Wot I Think: Dishonored

Rune For Improvement?

Expectations are high. A stealth game that utilises the brains of Deus Ex veteran Harvey Smith and Viktor Antonov, architect of the imaginary, would always be an intriguing proposition and Dishonored's industrial plague-ridden city is a curiosity that would stand out in any crowd, but in the particular crowd it finds itself in - early twenty first century first-person games - this is a game that stands out like a whale in a sardine tin. I've been sneaking my way through this brave new world, and now I feel obliged to tell you wot I think.

Dunwall, the city, is the star of Dishonored. Its inhabitants are cartoonish, mostly drawn in broad strokes and often at their best when they're absent, their stories told through recordings, diaries and notes. There are tableaux to discover - usually while exploring a derelict path, a building or alley without obvious purpose - frozen histories, dramas and tragedies that hauntingly tally up the human cost of the horrific plague and the ruling class’s barbaric prevention measures. That's when the people matter.

This is a revenger’s tale, with all of the high stakes, catharsis, double crosses and villainy that the form can play host to. But despite all of that - despite the cast of loyalists, rebels, victims, nobles and traitors – Dishonored is the tale of a city. And what a city it is. I haven’t wanted to study and explore a place as much as this since Thief introduced its marvellous warren of secrets, and it’s not only in its superb creation of an urban space both fantastical and relatable that Arkane’s game brings Looking Glass’s work to mind. Dishonored is almost certainly the finest stealth game I’ve played since the dawn of The Metal Age.

Part of me wants to just write a song here, a mad sea shanty, drunk on the delirium of this beautiful nightmare of a world. It’s London with a steampunk piercing and Pathologic’s blood-encrusted nail varnish. It’s watching a slaughtership bloodying up the river, slow and dominant, a dying whale spitted above the deck. At the end of all the many words below, there will be more words with numbers in front of them. A list. A list of the things that are in some ways more important to me than all of the thinking and pondering.

In a week or two, I’ll actually write something made of pure joy rather than trying to make sense of the game’s workings and describing why it’s not only a hugely entertaining and thoughtful game, but also why it’s remarkably important that it exists right now. We’ve been looking forward to Dishonored for most of the year and it has a great degree of expectation to live up to, but I hadn’t played it at all until I received review code last week. I’m glad I didn’t experience any sections out of context because this isn’t a compilation of areas and challenges, it’s a Rubik’s cube, interlocking components switching and accruing meaning as the player manipulates them.

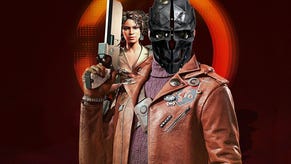

Here’s where the WIT takes an exuberant leap straight into the abstractions of this architectural wonder. Corvo, the masked assassin, is a Swiss Army knife. I anxiously flick the mousewheel back and forth and his left hand twitches in and out of view, my fingers prising at the various tools at my disposal, wondering which to ease from its casing. There is never a correct choice, or, more accurate, every choice is correct.

A non-lethal playthrough is possible and each mission can also be ghosted, with not a single living thing except the toothy rats ever aware of Corvo’s presence, but I reckon it’d also be possible to never use the left hand at all. Ignore all of the mystical powers and weaponry, and play the entire game using nothing more than the assassin’s blade, which is all but attached to the right hand, folding away and snapping to its full length in less than a second, ready to slay or to parry.

Most people, I expect, will be drawn to the idea of playing as precisely as possible, favouring the scalpel to the claymore. I certainly did, priding myself on sparing the lives of guards who might be good men in the wrong place at the wrong time. There are even non-lethal methods by which the actual assassination targets can be removed, although I didn’t discover them all and didn’t actually achieve any. I was also slightly more willing to murderise Overseers after hearing about and seeing them persecute innocents first-hand. They are the city’s resident religious authority, whose tenets of construction and craft are another echo of Thief. They are distinct enough from the Mechanists of The Metal Age but their theology and methods are similar, even down to their use of machinery to counter the ancient osseous magics used by Corvo.

The supernatural powers concerned me before I tried them out for myself. Wouldn’t ‘Blink’, an form of short distance teleportation, cause areas to be designed around its use, and indeed to counter its use? That there are so many ways to traverse each area and yet there are very few places that feel designed around a particular set of skills is the greatest compliment that I can pay to Dishonored’s architecture. There’s no equivalent of a cover-based shooter’s regular placement of chest high walls, the commas in a level’s gramma.

Human Revolution took place in a future where improbably vents were very much in fashion, while Dishonored approaches the problem of presenting alternate routes in a much more satisfactory way. In fact, it doesn’t present routes; at its strongest (which is most of what is at least twenty hours if savoured rather than scoffed), it presents places and leaves the player to make routes rather than finding them.

Put simply, if there is a building it will most likely have a roof, because that is one of the things that buildings have, and if there is a roof then it’s probably possible to be ON that roof. Perhaps you can blink there from a nearby window, perhaps you can find a way to climb up, perhaps you can jump across. Or maybe there’s a tiny gap that leads is the only entrance to the building and you can possess a rat, squeeze inside, and then revert to your human form once inside and just walk up the damn stairs.

If, like me, you think the powers might somehow make the stealth less tense and comprehensible, abandon those doubts right now. Like those extra doohickeys on the Swiss Army knife, the powers offer more options, different approaches to the problem of remaining unseen, or being swift and deadly. The introduction of the supernatural element takes place just before the first proper mission, following a somewhat rushed and relatively unconvincing introduction and tutorial section. Blink is unlocked straight away but other powers must be purchased using runes, which can be located in each area using a grisly item. It’d be possible to unlock powers that suit a violent approach, providing extra health, melee combos and the like, but I opted for stealth.

The combination of blinking and an extended jump makes moving through the levels feel surprisingly close to Mirror’s Edge rather than an FPS. Dishonored’s stealth is based around speed as much as silence and shadows. There’s a fluidity to movement that is perfectly sold by the positioning and reaction of the viewpoint when mantling, falling or leaping between rooftops. Control is extremely tight and precise, and after visiting a location a few times, I found myself capable of timing a journey through a district so neatly that the movements almost felt scripted. Jump, blink through a windowframe, sprint through a room, slide down some stairs, swivel, turn, dive through a window, land in a river to break the fall. All the while there might be bullets tearing through the air as pursuers’ failure to keep up with the chase makes Corvo seem like an impossible creature, a being of air rather than flesh.

Killing is smooth as well, whether from behind, silent and quick, or locking swords with the city watch. Blocking, parrying and striking are handled using two buttons, simple but effective, and every blow has a strong sense of impact. For ranged combat or takedowns, there’s a pistol and a crossbow. I’m a crossbow man myself and it’s a bit of a sniper’s weapon, with sleep darts being my weapon of choice. The pistol is more like a close combat weapon, actually, performing like a shotgun, a hand cannon, extremely noisy and extremely violent. For me it was a desperate unwanted measure of last resort; for others it may be the dispensary of justice.

There are no bosses and targets die just as fast as anyone else when they’ve got a sword through their face, no matter how important a person they might be. The quality does dip at times though and, as is so often the case, the denouement isn’t as effective as the rest of the journey. Pacing suffers a little as the end approaches, with a detour away from the streets that features a great deal of weepers, the diseased zombie equivalents of Dunwall, and the finale is the least consistently impressive area of the game.

That the tour is ending at all feels mournful and I immediately, greedily wanted more. At first I almost stupidly determined that Arkane hadn’t provided enough but that’s unfair. Dishonored is so dense, with both possibility and meaning, that I’ve already played most of it twice. Same places, different experiences, and that’s not just because I changed my approach. The city reacts to the amount of corpses Corvo leaves in its tenements and slums, with the plague and the guards both strengthening in response to the chaos his actions cause.

Kill more people and more rat swarms and weepers will creep into each district as the infrastructure collapses. At the same time, the false regent, afraid and angry, will deploy more troops and more technology in a bid to win back the streets. The tallboys, so iconic in the promotional material, aren’t as significant as I expected, but they stalk later levels in squads if the chaos level is high and can be punishing.

Oddly daft moments stand out all the more given the otherwise cohesion of world and action. One mission takes place during a masquerade and Corvo enters undetected, able to mingle with the guests rather than skulking on a nearby rooftop. It’s made clear that his mask is a disguise at this party, because everyone else is wearing a mask as well, but it’s quite a distinct mask and there are ‘Wanted’ posters all over the city with a picture of it on. Weird. Also unimportant when all’s said, but jarring nonetheless. (EDIT: Alec tells me the party guests repeatedly mentioned how clever/funny wearing the mask from the 'Wanted' posters was. I only heard a couple of snide comments and still think the guards should be more alert, but I'm less quibbly now) There’s a character with an ‘unassailable’ safe room as well but there’s a switch just next door that deactivates all its defences. Small niggles but the sort that make me think, oh, come on, you’re better than that. And the good thing is, Dishonored really is better than that, so all’s forgiven very swiftly.

That’s why Dishonored is important right now. It feels like a game from another timeline, one where Thief and System Shock set the bar for what first-person games could be, leading to designs that were built around intelligent use of space and world-building. I still wish Dishonored were longer but I also recognise that it takes a great deal of skill, hard work and time to create something of this quality; to ask for more in terms of content would be to ask for less in so many other ways. What we really should be asking is for other developers to learn the lessons that Arkane can teach them. Of course, it’s not as simple as that, because for all that there are flaws – there are always flaws – Dishonored is a work of rare imagination and skill, the sort of thing that can't simply be copied and repeated. I hope I'm wrong, but we may not see its like again for a good while.

After the two thousand words or so I’ve already spilled all over the screen, here’s a few personal thoughts:

1) Playing felt like watching the Marathon at this year’s Olympics, because it showed me a city I know in an unfamiliar way. Watching the runners on TV, I’d see a street or a building that I recognised and be slightly taken aback. Walking around Dunwall is similar. Every now and then there’s a place that looks so much like a part of London that I’ve actually been in that the whole experience becomes quite uncanny. It’s like somebody’s dream of a London that they’ve only seen paintings of in waking life.

2) There’s a pub, central to the entire game, that I feel like I’ve had a drink in. Several drinks actually. It’s a proper English pub and a far more believable boozer than some bars that I frequent in real life.

3) Runes aren’t just powerups. They are placed in a way that makes them a proper part of the scenery, often with a background as to how they wound up where they are. It’s like when a game doesn’t just have guns and ammo scattered randomly through its levels, but places them in lockers and armouries. Dishonored positions everything with purpose.

4) Dogs will eat your face.

5) Rats will eat all of your flesh, but not if you distract them with a corpse to chew on. I once shot a guard with a sleeping dart and was then horrified to see a swarm of rats converge on his fallen form and strip it down to the bones.

6) There are grenades. I am so sneaky I’ve never even tried to use one. As much as a screenshot might make some people believe this is an FPS, it is a game in which explosives can happily be snubbed rather than fetishised and desired. Explosions are not the main character/feature.

7) Food has names and by reading books it’s possible to find out where the various fruits and meats come from. There’s a whole world beyond Dunwall, with histories, cultures and connections. There are also maps that are little more than names of faraway places. There’s romance in those details.

8) There are sidequests, many of which seem to alter aspects of the world and characters later in the game.

9) The voice acting is American, which seems a peculiar choice. There’s one chap who sounds like Heath Ledger’s Joker.

10) I want to see the rest of this world. I want to travel on a whaling ship to distant lands, to see the horrors and the wonders, and to see if the plague has spread farther afield. I also kind of want Dishonored to stand alone and for all the references to be nothing more than the well-practiced art of allusion.

11) Early in the game, an item is received that provides thoughts and feelings about areas and people. More depth and poetry, mostly just for its own sake. It even reflects on itself, scared and sorrowful.

12) Dishonored wants you to play it however you want to play it, unless you want to play it like Monopoly or something, in which case you will be disappointed. I'd suggest playing on 'hard' because tension and danger are the things that make my life worth living. I would definitely recommend turning off objective markers. There are loads of options for feedback and markers and the objective one will always point you to the next point, whether it be the transition between two areas or an assassination target. It also marks secondary objectives, which are optional. Turn it off because you want to explore and learn to read the world, don't you?

Dishonored is out between the 9th and the 12th of this month, depending on how long it takes for a whaling ship to deliver it to your part of the world.