Premature Evaluation: The Magic Circle

Hole Kaboodle

Each week Marsh Davies plays unfinished and broken games on Early Access and usually tries to come up with an introductory sentence which says exactly this while using imagery appropriate to the idiom of the given week’s game. But the idiom of this week’s game is being an unfinished and broken game! So, job done. It’s The Magic Circle [Steam page], a game set within a game, in which the player edits the properties of the world around him while exploring the strata of the game’s many abandoned developmental stages, unravelling the story of its creators in the process.

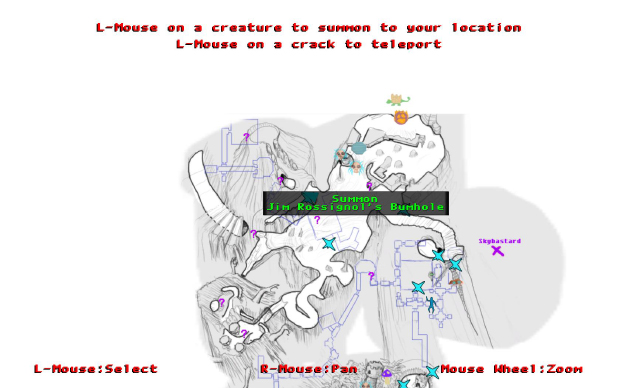

I have tamed Jim Rossignol’s bumhole. I’ve also made Jim Rossignol’s bumhole fireproof, which is just as well, since Jim Rossignol’s bumhole spews gouts of flame when angered. Jim Rossignol’s bumhole has a lightning rod jammed in it, too, which deactivates forcefields. With my latest effort, Jim Rossignol’s bumhole has sprouted a little propeller, allowing Jim Rossignol’s bumhole to fly about. John Walker’s angry red Weeto has many of the same properties, and it should surprise no one that Alec Meer’s huge husky third leg is shaped like a ginormous mushroom.

Jim Rossignol’s bumhole is - of course! - an ugly AI dog-monster, whose name is just one of a large number of editable fields, which, when tweaked, imbue him with various properties. Diving into an edit mode, you can flip flags for the AI’s behaviour, and if you’ve “learnt” the verbs for it, Jim Rossignol’s bumhole can float or fly. You can choose with whom he’s allied, whom he attacks, and by what means. The Magic Circle is a game about game development itself, in which you play an interloper, an errant playtester committing sabotage in the code of an unreleased vaporware epic. The principle system by which this is expressed is through the editing of AI attributes, stealing properties from defeated foes, and using them to empower your allies, until you have a small army of flying, flame-barfing beasts at your disposal. Maybe then, you can take on the Gods of this world - the game’s bickering, despondent developers themselves, locked in a crunch-cycle that has lasted ten years.

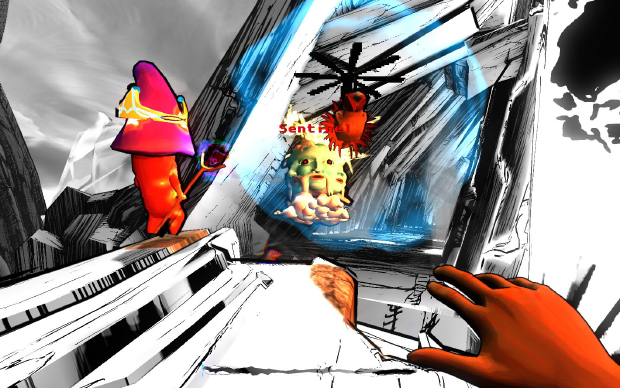

It’s an idea I like very much - having the player explore in first person the ossified layers of abandoned development as the troubled project jinks and u-turns through various thematic eras. The Gods themselves are present here, at least at scripted intervals, sweeping through the landscape as giant floating eyes, editing and deleting, tussling for creative control. Their personal battles also play out through developer commentaries and other audio diaries - though the reasons why office chatter and other personal observations make their way into the game are a bit of a narrative stretch. Using this canvas, The Magic Circle’s developers (the real-life ones, not the in-game ones) play with the literacy of the players themselves, unpicking mechanical cliches, exposing the human drama and developmental struggles which lie behind them. If you’ve ever spluttered with irritation at an imbalanced enemy, broken hit-detection or unclear signposting, The Magic Circle has pithy explanations for how such obvious errors could come to be.

One of the pitfalls of this however, is that often you find yourself playing an unfinished, broken game set in a stridently ugly fantasy world, whose clumsy polys are rendered as a crude, pseudo-cel-shaded sketch. This is, unlike the vast majority of Early Access releases, largely by design, but I’m not entirely sure that helps much. Those low-level interactions that players subliminally enjoy - the precision of collision, the pace of movement and the arc of a jump - feel all out of whack here, and the in-fiction explanation doesn’t do much to make glitching off some peculiarly slippery block during a ghastly, punishing platforming challenge feel any less abrasive.

I also have reservations about the way the game’s central AI-behaviour-changing system operates. The devs suggest that some of this may be tweaked based on player feedback during its six week stay in Early Access, but, even with this caveat acknowledged, I have to confess that I just don’t find it all that systemically interesting. The variance and combination of abilities doesn’t really create surprising synergies or complex interactions. When the narrative motivations of the world are stripped away, the mechanistic impulses currently feel as bare and linear as a point-and-click’s trammelled solutions: go here and kill this enemy to attain its ability so you can go there and kill that enemy.

What freedoms you do have to play creatively with the system are constricted in odd ways that have yet to enhance the strategy of the game for me. The nouns and verbs which constitute your available choices for AI attributes are a limited resource; strip a “flying” flag from a creature and you can dole it back out to just one other. I don’t really see the reason why it shouldn’t just be permanently available once acquired - it just means you spend more time clicking on dead bodies to strip their nouns, and, having solved the “puzzle” of which creature will give you what necessary skill, there’s no real suspense or excitement in having too few opportunities to apply it.

Similarly, behavioural edits happen per creature, rather than globally to their entire species - and I’ve yet to find an instance in which the efficiency of the latter would not be preferable. Creatures must be summoned to be physically in front of you in order to edit them, which, when you have a small army of minions, is not the ideal interface to pick and choose among them. There’s one occasion when you find an enemy which does disseminate its characteristics to creatures within its hive, but it can’t be summoned, meaning that in order to edit its subsidiaries, as I found I needed to repeatedly, I had to traipse across a large chunk of the map from the nearest quick-travel location. Weirdly, there is no run button.

Combat itself is hugely unglamorous and hard to parse - the developer characters even comment on how crude it is. But this means it’s hard to see if your solution to a puzzle is working, whether the skills with which you have equipped your creatures are sufficient. In several battles, the enemy had such a large, invisible health pool, and no way to indicate that it was taking damage, that I had no idea if my creatures were doing anything to it at all. After quite a while of watching Jim Rossignol’s bumhole being skewered, and resurrecting him from our shared life-pool, I was poised to give up - then the suddenly enemy died. At that very moment, I was clicking to resurrect John Walker’s angry red Weeto, but the game retargeted my resurrection ability to the enemy, bringing it back to full life straight away, forcing me to fight the entire tedious thing again.

Maybe that’s just bad luck: I don’t hold it against the game. And, with regard to my larger dissatisfactions, I’m sure I’m doing something wrong. Maybe I’m not seeing some part of the system correctly, or I just haven’t made enough of an effort to min-max my creatures’ stats - but it’s at least partly because this stuff feels fussy and obscured. The interfaces for the game are, in keeping with its aesthetic, clumsy and unappealing.

More successful is the aesthetic switch between different eras of the game’s development: the monochromatic fantasy world gives way to a deprecated sci-fi-horror setting, reminiscent of System Shock, and it attentively recaptures that game’s palette and resolution. But the game never quite makes a case for why these settings - the cliches of which are affectionately lampooned - appealed to their developers or what the designs strived to do. It establishes the lead developer as a megalomaniacal auteur trying to recapture his fading glory, but never really explains his genius or gives reason why his earlier games touched people’s lives.

It’s perhaps not fair to hold it to a standard of another medium, but I can’t help but compare The Magic Circle to Austin Grossman’s novel, YOU, also set across the arduous development cycle of a long-awaited game, and often within the game, too. It exhaustively explains just how bold and ambitious the early, simulatory RPGs like Ultima were; what pioneers their developers were; how weird, intricate and exotic such layered, historied developments can become; what it means to be a player, creator or an inhabitant of such worlds.

The Magic Circle just doesn’t muster the same depth in its analysis, though it gestures towards many of the same themes and attempts introspection via a cute appropriation of game dev tools. I remained entertained: it has some tremendous, energetic vocal performances, and a cleverly orchestrated four-way struggle among its leading characters - the auteur unable to realise his vision, the burnt-out dev trying to get herself fired, the obsessive fan and an abandoned AI protagonist. It treads an awkward path between satirical caricature and more earnest attempts to humanise these characters. But, ultimately, given a world intentionally constructed from cliche, and only part-constructed at that, The Magic Circle felt to me a little glib, lacking, in fact, the very magic which animates this weird and wonderful medium.

The Magic Circle is available from Steam for £13.50 until May 20th and £15 thereafter until its full release. I played version 1357 on 13/05/2015, although, on reflection, that may be an in-fiction build number.