Toast To The Monsters: 20 Years Of Doom

Now that was something

20 years since the course of videogaming was set forever. 20 years since id created what may very well still be the most notorious game in history. 20 years since deathmatch became a thing. 20 years of guns, 20 years of keycards, 20 years of happy hell. 20 years of Doom, not the first first-person shooter but surely the foremost breeding stock of the genre. Happy birthday, old stick.

If only you could talk to the monsters on their birthday - now that would be something. Instead, Team RPS will have to reminisce about the big, brash first-person shooter that changed everything.

John Walker:

I wonder how many times I can tell the story of when Fred Sharrock came over to my house with his PC, and we set them up in my dad's study, connected them together via some magical lead between printer ports, and APPEARED ON EACH OTHER'S SCREENS.

Let me try to break this down for you. We weren't both appearing on the same screen. And this wasn't two screens plugged into one computer. We were on different computers, but inside the same game. I'm not sure if you'll be able to get your head around that. We couldn't.

I also remembering hacking my sixth-form form room PCs so we could install it on a whole bunch of them, and then achieve this same voodoo magic at school too, until we eventually got caught.

It's odd that after my really quite considerable excitement at this phenomenon, I've gone on to avoid multiplayer and co-op as much as is humanly possible. But Doom is special, right? Of course Doom is special.

On that recent Charliebrookerthon I remember Rab Florence comparing how odd it must be to the younglings of today to know we oldies were scared by Doom, with our own incredulity at those who ran screaming from cinemas at the sight of a train heading toward them. With the greatest of respect to Rab, I'm not sure that comparison stands, unless a train actually did burst forth through the screen and flatten the smug few who remained. Because Doom IS scary, and I challenge anyone to not find it so playing it today.

Once the fifteen seconds of caring about the relatively primitive graphics are over (perhaps twenty seconds if you insist on a few more confused laps of a 2D/3D crate and their reality-bending ways), then it's every bit as much the lightning-fast, screeching, roaring carnival of shocks and horrors it ever was.

It's definitely the game I've finished the most often, each time equally delighted by the awfulness of that bunny's head, and tricking my sister into looking at it. It's the game whose sound effects are most imprinted in my memory, such that every time anyone else still uses the same CD of SFX id clearly got them from all I can think of is Doom. It's a technical masterpiece, the progenitor of so very many of the best games, and at 20 years on, a reason to feel incredibly, incredibly old.

Alec Meer:

I didn't have quite the out-of-nowhere-whaaaaaaaaaaat response some did to Doom, as I'd come up through Catacomb 3-D and Wolfenstein 3D by that point and had, for my young years, a reasonably defined sense of where things where going and what I most enjoyed from games, which at that time was shooting and secrets and mazes. I remember, oddly, thinking 'yes, this is just right, this is just what I expected' when playing Doom: it just made sense that my PC could conjure these scenes, and a descent into this handsome hell was not simply welcome, not simply necessary, but inevitable.

After fanfare and floppy disk were given their due (and that day at school on which I was given said disk could not end soon enough), playing it was like instantly slipping into a pair of well-worn, comfortable slippers, but slippers I'd never seen or perhaps even imagined before. I played a lot of PC games in the early-to-mid 1990s, but I am quite sure then as now that this was one of the most instrumental in ensuring I would become a game-player for life. I remember, as strongly as I do the game itself, the buzz around school, the sense of some epochal arrival, bigger than any petty concern of grades or gangs or friendships or rivalries or football or who wore what: "have you played it? Have you got it? Can you give me a copy?" A drumbeat echoing around the halls, the lockers, the backpacks and briefcases, the brains of us all. Doom. Doom. Doom. Doom. Doom.

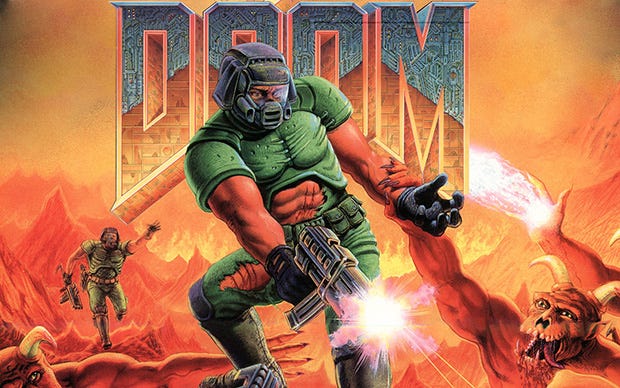

I marvel at how iconic Doom's elements are still, its Imps and shotguns and chainsaws, its Cacodemons and Cyberdemons and its space marine in green armour. Then I wonder if, like Star Wars, this is simply a consequence of being the loudest voice amongst those first on the scene, if another game with a similar idea at a similar time would have wormed its way into the popular consciousness in quite the same way. But I like to think there was some grand, accidental alchemy in Doom that made its monsters seem quite so singular, its arsenal so instantly archetypal and its colours and music and sound work in such unison. This was Meant To Be, a fixed point in time that had to happen. I find, unlike so many games of its ilk since, Doom to be relentlessly replayable, a fluid balance of speed and violence, reflex and planning whose visual design remains striking in the face of its increasing age.

The first level is music to me, a familiar rhythm of bullets and doors and demons that something deeper than my consciousness knows and responds to, finger-dancing to each beat. The right game at an impressionable age, aided by this glut of celebratory, lascivious nastiness being a feral cat among that gaming age's relatively innocent pigeons: I know all that timing that has a great deal to do with Doom's ongoing appeal to me.

No matter, though, how many thought experiments I try I just can't imagine Halo or Call of Duty or Borderlands or Bioshock being My Doom, had I arrived later to this world. Is it just nostalgia? Perhaps, but I'd much rather keep on believing that there's something more, something landmark and something undying about Doom, purity of design in expert concert with puerility of tone. I'm not alone; the knowledge that there is a still-growing world of WADs and remakes and ports and more out there for me to one day explore, makes me very happy.

For all that, I would so love to visit the world in which Doom never happened. Perhaps it's a better one. Perhaps it's dumber still.

Adam: Doom is the first and only game that sold me on a system, and that system was my first PC. I played id’s paragon of demon-shooting for the first time when I was fourteen years old. I was visiting my friend Alex, after school, and he’d shown me Wolfenstein 3D a few weeks before. It was revelatory.

The only first-person games I’d played at that point used a grid system – Dungeon Master, Eye of the Beholder, Captive – and the way that Blazkowicz slid through the world was the most immersive and technically incredible thing I’d ever seen. The world’s only surviving reciprocating steam engine flywheel alternator, which my grandfather had excitedly introduced me to at the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry, had nothing on Wolfenstein.

“They’ve made another one.” Alex said, proud to be the keeper of secrets. “The people who made this. It’s the most violent game ever made.”

We sat in silence for a moment to let those profound words permeate the room.

“Do you want to see it?” Of course I wanted to see it. What kind of stupid stunt is my exaggeratedly dickish memory of Alex trying to pull here? “I’m getting a copy next week.” Argh! Fuck. That was no good to me. I needed to see it right there and then. “There’s a screenshot in this magazine.”

And, bless me, there was. Lurid and large on a page glossier than a thousand internets, it depicted a chainsaw being thrust into a cacodemon’s eyeball. I pretended that I thought it was the most amazing thing I’d ever seen but, in truth, I was a bit disappointed. It all looked a bit messy and too colourful. A bright red demon with glowing blue blood? I think teenage Adam, idiot that he was, wanted more browns and greys. He’d be happy as a champion today and I distinctly remember how much he loved Quake.

Undeterred by the lurid screenshot, I realised that I had to return to Alex’s house when the game arrived. This is the same chap who, later in life, would convince me to swap my best Spellfire card for a one night ‘lend’ of his copy of Duke Nukem 3D. He was the kind of friend who knows the value of his superior ability to wangle goods and services out of parents wealthier than the neighbourhood average.

With Doom, he didn’t ask for any favours or trades. Instead, he allowed me to visit, loaded the game and then sat playing it for three hours without letting me have a single go. “It’s mine,” he explained, simply. “But you can watch.” I think he fed off my steadily increasing desire.

That night, when I got home, I began my campaign. I needed a PC because I needed Doom. I loved my Amiga but would it ever be able to emulate the smooth, bobbing movement of a space marine in an alien-infested base on Phobos? It didn’t seem likely. What about the gloriously sloppy animation of an imp covered in exploding toxic waste? Fat chance.

I told my parents I needed a PC because everyone at school had one and that it would help with homework, and that I really really wanted to learn how to be the best computer software man, and that the Amiga was RUBBISH (oh god I’m so so sorry it was a lie).

Somehow it worked. I never became a computer software man and I did most of homework with a pen and paper, but I did get hold of a copy of Doom. Just the shareware version for the longest time. I’ve probably spent more time in the opening level - which I still think of as nothing more than E1M1 – than in any other piece of imaginary real estate. The music, the secrets, the placement of the enemies are as clear in my mind as they were seventeen years ago.

Doom was my first LAN game, my first FPS game and my first PC game. Like a kid who graduates from the illicit thrill of video nasties to the wider world of cinema, I unintentionally treated Doom as a gateway game, moving swiftly through genres and the history that I’d missed. That’s not to say I’ve moved on though – every house needs a gateway and Doom’s a hell of a one to go back to every once in a while.