RPS Discusses: Which Is The Best Level In PC Gaming?

Or map, if you prefer

Level 28! No, the other kind of level. The type that you run around in, shooting people or jumping on their heads and that sort of thing. Adam, Alec, Alice and Graham gather to discuss their favourite levels and/or maps from across the vast length of PC gaming, including selections from Deus Ex, Call of Duty and Quake III. Someone even makes a case for Xen from Half-Life, and means it.

Alec: What is your favourite level in an electric videogame? Anyone saying anything about Mario will be flayed. Arbitrarily, Adam can go first.

Adam: I was going to do the obvious thing - the obvious thing for both me and RPS as a whole - and pick a level from one of the Thief games. One of the scary levels. Probably The Cradle.

Instead, I’ve decided to shout about the merits of a couple of missions from Call of Duty. Yes, Call of Duty. The first Call of Duty. I went back to replay it recently, with the idea of breaking down how the series has changed over time, and was absolutely won over by it almost immediately.

The specific level I picked out is Brécourt Manor, which contains everything that I love about Call of Duty and none of the crap. It’s fascinating because it comes immediately after the first big blunder in the game - a silly car chase that takes away all agency AND makes the war feel like a jape. It’s the first time that’s happened. If you haven’t played those first CoD games in a while the most surprising thing about them is how harrowing they can be. Loud, chaotic and full of grim meaningless death that doesn’t even have the dignity to happen in slow motion with an orchestral dubstep score behind it.

Brecourt Manor has you taking out several artillery pieces and there are desperate moments when you’re clearing out buildings, shooting people up close and personal. There’s no glory in it. It’s bloody horrible. And then you’re pinned down between two buildings, then creeping forward inch by inch, foot by foot, as people drop like flies and their names blink out of existence.

It’s a really bracing reminder that Call of Duty cared about portraying battle in a way that emphasised the chaos and deadliness of an area thick with bullets. It makes you feel like a person trying to survive an awful situation rather than a person trying to win a war. It’s genuinely superb - more of a standout than the Stalingrad and Normandy missions - and I’m not going to use it as a stick to beat modern Call of Duty (mostly because I don’t play modern Call of Duty so I’d be comparing it to a bogeyman) but it does highlight how brilliant military FPS games can be.

My favourite level is probably Lord Bafford’s Manor though. Or Doom E1M3, which I’ve been weirdly fond of since I first played it.

Alec: It’s remarkable how rarely anyone seems to look at or even reminisce about CoD at that kind of detail - I’ve read little on why the initial games did war so well, though I have parrotted the line that they did myself all too many times. WELL DONE ADAM. Does that level successfully mask the whole infinite respawning until you pass the trigger line thing, then? I tended to find that looking too closely at a CoD ruined the whole thing. Like in Half-Life 2’s Ravenholm where you can find the exact spot the zombies spawn from.

Adam: It hides it more effectively than some of the other missions, mostly by hiding line of sight of the enemy lines a lot of the time. I forgot to mention that it starts in trenches and manages to make sense of the respawning by having you ducked down and unable to keep track of enemies. It’s smart stuff - a weirdly unspectacular spectacle, which is probably a frightening accurate portrayal of some kinds of combat.

They key thing I took from it was a sense of relief when it was done. Which is the kind of line that I’m fairly certain I’ve read about some COD games in an entirely different context.

Graham: I think the levels I find most impressive are normally designed for singleplayer use; that Gone Home constructs a believable and functional suburban home that serves its story, or the way Minerva: Metastasis winds inward to make efficient use of Half-Life 2 memory limits, or the way interior design in Mirror's Edge is used to provide the player with unconscious hints as to which way to turn at the end of a corridor.

But the maps I love - that I have spent the most time on, and therefore have the fondest memories of - are always multiplayer. Even when they're not very good maps for not very good game modes, in the case of - and I'll talk about my favourite later, but - the Half-Life deathmatch map Crossfire. It was a set of grey builds re-purposed from the game's singleplayer as a playground for the game's better-for-singleplayer weapons, but it had a button on one end that caused an alarm to sound, blast doors to slowly descend, and an airstrike to kill everyone outside some 60 seconds later. I played it over and over and it produced dramatic, funny situations every single time - all thanks to that button.

Do others feel the distinction between the amount of love they have for multiplayer and singleplayer maps?

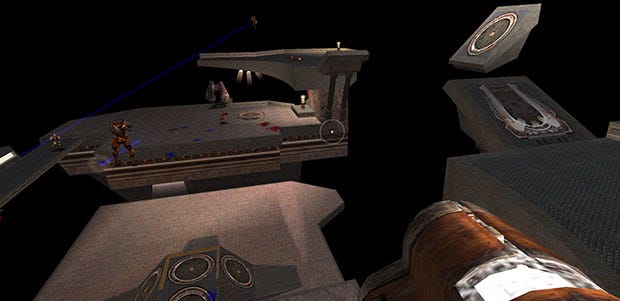

Alec: I wonder if the distinction is less between single and multi and more the difference between somewhere you visit and somewhere you live? Like, my most memorable singleplayer maps - like the first zone in STALKER, the Tentacle Beast in Half-Life 1 - are the ones that you had to spend a long, long time in before you could move anywhere else, even revisiting areas or seeing repeating scenes with tweaked contents. Most SP levels you just sprint through and right out of, seeing a section for a couple of minutes and that’s it. When you stay in one place, as you do in multiplayer, it starts to feel like your place, rather than someone else’s. But yeah, the harrowing, wall-less world of Q3DM17 feels like home because I’ve spent hundreds of hours in it, whereas any number of amazing maps from BioShock, say, are whispers in the wind.

Adam: I haven’t played Unreal Tournament for years but if you sat me down with a pen and paper, I could draw three or four maps. One of my mates at school made a Quake deathmatch map and I probably spent more time in that over the next couple of years than any other level in anything ever. There was lava and buttons that opened pits into the lava. PROBABLY.

(Brendon Chung's fan art for Q2DM1, The Edge)

(Brendon Chung's fan art for Q2DM1, The Edge)

Graham: I could draw - and have drawn - maps of my favourite level, too. Though level seems like doing it a disservice: it's Chernarus from DayZ. My leading question about multiplayer was a clever ruse so I could talk about a place that straddles both, because I think that's where much of its power comes from.

Chernarus was built for a simulation war game and so feels more like a real place than a 'designed' space. It's not peppered with low walls for handy cover, but awkward hedgerows, barren fields, farm buildings spaced with a natural rhythm rather than game design in mind. That makes it a wonderfully immersive place to be, but also the perfect setting for a zombie game, in which the real world is meant to have gone wrong and the normal has suddenly become horrific.

Alec: How much of that is, I guess, designed, as opposed to an accident of how much time you spent there, the unintended meaning this one house that had a backpack in or that hedge you almost got chomped behind takes on? I.e. is the layout of Chernarus actually great, or it was a happy accident that it was such a fine backdrop for monstrous events?

Graham: I think it is a beautiful place. I think it is a staggering technical achievement. I think it takes incredible skill to make a place that feels real without feeling boring. But I think its ungameyness, its simulationness, its realywealyness, is what gives it tremendous power when you drop zombies and backpacks and tell people to survive there. Which probably isn't an answer to your question.

Bohemia deserve credit, because who else is there to give it to, but there's a sense in that place that, if you were to design it with a zombie game in mind, you'd never make it look like that. You'd never have long, empty stretches of countryside if you were making a game in which people would be travelling by foot 99% of the time, for example.

Adam: I was playing DayZ last week and pretty much everything you’re saying there rings true. Seeing a zombie, or even another person, feels unnatural in the best possible way. It’s as if someone had been location scouting for a modern war film and received the wrong screenplay in the post. The sound design has a huge impact as well - times of day are recognisable by sound, even if you’re indoors or hunkered down not paying particular attention to the quality of light. It feels more like walking in a real place than any walking simulator I’ve ever played.

Alec: What about you, Alice? Why do you love Liberty Island and Dear Esther so much?

Alice: I am foolishly hungover, don't bully me.

Like Graham, multiplayer levels are dearest to my heart, but mine are more from mods - from specific builds of mods, and specific versions of levels. When everyone got So Very Professional in the Half-Life days, levels were never really finished, with each new beta tweaking - or massively reworking - something. Half a map might vanish overnight, taking your favourite areas with it. Or a change in weapon balance might make certain parts of the map pointless. The levels I'll call my favourites are terrible chimeras or five versions of a map across a dozen beta builds, things that never existed but in my mind can hold all the happy memories of heroic saves and hilarious defeats. This corridor from v1.04, that room from 2.0 when you could block it with turrets… I might try to draw some out on paper to see what they even end up looking like. Ghostly layers of architecture.

Alec: I’m going to be Shit Paxman and repeatedly demand that you reveal one level you love above all others, even though that is entirely the opposite of the reason you are particularly fond of particular games.

Alice: Mr. Meer, this line of questioning is-

Alec: ONE LEVEL.

Alice: NS_Eclipse from Natural Selection, maybe. Urban2 from Action Quake 2. All of Dark Souls except for the sectioned-off Anor Londo. I can't deal with this kind of pressure. No, okay, it's oh yeesh

Alec: So long as it has a chiptune soundtrack it’s your best ever, is what I’m hearing here.

Alice: When did things get so turned around that YOU'RE bullying ME? I'm never drinking again. Anyway, it's Hell's Kitchen from Deus Ex.

Alec: Tell me why now or I’ll make you write a feature about it next week.

Alice: We've had this discussion before. To me, Hell's Kitchen is the level that makes Deus Ex's promise. You wander around, poke into places, find completely optional doodads, hang out in a bar… it feels the most like a chunk of world from all Deus Ex, and you're just getting the skills (and skill points) to really have fun with that. Also, it's got a lot of verticality, which too few games are willing to play with. Getting up on rooftops, knowing you could be down in the streets or in another sewer, is great. I like surveying lands from high up. Let me on more roofs. I'm very sensible.

Adam: That’s why you love Assassin’s Creed so much. Best level - UBILAHNDAN.

Alec: I can’t believe no-one’s asked me what my favourite level is.

You’re denying the world the insight it so desperately craves.

Alice: Aren't you the moderator? I think it's your duty to ask yourself.

Alec: Who moderates the moderator? I need an adult.

Anyway it’s Xen from Half-Life 1. It’s actually the Tentacle Beast from Half-Life 1, but I’m going to say Xen anyway because it’s really bloody interesting despite being a nightmarish descent into fiddly platform hell. If it weren’t for Xen, we wouldn’t be anywhere near as misty-eyed about Half-Life as we are. Imagine if Half-Life ended with a bossfight inside Black Mesa. Imagine even if there had been another four or five hours of increasingly routine monster-murder and falling off ladders in Black Mesa. We’d have tired of it. Instead, it’s become this perfect thing in our minds, because we know that in its final leg it takes this abrupt deviation into something stranger and with completely different disciplines, and oh so much falling damage. It provides an honest-to-god-conclusion and it keeps what came before all the more special.

Also the giant spider-testicle is a hugely memorable, really unsettling and shocking boss fight. You’ve barely collected your wits after plunging into this new world, and then you have to battle this enormous, awful thing without any idea whatsoever what’s going to happen next or where the hell you can go, whether there’s ever going to be any more ammo or even what the context of your violent actions here is. In terms of preserving - even reinstating - Half-Life’s mystery and uncertainty, Xen’s a masterstroke. It’s so brave in its willingness to destabilise the player after so many hours.

But the Tentacle beast is so much better because it’s level as bossfight, environment and enemy and puzzles completely entwined, and I have written about that too many times before.

Alice: Xen is a magical end to Half-Life. It's a shame it comes with a whole new game to learn, but hey, that's alien worlds for you. Stabby meat trees! Flocks of strange birds! Vast lakes with horrible, horrible inhabitants! The shy plants were my favourites. Half-Life came at a point where technology could make really crude yet really exciting oddities teasing where games might go. The answer is a grey city, obvs.

Alec: Yeah, that’s it, it was Valve going “we genuinely believe we can make blockbuster science fiction with these huge, unpredictable setpieces, unexplained implications and dramatic shifts” as opposed to “this is how games go so la-de-da, no-one expects anything more than that, so here’s a big man in a tank to fight for a bit.”

Adam: I don’t disagree with these sentiments but I do love a good grey city. In games, and level design in particular, I tend to value the credibility of a place very highly so a really convincing but essentially mundane building, street or field is more exciting to me than a weird and wonderful place that doesn’t feel quite right.

Alec: I guess I might say Euro Truck Simulator 2’s depiction of Swansea, with that in mind. Now there’s an authentically grey city for you.

Adam: We could go back to Dark Souls (we shouldn’t because time is linear and irretrievable) and talk about how the world is weird but feels functional. It’s sensible.

Alec: I do notice that we’ve almost exclusively talked about shooters when we talk about ‘levels’. But we’ve also conflated it with ‘maps’ which is kind of its own thing.

Alice: OH HECK WAIT NO IT'S THE FOREST FROM THE PATH

Adam: Outside shooters, if I could remember precisely which level it was, I’d go with one of the Desert of Dijiridoos levels from Rayman Oranges but as it is, I’ll just say the entirety of Rayman Oranges.

Graham: Levels and maps are the same thing, sez I. Who makes maps? Cartographers? No, it's level designers. But I do like N+'s Pit of Despair and Vini, Vidi, Vici from VVVVVV. Or every level the algorithm produces in Spelunky. Maths, that's who makes maps.

Alec: The cornfield in X-COM is another very special one for me, though I guess that’s more level theme than level itself. But I can’t see those squares of yellow stalks without my blood chilling, both at the fear of what might be lurking in there and the knowledge that I’m about to spend forty minutes peering into corners of darkened barns to find the last Sectoid. As a statement that “something terrible has arrived in your pleasant world” it’s so iconic, though. Low tech conveying the sinister perversion of the human idyll so very well.

Adam: Dungeons too! Dungeons are levels and people can make maps of those levels. The second and third levels of the original Dungeon Master are imprinted on my memory. Terrifying places that seemed so unknowable at the time. I drew them on graph paper and wish I still had those old schoolbooks they were in.

Alec: Anyway, we all agree it’s that one with the frogs from Daikatana, right?