So Very Many Happy Returns: Half-Life Is 15 Today

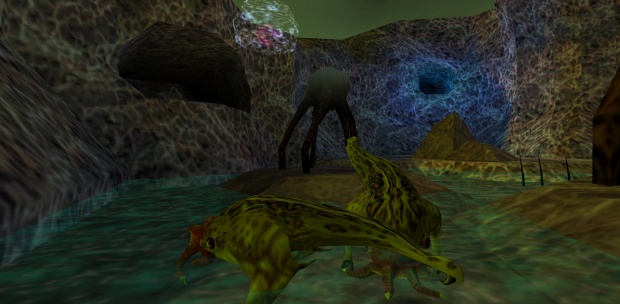

Eat this, you outer-space octopus

Half-Life celebrates its 15th birthday today. Valve's genre-exploding, literal game-changer first appeared on the 19th November 1998, taking the well-loved first-person shooter and crafting something extraordinary. It was considered a turning point. A new bar for games to beat. And one that was safely broken by, er, Half-Life 2 six years later. Below are some of RPS's favourite memories of the old, old game.

Graham: I haven't been writing here long enough to do one of these yet, but: Half-Life Made Me. And I didn't even like it that much at first. It felt sluggish compared to Quake and I got stuck at its three-headed tentacle boss. I was only able and inspired to progress months later when a friend began phoning me to talk about it every day.

Which started the slippery slope towards everything my life is today. I remember hosting deathmatch games on 56k modems. I remember finding an illegally sold disc of custom Half-Life levels in a tourist shop somewhere in England. I remember hearing that Worldcraft, the game's level editor, came on the game's install disc. I remember joining forums and IRC rooms and making friends and slowly learning how to use it. I remember the confidence that gave me.

I remember Counter-Strike. I remember Day of Defeat, Frontline Force, They Hunger, USS Darkstar, Age of Chivalry, Pirates, Vikings & Knights, and Half-Life Rally. Action Half-Life! Wanted. Sven Co-Op. Snark Wars? Scientist Hunt.

I remember beginning to write for a Half-Life 1 map review site and producing my first published articles. I remember befriending someone at Valve and writing reviews for the official Valve editing site. I remember starting my own fan site and interviewing modders and mappers. I remember the time I got 250,000 visitors in a single evening because I scanned the 'Next Month' page from Edge magazine, which had a crowbar on it casting a shadow in the shape of a 2. (Sorry, Edge.)

I remember completing the game more than I've completed any other game, and spending every waking moment writing or making something devoted to it. In retrospect, there's maybe very little I don't remember. Fifteen years later, there's a lambda symbol still seared into my brain.

John: When I think about Half-Life the very first things that come to mind are crowbar, intro sequence, that first broken elevator, Xen, the noise of a face-hugger... Memories pour in, dozens of them, faster than I can keep up with. There are few games that my brain stores in such detail. But of everything in the game, I think the most exciting, most thrilling moment, was that time when the enemy soldiers started fighting the enemy aliens.

I'm sure there are examples of this happening in a dozen earlier games, perhaps even some I played, but this was the moment for me when a game became something bigger. It was taking place despite me. Not in the horrible way now too familiar in modern shooters, where the realisation of your own irrelevance renders the whole experience moot. But in a way where if I didn't shoot them first, they might start shooting each other. I could watch the game taking place in front of me, without my being directly involved in it. Then leap in when it suited.

Half-Life had already developed a sense of place like no game before it. Despite the outlandish sci-fi tale, it created a real-world environment like nothing else. In fact, I remember the first time I saw screenshots of it in a PC Gamer preview, my brain almost couldn't comprehend that someone was going to set an FPS in a recognisable location - offices like offices I'd been in. (It wasn't until I first visited Seattle years later, and rode the airport's monorail, that I was aware how true to life that bit was as well.) So with an Earthly foundation, then having this moment of autonomous warfare amongst the AI created something utterly incredible. Or indeed credible. That's stuck with me ever since.

Adam: Xen doesn’t exist in my memories of Half Life. That’s not entirely true, obviously, or I’d become angry and confused every time somebody mentioned ‘that shitty alien dimension bit’. Xen is in my brainbox somewhere but I’ve managed to shove it into the closet where I keep the skeletons and R Kelly.

That’s not quite true either though. I didn’t shove Xen into the closet. It clambered in of its own accord. An ill-judged moment, particularly an ending, can eradicate all the goodwill that any piece of entertainment has generated, but that's not the case with Xen. It is tedious, but the short interdimensional trip into the land of floating platforms doesn’t mar the highlight reel that runs through my head when I remember my first playthrough of Valve's masterpiece. I still think it's their strongest game but back in '98 it wasn't even the best game I bought that week. Truly a golden age.

The scenes haven’t faded with the passage of time and that’s at least partly because they’re all marked by sound as much as vision, and audio doesn’t date in the same way that the Quake engine has, even in such a heavily modified state. Half Life’s immersive world owes a great deal to the audio design that made vents into claustrophobic coffins and was at the heart of the game’s greatest set piece, in the blast pit. The tapping and clanging of the tentacles as they sought prey was horrifying enough, but the sonar screams of the creature itself came from somewhere deep and (mercifully) unseen. We saw its body but we never saw its home.

Then there was the chatter and barking of the soldiers, a brilliantly stitched veil that brought them out of AI’s own uncanny valley. I believed that they were flanking me, thinking one step ahead. It’s a beautiful illusion and Half Life was full of them. I don’t remember it as the story of a scientist, I remember it as a model of convincing environments and behaviours, and it’s still one of the best I’ve ever played.

Alec: It took me two years to complete Half-Life. I'd fallen out of PC gaming at the time, as the costs and social whirl of university assumed temporary priority over the unknown worlds I'd spent my teenage years in, but this was the game which brought me back, even if it took its time about it.

'Play this', said a schoolfriend who'd gone to the same university as me, pressing a Sharpie-scribbled CD-R into my hand with some urgency. (Sorry, Gabe). I knew nothing of this 'Half-Life', and indeed asked little about its nature or content at the time - I was entirely fixated upon the fact that this was a game which required a 3D card. I barely even knew what 3D meant, having not followed gaming tech for a little while - indeed I fear I interpreted it in the Avatar sense, and was faintly disappointed to find it basically meant 'like Quake'. (Though I can remember moving the camera around on the game's opening monorail ride, convincing myself that the train seats were jutting out of my screen, in the manner of a young drug virgin being given ground-up paracetamol by amused, more streetwise peers and told it was E or whizz or Cake or something. 'Yeah, yeah, I can feel something now!')

This chance act of nonchalant piracy coincided with a Christmas or a birthday - I can't remember which - so to spare my parents the embarrassment of my requesting 'booze or cash' yet again when they inquired as to what gift I desired, I elected to ask for a Voodoo 2 Graphics Accelerator. I did no research about it, so had no idea if my PC would take it or what I'd need to install it, but it all sounded terribly exciting. When it arrived, it appeared my PC did indeed have the requisite slot, so I popped it in, ran the daisy-chain cable to my monitor, installed some complicated driver software off a floppy disc and then, finally, installed Half-Life. It ran! A modern videogame, with guns and everything, running on my old PC! This Voodoo thing was amazing!

Except it wasn't. Unknowingly, I played the first half of that game in software graphics mode because I hadn't pushed the Voodoo fully into the PCI slot. The game ran fine, but with edges more jagged than the glass which decapitated David Warner in The Omen, and textures like a field in Glastonbury after three solid days of rain. I cared not, for this sci-fi Indiana Jones adventure was so magnificent, so atmospheric, so challenging and surprising, so very there compared to the abstract Dooms and Quakes I'd played during my last love affair with PC gaming.

Unfortunately, software mode rendered water as an opaque grey-blue sheet, so after one too many aggravating attempts to survive and fight a space-shark I couldn't even see, I gave up and told people that '3D gaming was bollocks' and went back to getting drunk and pining after girls I was too shy and badly-dressed to ask out.

Two years later, another friend was taking a look at my PC for some tech support problem I can't recall, spotted the ill-fitted Voodoo, knowingly applied a thumb to its edge and was rewarded with a confident 'click.' After his mockery had died down, I loaded up Half-Life again. I blinked in disbelief at this sharp-edged, colorfully-textured, transparent-watered vision of a future that everyone else had experienced 24 months ago. I saw the shark, shot it with a crossbow, went for a long swim in a gloriously see-through pool. I played the rest in one astounded, hungry, grubby, weekend-long sitting, and PC gaming and I have never been apart since.

Nathan: The G-Man won't stop following me.

After a Warcraft, Diablo, and StarCraft dominated childhood, I shamefully lapsed into console gaming's fickle embrace throughout my early adolescent years. But then one day in middle school computer class, I overheard the Cool Nerds (who I never worked up the guts to actually hang out with, sadly) chatting excitedly about early screens and information about something called Half-Life 2. “Half-Life 2?” I pondered to myself. “I wonder if they'll eventually bundle the first and second together and just call it Life.”

Half-Life 2, of course, didn't come out for years. In the meantime, however, I dug into the original Half-Life and dug in deep. As a bumbling, stumbling, swamp-skinned embodiment of preteen awkwardness, I didn't exactly have the most rollicking social calendar. My dumb offhand thought ended up being oddly prophetic: Half-Life became life. Mine, specifically. I played it front-to-back in that obsessive way only kids really can. The “just another day on the job” opening. My first far-more-difficult-than-it-should-have-been headcrab encounter. Tentacles! Scientists. Xen. The ending and its perfect full-circle callback to the beginning. Man, what a ride. Every. Single. Time.

I always loved games for their stories – pretty much from the moment I first started playing them. Whether it was StarCraft's space opera of grimdark love and loss or Goldeneye's sweaty, desperate attempt at faithfulness to its source material, games shoveled fuel into my imagination's engines, impossible worlds given shape and form. Half-Life was a turning point. Compared to everything else I'd played previously, there was so much more to tear apart, dissect, and devour. It also welcomed me back into PC gaming's hallowed halls, and I never left again after that.

G-Man followed me elsewhere, too. Counter-Strike allowed me to briefly rekindle a relationship with a childhood best friend and bond with an older cousin I didn't have much else in common with. Half-Life and Half-Life 2, meanwhile, indirectly spawned half of the in-jokes my college friends and I incessantly repeated until entire rooms attempted to saw off their own ears when we were around. “Gordon Freeman? Gordon Freeman!” we'd repeat in high-pitched bellows, imitating the magnificent Half-Life in 60 seconds video. And don't even get me started on Half-Life: Full Life Consequences. Let's just say I can still quote the entire thing. With voices.

I am not proud of that fact. Well, OK, maybe a little.

But for every goofy video, there was also a wonderfully clever comic like Chris Livingston's Concerned or a magnificent mod like the original Natural Selection. I guess what I'm saying is Half-Life – the whole series, really, though especially the first – inspired plenty of other people's imaginations too. Many of them went on to do big things of their own after that first spark, to become excellent creators in their own right.

In that sense, G-Man – who by now you should understand is a (still really creepy) metaphor wooooooo – continues to follow me, a clammy invisible hand tugging at the strings of my reality. I wouldn't have it any other way.