IF Only: dressed for the party

costumes and disguises

Plundered Hearts (Amy Briggs/Infocom, 1987) was Infocom's one and only romance. It was also very much ahead of its time. Emulating the conventions of romance meant offering richer non-player characters, and spending more interaction time with them. There was a definite plot, not just a sequence of puzzles in an underpopulated landscape. There were set scenes where you could be clever and turn the tables on your enemies. There were multiple possible endings, depending on whether you wanted to give your heart to the sexy pirate after all.

Not only that, but it was easy enough to complete, even before we all knew how to find walkthroughs on the internet. When I got to Plundered Hearts as a teenager, I'd been playing Infocom and Scott Adams games since the age of six, without ever seeing the end of a single one. This was the first text adventure I ever actually finished.

Most of all, Plundered Hearts won my heart when I first played it because it let me enact a few favorite fantasies, from escaping a pirate ship to discovering secret tunnels to turning up at a ball in a gorgeous ivory silk gown.

I'd played other games where the gameplay required a disguise. But I'd rarely played any with puzzles about fitting in socially or meeting a dress code. And to some extent, the dress-up scene I loved was just a symbolic stand-in for something deeper that I was unconsciously looking for then and have been more intentionally seeking ever since: gameplay that spoke as much about interpersonal dynamics as about physics or combat.

If you also would enjoy dressing up for a ball and possibly doing a bit of swashbucklery, here are some other suggestions:

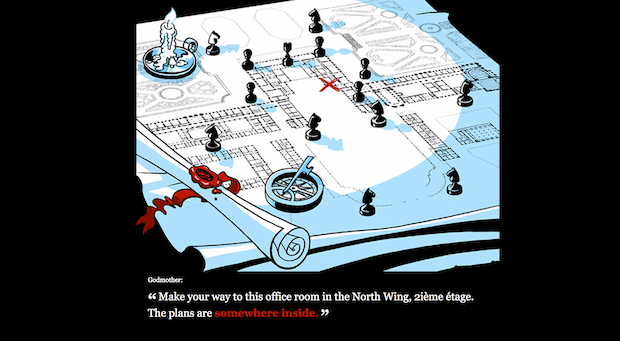

Secret Agent Cinder by Emily Ryan (Twine, 2015) is a beautifully illustrated and polished piece that remixes Cinderella with the French Revolution. You are a daring agent of the People, sneaking into Versailles in order to take out your aristocratic enemies. You need to be appropriately geared and dressed for the part. The guards are an impediment. The Prince is an idiot.

There's a lot to love about Secret Agent Cinder. The illustrations are stylish, and form an integral part of the gameplay. (A number of them contain their own little jokes, too, separate from what's in the text.)

But my favorite moment involves dressing Cinder for her mission, where the author is playing on RPG gear selection.

Be careful. If you don't watch out, you will wind up in the Bastille. For all its stylish accessibility, Secret Agent Cinder is not completely easy. The game is a puzzle that can lead to several possible outcomes; you may well need to try several times in order to win, or to improve your outcome once you've survived the first time.

Masquerade (parser, Inform, 2000) is set in slightly less elevated society, a world of 19th century small-town Americana. The protagonist's father has put their financial future at risk, and it's up to Amelia to try to sort things out. No one particularly wants to take her seriously, though, because she's female. She has to dress up, down, or as a man, as needed.

There is a hero available to help save the day, but one of the things I like about Masquerade is that the romance is not mandatory. You can go along with him or not, and either way, the heroine is allowed the possibility of a happy future. Indeed, the whole point of Masquerade is that the heroine earns her right to control her own future; and she does it in part by learning to manipulate, overcome, or work around the social strictures that define what she is supposed to do. If the game forced Amelia to end up with her suitor at the end, it would undermine the whole point of the story.

Masquerade has a companion piece, The Cove, which shows the same protagonist in a more contemplative mode, and sketches in some of her backstory.

S. Woodson's Magical Makeover (Twine, 2014) is a parodic riff on pink-shaded girl games. You're making yourself up for a party where you feel a bit socially inferior to the others who will be there. Use any of the several magical care products described, and you'll find yourself transformed in extraordinary ways.

It's an unconventionally-shaped story, because your initial choice of cosmetics makes a huge difference to what comes next. Once you've made up your mind, though, you're on one of several fairly linear tracks, and the narrative branches much less. Sam Ashwell's choice-based-game structures glossary refers to this as a Sorting Hat structure, where your fate is totally determined by an early decision. In general I tend to think this isn't a great design choice, but it works in Magical Makeover for three reasons.

One: the individual storylines that come out of that choice point are all well-written and funny, even if they don't allow very much additional agency.

Two: it's worth reading all of them. Things that happen in one story may be explained by the contents of another; it might even be reasonable to think of these as elements of a tightly knit anthology.

Three: the mechanic here beautifully underscores the satire. Once I encountered an ad for eyeshadow primer where the protagonist tried to flirt with a man at a party, but the clumped eyeshadow in her lid-crease disgusted him so much that he rejected her. I've never had anything remotely like that happen to me in real life: barring professional photo shoots, usually anyone in a position to critique your eyeshadow coverage must already be pretty into you. But in Magical Makeover, your choice of exfoliant really does matter as much as the ads imply.

Honorable mentions: Party Foul (Brooks Reeves, parser, Inform, 2010) is a puzzle game with an escape theme, in which you're at a cocktail party you'd really rather get away from. The setting is very much suburban middle America, with middle-aged people getting sloppily drunk and watching football, and your outfit is unsentimentally described; but this, too, is a game about managing social situations. The non-player characters are mostly not particularly likable (which is the point).

Dial C for Cupcakes (Ryan Veeder, parser, Inform, 2014) puts you at a Halloween costume party with the aim of collecting all the different cupcake flavors you can. There's a little more of a frame story than that, but really, it's pretty much an excuse to vividly describe baked goods.

[Disclosures: Emily has not to the best of her knowledge met any of the authors whose work is covered here. She has appeared on Ryan Veeder's podcast Clash of the Type-ins. More generally, Emily Short is not a journalist by trade and works professionally with various interactive fiction publishers. You can find out more about her commercial affiliations at her website.]