From Alpha Centauri To Apocalypse: The Design And Inspirations Behind Frozen Synapse 2

Living cities, killer strategies

Frozen Synapse 2 [official site] is, without a doubt, one of the most exciting games I've ever seen. I've spent a long time considering how best to put my thoughts about it into words, having met with Paul Kilduff-Taylor, composer of lovely electronica and co-founder of Mode 7 Games, to see how development was progressing. The simple fact is, it ticks so many boxes in the 'dream game' column that extreme enthusiasm is entirely appropriate. Here's why.

When I met with Kilduff-Taylor, I had plenty of questions. The reveal of the game's procedural cities had filled my brain with all kinds of ideas regarding how both the short-term tactical combat and the long-term strategies might play out.

Would factions behave as proper entities in the game world, with their own duties and objectives? Would it be possible to zoom into any area in one of the infinite cities and get an impression of its purpose in the grand scheme of things? In short, would the game simulate as much as possible, creating a sense of life and events unfolding, rather than simply providing a randomised canvas for the player to decorate?

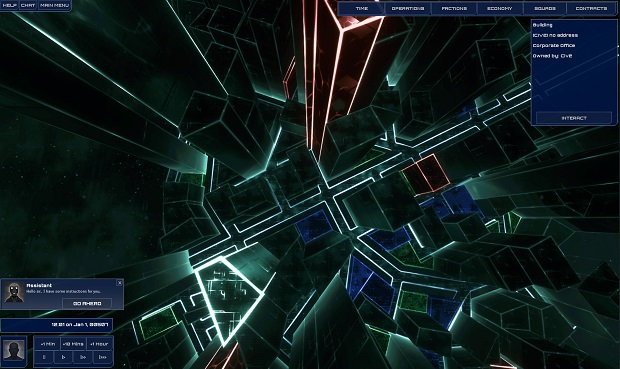

As I was given a guided tour of a pre-generated city (the procedural tools were working but take a great deal of time and are imperfect in this early build), every question I asked met with the response I was hoping for. Emergency services will respond to events when needed, civilians can be caught in the crossfire and buildings aren't just decoration – they have functions and owners.

I've always wanted to see a developer take some of the ideas in X-COM: Apocalypse and run with them. A strategy game set in a living city, with organisations that provide both services and resistance. While Mode 7 acknowledge the influence of MicroProse's hugely ambitious game, Kilduff-Taylor tells me that Alpha Centauri is an even bigger influence, in terms of how factions behave. They have their own ideologies and objectives, and, most importantly, they have agency. They will act as well as reacting.

When the game begins, each faction will have control of an area of the city and they will perform a role within that zone. The catalyst for the events that kick off the strategic struggle is a series of incursions by a force as yet unknown. They might strike at an area controlled by the player or they might strike at an AI faction. Either way, their efforts will cause the shape of the city to change as they gain power and drive organisations to desperate survival measures.

Control doesn't involve simply owning areas of the map though. Kilduff-Taylor talks about 'painting the map' in a pejorative way. You're not trying to cover the whole city in your colour through direct conquest, instead you'll be identifying useful resources or locations and attempting to ease access to those things using brute force or misdirection.

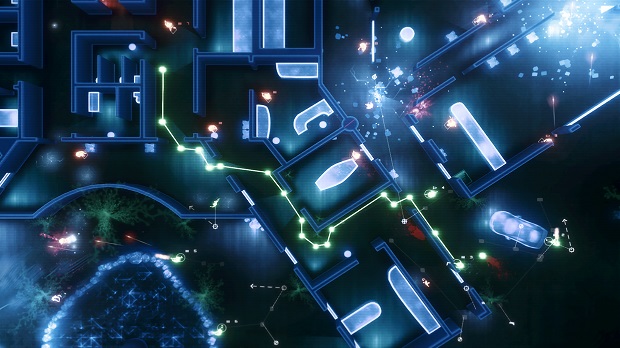

A simple example plays out. We need money so we storm a bank. It'd be possible to use stealth, performing a careful heist, but this time the squad goes in all guns blazing. Even so, there are a few ticks of quiet tension as our infiltrators move into position. As soon as the guards spot them, they respond, but not in the way you might expect.

Rather than returning fire and calling for backup, causing every unit on the map to zero in on the attacking squad's position, the guards use their artificial brains to figure out what's actually important. What should they be doing right now?

Engaging in a shoot-out on the bank's periphery, in a lobby, doesn't seem like a particularly smart use of their lives, so they set up defensive perimeters around the vaults and other items of interest instead. They take a good guess as to why your squad might be attacking the bank in the first place – to steal cash or important data hidden in secure deposit boxes – and they react accordingly.

The encounter plays out using the rules of engagement laid out in the original Frozen Synapse. You give orders and then advance time to watch those orders play out as the AI acts simultaneously. In this particular version of events, a guard fumbles a smoke grenade and ends up lost in the clouds, while our squad make their way into the building, killing as they go.

There will be gas grenades as well as smoke grenades and seeing them in action is a reminder of how elegant the game's aesthetics can be. The gas forms a circle around the explosion but that circle will deform as it hits walls, trees and other objects in the environment. It looks like a fluid, spreading and reshaping itself around obstacles.

The biggest change from the original game, in terms of the tactical combat, is in the early stages of each encounter. Rather than starting in media res, with combat the only option, you'll have time to scout out the building and enemy patrol routes. The vehicle that your squad arrives in is customisable, which began as an aesthetic choice but became an important mechanic. Because you'll be arriving at street level, with little cover in sight, the design of the vehicle will allow you to create cover for your squad, ensuring they're not completely exposed.

You'll be able to use all manner of loadouts to get the job done, whatever the job might be on any particular mission. Squads are made up of units based on 'vatforms'. You buy the rights to a form and can then replicate it whenever the current version perishes. That means there's no permadeath – once you've bought the rights to an individual, you can recreate that same person, with a persistent portrait and stats, at will.

Kilduff-Taylor admits that something is lost in terms of emotional attachment when units are effectively immortal but the fact that the same characters will be accompanying you through an entire campaign should create a different kind of attachment. You might not be afraid of losing them but they'll be involved in plenty of stories, allowing you to impose plenty of character traits on them should you so desire.

The battle for the city isn't fought with guns and vatformed soldiers alone though. Frozen Synapse 2 is a game about control of information.

When you click on a faction on the map screen, you can talk to them and declare your intentions or try to smooth over any recent 'misunderstandings'. Deeper than that though, Mode 7 are considering systems that will allow you to intercept communications between factions – that might be a way to learn about movement of squads, the strength of incursions or the location of important resources.

Clicking on a building opens up a different interface, showing everything you know about the factions that are likely to be present there and any objects or information that you might be able to steal or otherwise secure. If you choose to send a squad to the building, the game will identify objectives based on what is present in the scene. An enemy faction is holed up there? You can choose to assault the building. A vault full of cash? You can try to pull off a heist.

But you might simply want to loiter, exerting pressure. When you arrive at the scene – and squads will physically move around the map and can even encounter one another en route to a building at which point the game will generate a map based on the street where you meet for combat purposes – you can leave your soldiers outside, encouraging the controlling faction to react rather than initiating contact. You could even call them, laying out a list of demands.

Just as they'll react believably within the tactical mission spaces, factions will make moves on the strategic map. As well as moving their squads around the city, they can issue contracts. If they want to get something done but don't have the tools or standing to do it themselves, a contract will be listed and another faction might pick it up, forming a temporary alliance. The interplay between AI entities should lead to a convincingly dynamic environment, all undercut by the incursions from outside that threaten everyone.

Both layers of the game, the tactical and the strategic, are driven by intelligent systems that don't just simulate behaviour but encourage participation. Ideally, you'll be able to nudge a particular faction and see a convincing response – whether it's the hunkering down of a militarised faction or the violent onslaught of vicious cult – and then you'll be forced to react to the AI when it pushes back.

There's an enormous amount of work to be done but there's a sense of calm around development. Even as I was showing signs of astonishment at the scope of the simulation, Kilduff-Taylor insisted that every element of the game sensibly led into the next.

“We weren't sure that stealth would work, but it does – it worked right away, in fact - so that's good. Frozen Cortex was very important because it forms the middle-ground between the two Synapse games. It was the point when we realised that introducing stats for units didn't upset the simplicity, and that it became a sort of metagame in and of itself.

“We're moving away from the blocky buildings of the first game. There are curved walls, trees, cars that you can vault over. We're implementing parks and outdoor areas as well, with water and rocks, and mabe even tunnel networks. It's all a case of adding to a foundation that has already been tested though. We didn't know Frozen Synapse would become something so big but as soon as we realised it could...

“There are still things that we're not sure about. You might be able to steal data that gives you information about a faction’s plans, for instance, but we don't know how valuable information will be until we've put it in the hands of players. We need to know how useful it is before we decide what to conceal and what to reveal.”

Speaking of his colleague and Mode 7 co-founded Ian Hardingham, who is handling most of the coding single-handedly though with some freelance support, Kilduff-Taylor describes him as “a very particular sort of programmer. That's what it takes to build something like this.” I get the sense that the level of trust and awareness of those particular qualities runs both ways – this is a big game that perhaps necessarily had to be made by a small studio, with a detailed knowledge of their own capabilities. In person, I get the paradoxical sense that this most ambitious of games isn't actually that much of a stretch at all.

“It's a very complex game. And that's fine. It works. It's all fine.”