Life Is Strange: Before The Storm can't escape the first game's use of harmful tropes

The inevitability of "Bury Your Gays"

Spoiler warning: This article includes spoilers for the entirety of both Life Is Strange and Life Is Strange: Before The Storm.

Life Is Strange: Before The Storm is, in its own right, a very good game. But it can’t avoid the fact that it’s a Life Is Strange game, specifically a prequel to the original. And in the original, one of its central characters is dead.

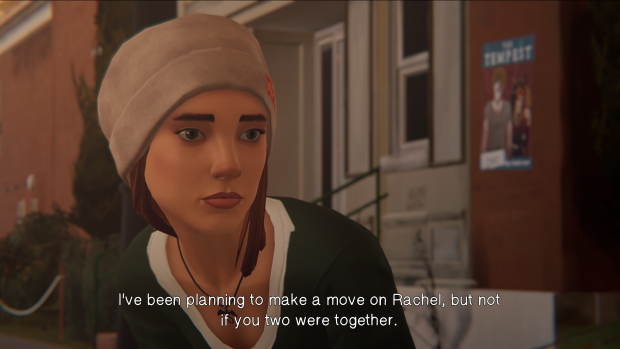

Before The Storm focuses on the relationship between Rachel Amber and Chloe Price. The first Life Is Strange focuses on Rachel’s disappearance. The fact that she was murdered isn’t revealed until the fourth episode, meaning fans had plenty of time to speculate about her: who she was; how she and Chloe felt about each other; and when she would return, alive.

But Rachel did not return. Instead, we were given a scene of Chloe sobbing over the body of the woman she loved; the first time that Life Is Strange leaned on the trope, known as Bury Your Gays, in which gay and lesbian characters are denied a happy ending. The problem with this trope hinges on two facts: there are relatively few LGBTQ+ characters in media, and those that do exist are disproportionately likely to end up dead. Taken together, they gives the impression that LGBTQ+ people (especially queer women) and their relationships are doomed to end in tragedy.

When it comes to Life Is Strange, Rachel’s death was largely overshadowed by the game’s second use of the trope: its ending. The player is asked whether they want to save Chloe, resulting in a storm wiping out the town of Arcadia Bay, or whether they want to save the town but sacrifice Chloe in the process.

Neither is a happy ending for Max and Chloe, and this is exacerbated by the fact that they only kiss in the “sacrifice Chloe” ending, as well as the fact that Dontnod seem to position this choice as the “correct” option. It’s given a much longer ending cutscene that revisits all the major characters – though you have to watch Chloe die alone on a bathroom floor first. The other ending cutscene shows Max and Chloe leaving Arcadia Bay, but gives no indication what they do after that.

Before The Storm only exists in this context: a follow up to a game that appealed to queer women in a way that few games even try to, but that had left many feeling disappointed through its use of harmful tropes. Once Deck Nine and Square Enix decided to make a prequel focusing on Rachel and Chloe, their already fraught position became even trickier to navigate, because, as far as the audience was concerned, Rachel was already dead.

Deck Nine did an admirable job in telling Chloe and Rachel’s story. Their exploration of the women’s relationship is, in many ways, better told than that of Max and Chloe, not least because the latter’s feelings are left more open to player choice and interpretation. It is an altogether better story about queer young people falling in love, and a better overall game for it.

Or it would be, if it weren’t for the elephant in the room for its entirety. When Rachel and Chloe talk about escaping their lives and moving to California together, as they do often, it’s not the hopeful (or perhaps fanciful) conversation that it should be. It’s tragic, because we know that it can’t happen. When bad things happen to them, it just feels unfair because we already know that they suffer enough. When they’re happy, it’s only a reminder that it will be all too fleeting.

Such are the constraints of a prequel, and the fact that Rachel dies doesn’t mean that we can’t explore her life. Almost all of Before The Storm avoids drawing attention to Rachel’s ultimate end, allowing players to become invested in her if they can personally overlook it.

But after the credits roll, a brief cutscene plays. In the first half, Chloe and Rachel are joking around in a photo booth. They look happy. At one point, Rachel kisses Chloe on the cheek. This is then juxtaposed with a shot of Rachel’s phone. Chloe is calling; she’s called seventeen times and Rachel hasn’t picked up. She can’t pick up, because in the background we hear her being abused by Mark Jefferson, in the lead up to her death.

This scene isn’t only wildly unnecessary, it’s profoundly cruel. It plays like a Marvel cinematic universe tease, as though we are supposed to get excited for the brutal murder of yet another queer female character. But we already know what happens; the scene has no purpose beyond being a gut-wrenching reminder that, yet again, the same-gender couple does not get a happy ending.

As if fans had ever forgotten, especially queer fans who see this sort of tragedy play out all too often in the rare times that they see themselves on screen at all. Many fans put that fact aside to become invested in Rachel and Chloe, not least because they don’t have many alternatives when it comes to representation. And the final seconds of the game threw away their good faith for the sake of cheap shock.

Moreover, Life Is Strange is supposed to be choice based. The first game’s binary choice ending erases most of the other choices the player has made regardless of which way they go; Before The Storm offers no choice at all. Even Farewell, Before The Storm’s bonus episode, has a fixed end of Chloe grieving her father’s death, lying on the floor in a way that is strongly reminiscent of her death scene. Breaking from the series' previous mechanics like this implies inevitability, as though these women were doomed no matter what they did.

It’s an extra layer to the inevitability LGBTQ+ fans already feel when yet another piece of media uses the Bury Your Gays trope. Before The Storm could not avoid the context of this wider problem, neither could it avoid the fact that Rachel Amber dies after its credits roll. But it did not have to lean into that fact. Its post-credits stinger offered nothing but a tired retelling of the same story that its predecessor and so much other media gives to queer fans, undermining the otherwise good representation of relatable, endearing young women in love.