The rise and rise of .io games

The browser game reborn

19-year-old Brazilian developer Matheus Valadares announced his game Agar.io on 4chan on April 27th 2015. Within weeks it had been picked up by free online games site Miniclip, as well as popular Twitch streamers and YouTubers. In a May 2015 video with 8.2 million views, PewDiePie called it his “new favourite game,” and he subsequently covered it at least nine more times.

Agar.io quickly became so popular that a genre was born. Despite not having any formal connection, the “.io” domain extension has become synonymous with an extremely popular segment of browser multiplayer games, characterised by simple graphics and player vs. player mechanics.

Agar.io’s mechanics had appeared in games such as Osmos before: players compete to become the largest cell in a petri dish playing field by eating smaller cells, including other players, while avoiding being eaten themselves. But Osmos, though popular and critically acclaimed, did not go viral. Agar.io did.

The influence of massive video creators on the popularity of .io games can hardly be understated, but in his video PewDiePie is clear that his fans had been clamouring for his coverage of Agar.io for some time. The game had already become a success by spreading through social media and word of mouth.

Much of this popularity was down to its accessibility. On pretty much any computer with an internet connection, anyone can jump into a game for free, within seconds, and understand its mechanics. Yet it’s tricky to master, making it easy to get caught up in a loop of “one more try.”

Players are also given the opportunity to customise their cell’s name and skin; giving matches a sense of story. “REDDIT WANTS TO EAT ME!” crows the title of PewDiePie’s first video, riffing off the fact that he was chased by a huge cell sporting the website’s logo. In the summer of 2015, this led to the game becoming one of the fronts on which the highly contested Turkish elections were fought. Political parties released posters showing cells with their names on them “eating” the 10% vote threshold that they needed to exceed for parliamentary representation. In-game, players could be found with names referencing these same political tensions, teaming up or chasing one depending on their allegiances.

It was also this customisability that demonstrated how quickly Agar.io had exploded from its original 4chan-based target audience. Some skins clearly reflected the harmful “humour” of the communities who were first introduced to the game. For example, the game originally gave players the option of calling themselves “Nazi,” which would give their cell a swastika skin. When a Reddit user pointed out that this imagery is illegal in Germany and that the game should block users with a German IP address from seeing the skin, Valadares (known as Zeach on Reddit) responded with a hard “no.”

But it was Agar.io’s mass appeal that had hooked in Miniclip, not its pandering to niche online communities. Two weeks later, the Nazi skin was made unavailable and unviewable in countries where it was illegal, and a month after that it was removed entirely. Not everyone was pleased: the top Reddit comment following these changes reads “We want pepe for compensation,” referencing a meme that grew in popularity on 4chan (among other websites), and would soon be coopted by white supremacists. Others clearly felt that the ability to masquerade as a swastika was part of the appeal of the game, claiming that despite its accessibility, Agar.io wasn’t “for the weak.” Pepe was never added, but some of the influences of that original audience can still be seen. Skins like the confederate flag remain, and from my testing with slurs that I have the questionable pleasure of reclaiming, there doesn’t seem to be any kind of nickname regulation.

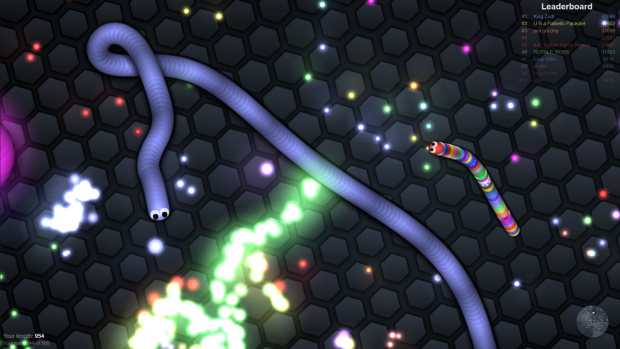

Nonetheless, Agar.io had opened a market, and developers began to iterate on its premise. The next huge hit was Slither.io, released in March 2016, which adds a Snake-like twist to the mechanics. Players are worms rather than cells, and must avoid touching other players head-on while collecting orbs to grow. There’s still an element of ruthlessness – players burst into orbs when killed, so forcing a player to crash into you is a good way to grow fast. This also means that smaller players can feel the rush of destroying a much larger worm.

Slither.io brought the same perfect storm of low-commitment, die-and-retry gameplay; eye-catching and customisable visuals; and attention from YouTubers and Twitch streamers, and became even bigger than its predecessor, with 68 million app downloads and 67 million plays in browser within three months.

But it was only one of hundreds of similar games released after Agar.io became a sensation. Two of the most popular, Zombs.io and Spinz.io, both made by Yang Liu, demonstrate the ways in which the genre has changed – and stayed the same.

Liu and his team decided to try their hand at making .io games in 2017. “Despite Agar.io having come out two years prior, we felt that there was potential for innovation in the space,” he told me. “What attracted us to these games is the low barrier to entry for players and the social mechanics that are rarely found elsewhere.”

Liu emphasised that what he finds most interesting about .io games is the real-time interaction with other players. “Essentially, you’re actively employing game theory strategies while playing. You’re thinking “is this guy next to me going to be rational in his decision making? Or is he going to do something stupid and cause mutual destruction?””

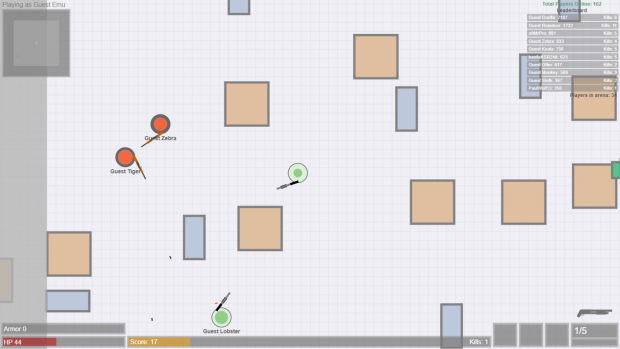

The team first tried a version with shooting mechanics called LASERSHARKS.io. “It didn’t do so well,” Liu told me bluntly. But with their understanding of the tech in place, Liu’s team wanted to try something more in-depth. “I felt this type of gameplay had a lot of room to grow. Something with Zombs’ complexity hasn’t been done in the .io game space before just due to it being real-time, persistent, and massively multiplayer.”

He attributes Zombs.io’s success to these new aspects and how they interact with the inherent multiplayer attraction of .io games. “Tower defense and base building games have also been out long before Zombs.io, however Zombs.io adds that social element where people can interact in real-time, and more importantly, in a persistent world. Combining the real-time interactions…and the mechanics of tower defense games into one game allowed players to have a new type of massive multiplayer .io game experience.”

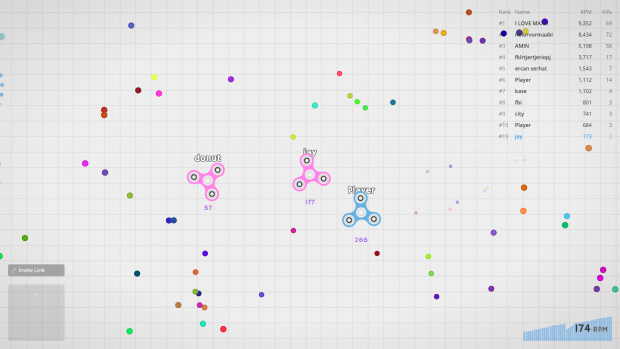

So why make Spinz.io, which adheres much more closely to Agar.io’s playstyle, but with fidget spinners rather than cells? “The week after we made Zombs.io, we were super ecstatic that it hit a million users in a week, but we were still bummed that we weren’t able to pull off a “typical .io game hit” with Lasersharks. So since fidget spinners were popular, we wanted to make something that “PewDiePie would play on stream.” We still don’t know what that is exactly, but it happened and Spinz.io took off.”

Wes, the developer of shooting-based .io game Gats.io told me that “[.io game] developers don’t really need to come up with original ideas [to be successful],”. Yet he and his team aimed “to recreate the Call of Duty/Battlefield experience as a 2D MMO.” Melvin, developer of the Pictionary-style Skribbl.io said that he deviated from the Agar.io formula because he felt that “getting bigger” .io games were “overdone.” It’s thanks to developers like these that the domain has become a catch-all term for easy to jump into browser multiplayer games that often have little in common mechanically or thematically.

“.io” is technically the country code for the British Indian Ocean Territory, a cluster of over a thousand islands situated between Tanzania and Indonesia. Once home to over 2,000 indigenous Chagossians, they were forcibly removed by the British to make way for a US military base, ironically named Camp Justice.

Being that the archipelago’s inhabitants are now entirely American or British, the extension is rarely if ever used for local sites, and is therefore treated by Google as a generic top level domain. This is good for sites’ search rankings, and its relative lack of popularity means that many more names are available than under .com or similar extensions. These initial factors combine with the fact that it has now become a recognisable shorthand for games that, as Melvin put it “let the player join a game immediately without a hiccup,” and mean that it’s “better publicity” for developers to conform to the genre convention.

But Skribbl.io shares one other similarity with Agar.io – a total lack of moderation. Its homepage carries a disclaimer: “The owner of this site is not responsible for any user generated content (drawings, messages, usernames).” That content is routinely abusive and hateful, as well as NSFW (the game makes no attempt at establishing an age gate). Melvin did not respond to my request for comment about this problem.

.io games’ popularity doesn’t seem likely to wane any time soon, with developers merging into new formats like Zombs.io, and capitalising on new trends like in Spinz.io. Despite some games being held back by the same issues that betrayed Agar.io’s chan-based origins, the genre has become a hugely disparate group of games held together by their ease of access, multiplayer foundations, and a domain name. And for as long as this popularity holds, developers will continue to iterate, both with new memes and new mechanics, keeping this reinvigoration of browser multiplayer games going.