Retro: Tales Of The Unknown: The Bard's Tale

[The original version of this appeared in PC Gamer. There's been a handful of additions.]

Maths was always our favourite lesson, for the simple reason we never did any Maths in it. There were always more obvious rebels for the teacher to whip into line than David Hyland, Simon Holmes and myself, crouched over our desks and using the class’ infinite supply of squared paper to copy out each others maps. From a distance, it even looked as if we were working.

The Bard’s Tale wasn’t the first computer role-playing game by any measure, but its conversion-from-DOS was the first any of us had actually played. The previous Spectrum fantasy games were grown from first principles of what a videogames should be, with D&D as an indirect influence. Conversely, following on from Ultima and Wizardry, Bard’s Tale was an attempt to – basically – be Dungeons and Dragons on a home computer. It was a particularly American desire, it seemed. When I was interviewing assorted developers about D&D's influence, Big Huge Games captured the zeitgeist elegantly: "Back in those days I’d say the holy grail of teenager boys learning how to program was to figure out how to ‘make the computer play D&D’. Because if we could do that, what else would we ever need?”.

Even if us Britkids didn't seem to actually do it as much, we were hungry for it, and had the graph-paper to prove it.

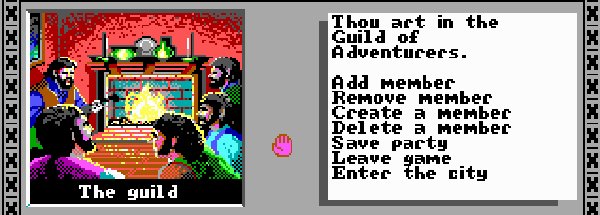

The plot was archetypal: the city of Skara Brae has been isolated in eternal winter by the Archmage Mangar! Stop him! The characters were archetypes: any six selected from a list of Warriors, Paladins, Magicians, Conjurers, Rogues, the eponymous Bard and so on. The settings were archetypal: Sewers, Cellars, Castles, Towers and Catacombs. But the mapping? Unautoed.

This is where things differed back in the eighties. While much of The Bard’s Tale’s constituents would be familiar to a modern gamer, this is a world before the joy of either overhead views or automaps. To have a clue where you were, you resorted to scrawling on squared paper.

In fact, people seemed to think this now-lost art was actually a core part of the game. Take Bard's Tale's sequel which describes its new wilderness areas as "a mapping challenge never before seen in a fantasy game, and a whole new way to get lost”. Christ. It wasn’t as bad as it could have been. While viewed from the first-person, this wasn’t a true scrolling 3D environment. You pressed forward, and your trundles an entire square forward. Play comprised of taking a step forward, pausing, carefully noting with a few pencil marks the walls and then progressing, occasionally interrupted by traps, fisticuffs or trips back up to the city to heal and recharge spell-points. Our Maths lessons-sans-Maths were all about collating everyone’s work. Which could go awry: our map for the first level of the Catacombs stretched across three textbooks before we realised that the dungeon loops every 22 squares.

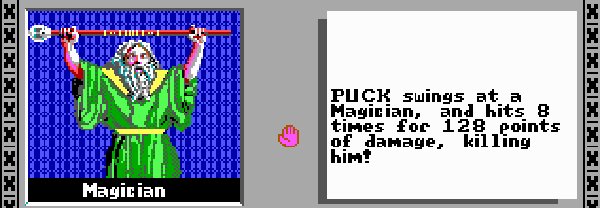

I never completed Bard’s Tale. The “play” key of my Spectrum +2 snapped off when I was wrestling with the multiload, leaving Hyland and Holmes to rush ahead in the three weeks it took to be fixed. Holmes got tied-up battling in Harkyn’s Castle, stuck in an attempt to grind the 396 Berserkers (When you faced off against enemies in Bard’s Tale, it arranged them into four groups. At low levels it may be “You face death itself in the form of… a Halfling”. As you progress, you get things like “You face death itself in the form of… 5 gnomes, 4 orcs, 3 magicians and a Wild Dog” which does make you suspect Magnar must be the proverbial charming motherfucker to get all these diverse personages to join beneath his banner. But its all low double-digits figures until you open a certain door in Harkyn’s and get the ominous message “You face death itself in the form of… 99 berserkers, 99 berserkers, 99 berserkers and 99 berserkers”. Erk!) Only Hyland persisted to the final confrontation with Mangar, where he discovered the game really hadn’t bothered with a proper end-sequence.

They say you can never go back. Tell that to the abandonware folk. With their help, I booked a one way ticket to Skara Brae to see how time has treated this particular blighted city. You go back to games like this with a certain knowledge. Firstly, strategy games – especially turn based games like The Bard’s Tale – tend to age better than their action-based brethren. An RPG now is an RPG then, so those skills of perfecting character builds and equipping people with the right armour or weapons, practiced in every role-playing game since, move directly into play.

Which makes the bits where they were clearly learning how to actually make a role-playing game work stick out like a Thief who’s forgot to take any stealth skills. Take how it treats death. When someone dies, unless you’re willing to pay the (unfeasibly enormous for a beginning character) fee to raise them from the dead, they’re dead. You can’t reload a previous game to recover. It’s Nethack-style hardcore play. Except, after setting the game up like this, the manual actively goes out of the way to advise you how to work around it by backing up your character files or just turning off your PC when a party member has died before it saves their dead state. They knew something was a bad idea, but couldn’t see that was a reason not to include it - presumably it was because of the aforementioned deification of D&D. D&D has permadeath and tricky inacessible resurrection? That's how we have to do it.

It's an odd experience. After a worryingly short period of time, Skara Brae gets beneath my fingertips. I had most of the city memorised, and the muscle memory is still there. Soon I’m running from the guild to the central temples to the magical recharge-shop to the Review Board with barely a glance at the screen. Stepping into the Catacombs (The Mad God’s Name is “Tarjan”, twenty-years out of date Spoiler fans) I effortlessly locate the room featuring 9 Wights which I used as an early grinding run, relying on my bard blowing his area-effect Fire Horn before they tore us to pieces, for about 1500XP a pop. How can I remember all this when I don’t remember the name of 95% of my classmates? But since it’s a fledgling prototype of the modern RPG, there’s little which hasn’t been seen in more advanced games. While an interesting historical exercise, it fails on the ultimate test: which is “Is there a reason to play it now”?

Well, it would, if it wasn’t for one thing. The thing which we all were seemingly glad to see the back of when a technology allowed us to bypass it. Yes, it’s the mapping. Automapping made maze-based games as obsolete as video made the radio-star. At the time, we shunned those who claimed to be losing anything as the sort of luddites who - to steal a line - responded to the appearance of writing as “But You’ll lose your memory”. But, in a small way, they were right. Since then, the RPG has been primarily defined by aspects like character-customisation and advancement. Fiddling with equipment is in the Bard’s Tale, but nowhere near as sophisticatedly implicated as – say – Neverwinter Nights or any other modern RPG.

But the vast majority of the Bard’s Tale is actually based around the simple process of mapping a closed environment. And, even after all these years, it’s fundamentally satisfying to make a map. With the square-based dungeons, there’s something soothing about the repetitive process of a move – pause – scribble – another move. Step by step, your knowledge of the world becomes more complete, and you’re inching closer to defeating Mangar. Your growing collection of maps are a physical representation of your progress. You’ve made something.

I knew I’d be glad I’d returned to Skara Brae. I’m surprised that it’s for a reason other than nostalgia. Less the Bard’s Tale, more the Cartographer’s Journey, there’s still more of a flash of adventure worth appreciating here.