of people. We recognise them from the RPS comments threads. We recognise them in the reflection on our monitor screens. Emilia starts a little idealised, but her iconic minimalism works well – simplify to magnify, simplify to universalise. We imprint on the shape of Emilia, and that imprinted affection is what gives the rest of the game its powerful direction and real mystery.

I'd rather not say any more about the plot's specifics, except you should play it. You can download it from here. It's Wargames about the only two wars that ever really mattered and Neuromancer with tears in the eyes beneath those mirrorshades.