The art of the pause

Time crisis

Hitting pause in a video game is like dropping a wall across it. On one side of the wall lies what is called the diegetic space of the game, aka the fictitious world, which is generally the aspect that receives the most interest, the aspect that tends to attract the weasel word "immersive". On the other side of the wall lie menus, settings and other features that form a non-diegetic layer of bald operator functions - technical conveniences and lists of things to tweak or customise, from graphics modes to character inventory, that are cut adrift in a vacuum outside of time.

In theory, the pause screen and its contents are not truly part of the game. There is no temporality, no sense of place, no threat, no possibility of play, no character or narrative, no save the princess, no press X to Jason or pay respects, no gather your party before travelling forth. As the scholar Madison Schmalzer points out in the paper I'm wonkily paraphrasing here, "the language of the menu itself emphasizes the menu's position as outside of gameplay by labeling the option to continue as 'resume game.' The game world is always privileged as the site that gameplay happens."

The diegetic/non-diegetic division is blurry, however - indeed, it's fundamentally a lie. As Madison goes on, a game world and a set of pause screen menus are both essentially interfaces for a set of hidden databases. The pause screen is simply the part of the game that renders this more obvious, though it might dress up the process by means of curly fonts and gold trimmings on your UIs, or what have you. And in practice, many games that simulate "real time" are played as much at the level of the pause screen as within the world - speedrunners, in particular, are adept at exploiting pause functionality to fox the simulation. What's more, which features exactly a developer lets you access in real or pause time can make a fascinating indexing of the game's overall design.

Let's compare two cult hits from the past year - handsome fast travel simulator Starfield and indie barrel-management tool Baldur's Gate 3. In Baldur's Gate 3, opening an inventory doesn't pause the game, partly because as a game with turn-based combat, it's under less pressure to slow things down for the player. The game world persists behind that thicket of coloured icons, ticking away quietly alongside the process of searching for that one new sword you want versus the 12 similarly-shaped blades you acquired 20 hours ago and the approximately one hundred lorebooks you can't bear to part with.

It's easy to forget that anything you do in that teeming inventory has an immediate result "inside" the world, and this is the basis for some funny mishaps. You can absent-mindedly discard a lit candle and set an entire room on fire, for example, and this is entirely in keeping with Larian's "yep, we thought of that too" approach to adapting D&D.

In Starfield, inventories are managed in pause time, because Starfield has real-time combat: there's the hotkey menu, yes, but given just how many flavours of item the game offers up, being able to freeze time and organise the glut is all but essential. This sounds like a dreary capitulation to convenience, and the business of zipping between nested menus is tiresome in itself. On the whole, I think Starfield is a step backward in terms of the real/pause time distinction from Bethesda's Fallout games, with their freeze-frame VATS mode targeting systems. But it does enable a familiar form of distinctly Bethesda-brand sorcery, such as "summoning" 20 objects in a split second, or engulfing an entire banquet of healing items just before a fatal enemy bullet makes contact.

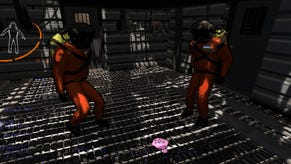

Most of my shoot-outs in Starfield are punctuated by the act of projectile-vomiting spare dozens of SMGs and space helmets while simultaneously downing a cocktail of freeze-dried apple pie, stolen moonshine and xenobiological performance enhancers. It must be absolutely terrifying to witness, and it lends an invigorating silliness to an RPG that can be painfully earnest about situating itself as the one true video game heir to NASA.

It's not a PC game - I will perform the requisite penitence later, once I've got my flail back from the cleaners - but I do have to mention the latest Zelda game here. In Tears of the Kingdom, you get a bunch of abilities that can be defined in terms of how they work with or interrupt the flow of time. Using Fuse to combine inventory items into fancy breeds of arrow pauses the game. This seems necessary because Tears of the Kingdom gives you almost as many items as Baldur's Gate 3, and its inventories are accordingly a frightful jumble. Ultrahand, the game's vehicle-editing tool, operates in real time. This trades the ease-of-use of a "proper" editing screen for the comedy of designing a monstrous six-wheel mechatank while subject to Zelda's boisterous physics. It's amusing, but with a definite cost in the shape of making life harder for players with specific accessibility needs.

The final layer of all this I want to touch on today is the relationship between pausing the game and questions of monetisation and copyright. There's a curious strain of antagonism within games publishing for pause screens, which can be traced back across decades. Dedicated pause buttons on controllers came in as part of gaming's move from the arcades to living rooms - coin-op machines seldom allow you to pause, for obvious reasons. In the past 15 years or so, the insistence of many publishers on always-online functionality has made pausing feel like a forgotten luxury. Sometimes it's thrilling that you can't pause, as in Elden Ring (though the trick to From's worlds is realising that they have minimal capacity to move against you, with relatively little in the way of roaming enemies). And sometimes, it's aggravating. In the case of always-online DRM, it's a reminder that the industry doesn't trust you with control of your own time.