Impressions: The Triumphs And Struggles Of Xenonauts

The alternative aliens

Xenonauts is a spiritual successor to UFO: Enemy Unknown, which means that it’s also a spiritual successor to many of the most tense and glorious hours of my teenage years. Following a successful Kickstarter and a period in Early Access, the game has been available for almost a month now. With its loyal approach to the original design, Xenonauts doesn’t step on XCOM’s toes, but I wondered if it could succesfully muscle in on the original game's territory. Several days of playing later, I have the answer. And some anecdotes about intra-squad romance.

Toshio Ito has a bad feeling. It’s his first time in the field since recruitment and everything is going smoothly but a sense of déjà vu washed over him just now as the downed UFO came into sight. The squad have taken up position, ready to blow seven shades of reconstituted genetic material out of whatever freak opens the door, but Toshio has been told to hang back.

He’s a sharpshooter, a sniper, a death-dealing veteran of two campaigns against brutal insurgents. He’s only killed abstract shapes framed in a scope and with their own crosshair to bear, but he’s seen death up close, ragged and steaming. This is different though. Toshio Ito is afraid. He’s also the first to die.

Melodrama! Turns out Xenonauts brings out the giddy diarist in me just as the UFO: Enemy Unknown did way back when. I used to write what was essentially fan fiction about the lives and deaths of my soldiers, filling in the background of their lives before the invasion and (oh god yes it’s true) lingering on the romances that sprang up between missions. That one guy called with the Guile haircut (Trent Reznor) was totally in love with the new recruit (Billy Corgan), and the mission became personal when Corgan died in the middle of an orchard without a single kill or time unit to his name.

The whole thing became even more creepy when I ran out of celebrity names and started using friends. Then family. When every other barrel o’ names had been scraped to its very bottom, I gave new soldiers the names of my pets. Grizzled veteran Trent Reznor cuddling a gerbil. Dogs lying down with cats, and then making out with the cats one last time as they bled out covered in plasma burns.

(Tangent within a tangent - during quiet moments, usually when hunting down the last alien on a map, couples would occasionally smooch. To do so, they had to spend eight action points, which meant making them kneel in front of one another, and then stand up again. I was too young and naïve to realise I’d inadvertently made it look like they were noshing each other off. Or maybe proposing!)

Hopefully that hasn’t entirely ruined your memories of UFO. The reason I dredge up my own idiosyncratic way of playing is to establish that while Julian Gollop’s masterpiece is an incredibly significant game in my life, the relationship I formed with it isn’t entirely serious. I’m not in awe of UFO and that’s at least partly because it gave me toy soldiers to name and play with when I was a teenager, which inevitably led to the aforementioned melodrama and bad romance.

All of this feeds into my approach to Xenonauts. It’s a spiritual successor to one of the games that caused me to love games but I don’t have any particular expectations as to what it should update, alter or retain. Everyone who has played UFO has their own memories, their own creations within the game and their own false memories about its flaws or lack of. All I wanted from Xenonauts was a game that could stand on its own feet rather than using UFO as a crutch.

It is such a game. I can’t comment on the end-game - potentially the most difficult part to make pleasing for a designer – but Xenonauts has a character of its own and what changes have been made are either improvements or attempts to express that new character. Naturally, it’s the similarities that filled Toshio with such dread.

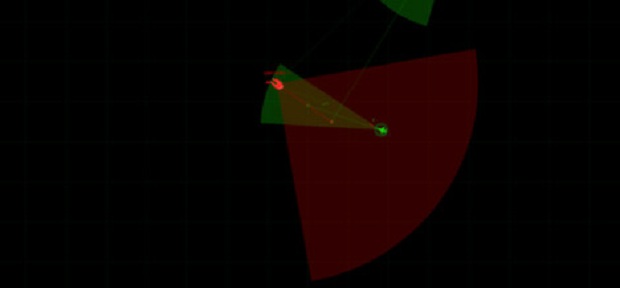

The situation described in that earlier paragraph – the squad forming a perfect perimeter around a downed UFO – is second nature to me. I see the UFO, I order my soldiers to preserve time units for a quick shot, I look for cover that provides a good view of the ship’s door, I move everybody into the correct position. They kneel in the dirt of a rural dustbowl or the icing of an Arctic drift. Everything is set. I’m in control.

And then, during the sinister veil of ‘alien movement’, the shattering of glass, and a sound somewhere between a raygun and a breaking bone. Toshio is dead. He hasn’t fired a shot and he’s dead. I knew it was going to happen sooner or later, this snuffing out of life in an instant, this sundering of plans and protocols. Toshio knew it too. That’s where his déjà vu came from. Xenonauts may be set in 1979 rather than UFO’s future-nineties, but everything is recognisable, from the strategic Geoscape, top-down base design and isometric turn-based combat. The question becomes this – does it have enough differences to justify playing instead of its inspiration? Or, perhaps, is it simply a better game?

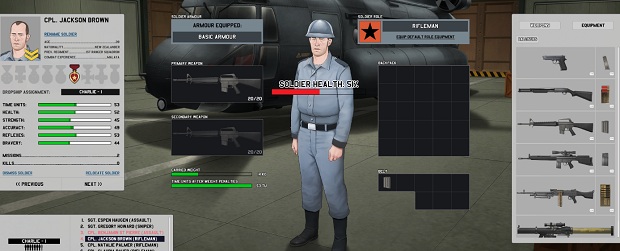

I surprised myself when I realised that my answer to the first question was ‘yes’. Simple things such as the handling of inventories and basic munitions are definite improvements, in my slightly conceited opinion. Occupying a UFO for five turns ends a mission successfully, which prevents one little bastard from hiding in a corner to waste your time. Governments don’t make their last, best line of defence buy basic ammunition and weapons. The Xenonauts are soldiers and they’re ready for war, although not entirely ready for the particular war that engulfs them.

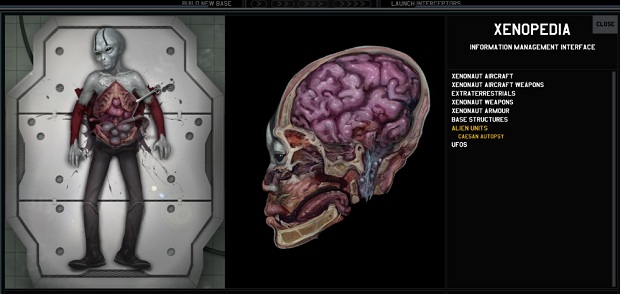

That’s where research comes in, of course, turning the alien’s biology and weaponry against them. Little has changed in base management, research and manufacture, but something important is happening with the data collected. The best way to describe what is possibly my favourite aspect of Xenonauts is to compare it to Firaxis’ XCOM. In that game, the narrative of the invasion is told using a few characters, delivering fully-voiced connections between one ‘stage’ of the game and the next.

The ‘stages’ might be tied to specific missions, progress or research results, but they serve to provide a connective tissue between the strategic long-game and the scattering of tactical missions that make up a campaign. Xenonauts does something similar, although it isn’t obvious at first. Instead of talking heads, Goldhawk’s game constructs its connective tissue with text and illustrations. Xenonauts contains a lot of text and it’s engaging stuff, whether describing an alien’s guts or the reasoning behind an interceptor’s upgrade costs.

It’s the reasoning that grips me. Everything in Xenonauts justifies its place, as if a constant demand of the design document were that elements must contribute to the experience and the fiction at the same time. Some people might find that a small detail to focus on but it’s the kind of fine texturing that explains a lot about the project its contained within. Xenonauts strives for credibility, explaining why an alien behaves as it does, and why refitting a vehicle takes so much time, money and effort. That credibility bleeds through into the characters and I find myself caring for them, as individuals, far more than I do for XCOM’s super-marines.

Perhaps that’s also due to the higher threat level. It’d make sense for the soldiers who stick around longest to have the most impact, but here’s me remembering poor Toshio who basically stumbled out of a helicopter and died with his laces untied. I still remember Cannon Fodder’s Boot Hill with a pang as well, and find Flanders Field more evocative than any tale of derring-do. For all the silliness I indulge in with my intra-squad love triangles, UFO and Xenonauts both successfully make me fear for and invest in the lives of my soldiers.

The visual design of the world bolsters my attachment and on that front Xenonauts succeeds handsomely. Its vehicles, gear and aliens are more realist in appearance than those of its predecessor’s chunky sci-fi comic book world. Additional touches bring the world to life, particularly the presence of ground forces who fight back against the aliens. It never made sense that XCOM were all alone in the fight from moment to moment, and it’s good to see local military and security forces doing their best to help out. Hearing a firefight break out on the other side of a map is usually enough to make me rush my squad into danger, trying to save the poor copper who has ended up trapped in a building surrounded by beasties.

The beasties are perhaps the most disappointing element. They hew too close to the UFO template, which is understandable but does make progression rather more predictable than I’d have liked. Enemy Known. They look great on the slab, sliced open and dissected, but they don’t have the B movie exaggerations of their predecessors out in the field and aren’t quite as fearsome.

Progress through the game is a little predictable but that’s not my biggest complaint. Right now, busy as I am, the main thing preventing me from finishing a campaign is the slow pace. Nu-XCOM rushes along a little too quickly for my liking, escalating like a coulrophobic’s blood pressure during an unexpected John Wayne Gacy fanfest. Xenonauts drags its feet too much, making the track from start to end seem longer than I’d like it to be. To move between one tier of crafts and creatures and the next, it’s often necessary to play several near-identical missions back to back. Maps are randomised but there’s still not quite enough variety in terms of terrain types and features to keep me fully engaged during a long session.

That said, the length of the campaign is precisely what allows the player to apply reactive tactics. When new enemies are introduced, experimental squads can be sent to deal with them. If things don’t quite work out, there’s room to tweak loadouts in order to turn the tables. There’s a much broader and more malleable approach to the structure of squads than in XCOM’s tight skill-driven processes. I’ve even found vehicles extremely useful, having been left unconvinced by every other XCOM game in history. Except, I guess, Interceptor, which convinced me of many things, including the existence of a higher power that hates me (I was 17, earned very little money, and was daft enough to have an allegiance to a franchise - never do that, franchises don't love you like I love you).

Xenonauts is a very good attempt to update and rejig UFO. It can't possibly leave the same impression as the original, on me at least, because it's gracefully planting itself precisely in the impression that the original left behind. As expected, it erases some flaws and exposes others, but it also has enough of a personality to appeal to more than nostalgia. I usually have UFO installed at all times but I haven’t played it for a while and if I do fancy some turn-based alien-trouncing, I’ll stick with Xenonauts for now. And XCOM. They make a rather complementary couple.