Bioshock's Ken Levine Talks Stories, Systems & Science

The Unreliable Narrator

As if we hadn't already heard enough from the man who steers the Irrational Zeppelin through developmental waters, Jim also had a long chat with Ken Levine, the creator of Bioshock and Bioshock Infinite. Read on for thoughts that span the sadness of cholera, the mystery of condiments, the joy of turn-based historical war, and some stuff about a game set in a flying city.

I've marked out some mild spoilers towards the end of the piece. These are non-specific discussions of the plot themes, but you can decide whether to skip.

RPS: How are you?

Levine: I'm terrific. I'm off today and I'm playing Unity Of Command, so... what could be better?

RPS: Sounds good!

Levine: Have you played it?

RPS: Yeah, I played it a bunch last year. It took me a little while to figure out how the supply-lines and stuff worked, but once I had that in mind it was fantastic. I only grabbed it to have something to play on my crappy laptop, and then I was amazed by how good it was.

Levine: I really like it. I've played all the campaigns and I am replaying them now. It's a really interesting game, and I am getting the point where I understand it well enough where it's hard for me to lose, but that's very rare for me in strategy games. I am not a strong strategy gamer, but this makes sense to me. I really dig it.

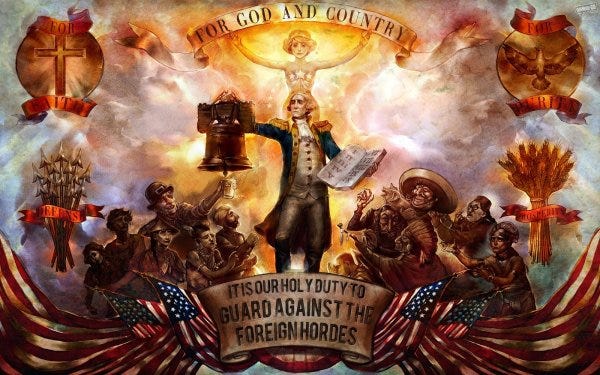

RPS: I know the other strategy guys at RPS had a blast with it, and it's been awesome to see more and more of those smaller games just having some design quirk that really makes them engrossing. Or having really lo-fi production and being utterly absorbing - the past two years of RPS seem like a catalogue of that. Anyway, we should probably talk Irrational and Bioshock stuff! So... my first question is about how games take sort of local and native mythologies and then create really authentic settings and atmospheres with them – I am thinking here of STALKER and its use of Chernobyl and related mythos – you seem to be doing that with American history and philosophy from the era the game is set in... I know you did a lot of research for that backdrop... has that been successful? Do you think you have made a success of using those ideas and themes in a game?

Levine: I don't think I would gauge success here as historical accuracy...

RPS: No, but as a theme...

Levine: At the end of the day I don't view myself as a historian, I would put that way, way down the list from game designer, I am just not that guy in any shape or form. But I do gauge success on whether it makes the experience better as a game. There's no secondary purpose, it's about making an entertaining experience for people, and whether it's for me to judge that... well, it's really down to each individual person playing it to judge that.

However, I do feel like “history nerd gratified” that we got some of the things in that we wanted to get in. We dealt with Exceptionalism, we dealt with quantum mechanics, we dealt with the music of the period, we dealt with the cultural and class movements of the period, and that's all gratifying to me because I get to work on stuff that I am really interested in. And I need that. If I was put on a Dora The Explorer game I would probably have a tough go of it. Nothing against Dora The Explorer, of course, it's just not my field of interest. I wouldn't bring much to the table. I've had that experience, too, with Tribes Vengeance. I didn't feel like I was a good guy to write that story, because I didn't have as much of a connection with that franchise as I needed to. Whereas, when I worked on System Shock I was hugely connected with that game as a fan, so I had a lot to say. And that's true here, too. Whether or not people think what I have to say is interesting is a secondary issue, but I do have a lot to say in this space, because I am interested in this era and these themes.

RPS: Was it you who recently said that as a dev you were interested in telling stories, but as a player you were more interested in systems and emergent stuff?

Levine: That was me.

RPS: How do you reconcile that? Do gamer Ken and developer Ken fight at all?

Levine: No, they don't fight. As a professional game developer I enjoy one type of work, and as a gamer I enjoy another – like I said, when you called I was sat here playing Unity Of Command, and you'd probably have trouble finding a game as far away from Bioshock Infinite as that. It's about supply lines! It's very different from what I do. And, you know, I have insomnia, so I've sat up every night for the past six weeks and played Unity Of Command. That's weird, right? For someone like me? And when I play a narrative game I will skip a lot of the cutscenes... is that weird? I guess it might be, but it's just the way I am. And that's not to say I don't enjoy narrative games – the first System Shock was a great narrative game, which was why I was so excited to work on the second one. And I liked Beyond Good & Evil, and Limbo was a really good narrative experience, the Half-Life games are great narrative experiences. There are bits and pieces that I enjoy, but the games I tend to end up playing for great lengths of time tend to be more about systems.

RPS: Do you not think though that because games as a medium are omnivorous in terms of what media they are composed of – they will mix music, history, interface design, architecture, even performance or sportsmanship – that game designers have to have a broad range of influences if they are going to make interesting games?

Levine: It benefits any person, any person at all, to have a broad range of interests. Game maker, writer or construction worker, whatever. It adds to your life. I'll meet someone who works in insurance and ask them thirty questions about working in insurance, because I like figuring out how things work. I read a lot of history, sure, but I read about how cities get built, like last year I read that book about... oh, the disease that gets carried in the water?

RPS: Dysentery?

Levine: No, it's one where...

RPS: Cholera?

Levine: Yes, cholera – everyone thought it was a miasma in the air, and some guy who tracking who got sick managed to figure out that it was coming from the wells. He realised that people were getting sick next door to someone who was perfectly healthy, and the reason was that they weren't drinking from the same source of water. But that book is actually about the development of the scientific method...

RPS: Is that The Ghost Map?

Levine: Yes, that's it.

RPS: I bought my mum that for Christmas, and she got a lot out of it. Although she said it was pretty depressing!

Levine: Haha, well it is pretty depressing, but it's also really exciting, because it's about one guy, using science - in the face of all these embedded forces who thought they new the answer to what is going on - to help people. That was the beginning of the end of cholera in the Western world, and it showed the freeing power of science, which makes it a great book... I am going off the beaten path here.

RPS: Well, it seems like one of your main themes is sort of rationality versus dogmatism, and how reason can go haywire, so it's not unsurprising that you are interested in that sort of thing – and really isn't the history of ideas actually just as thrilling as the history in terms of events?

Levine: Do you know Bill Bryson?

RPS: A little.

Levine: You should read At Home, because it's about the conditions that made our homes as they are. Like, you have salt and pepper shakers on your table – how did that happen? What caused those two condiments to be on your table? Things like that. Why do people have living rooms and bedrooms and not something else? I recommend that highly.

RPS: Okay, so now I have to come up with a question that connects to that somehow. How about this: I was just watching one of the early gameplay sequences you released for Infinite, and it was the one where Elizabeth has just been abducted and Booker is heading off to find her, and the camera or player is dwelling a lot on the architecture, which is something I do myself. But my question is really: do you owe more to the history of architecture and design than other games? Are your games more about architecture than other games?

Levine: Well, look, any game that has a building in has some reference to the history of architecture. But I think what you are seeing is that our games tend to build a monoculture of a particular style, and you don't tend to see that. Very few cities have a particular style that dominates – although actually where you are in Bath, as a city, it probably has more of one type of architecture than most others, because of when it developed, and that probably has laws protecting it -

Levine: -but most cities, look at LA or Boston, you will see thirty different styles out of the window. In Rapture almost everything is Art Deco, there's really only a couple of styles, and so you see a consistency there that heightens the importance of the architecture. You are not seeing a melange, you are seeing a monoculture. Our people, Scott Sinclair, Shawn Robertson, and Jamie McNulty and everyone else here on the team have a huge interest in architecture and getting it right. When 38 Studios closed their misfortune was our fortune because we were able to hire a guy whose job became taking our buildings to fix them, and Scott, well, he created style-guides and colour-guides, and it really changed the spaces. He did a lot of research and he did a lot of architectural plan style treatments to help us get there.

RPS: Do you find you get a lot of architects in level design?

Levine: Well, perhaps more among the artists – we split it up to have artists making the spaces and level designers turning them into actual playable levels - but I think in the way that I am an amateur history nerd with have amateur architecture buffs who are just interested in getting it right. People who have an eye for these things, and understand what makes them work. Scott Sinclair and I were talking about an certain aspect of architecture yesterday, and discussing how we get across to newer members of the team what it's really about. In a game, especially, there's a lot to figure out. I went to the Rockerfeller Centre in New York when realised we wanted Art Deco for Bioshock, and my wife and I went around with little tourist cameras taking photos of doorknobs and lighting, and so on. You start to understand what made that movement what it is. How do you represent that in a game? If you fall into the tiny details the gamer won't see it, and you have to distinguish what is essential to the real structure from what is essential to the player's understanding of it in this macro-space. Obsessing over tiny screws that might be fundamental to a real space won't work.

RPS: Later along the line in development, then, do you find yourself then seeing ideas and images you've collected appearing in the game world?

Levine: Well things like that little tour I took of the Rockerfeller Centre are the early stages, because there's a tonne of work, a tonne of research, and there's seldom a one-to-one transition to the game. You end up trying to capture the essence or the spirit of something, rather than literally recreating it. But often you will see something a designer or artist is working on, and it doesn't feel right, and then you have to figure out why it doesn't feel right. And that can just be because it contains a couple of elements that you would never see together. I remember working on Thief, or at least I think it was Thief... anyway, I was looking at all the doors in the game, and all the doors looked wrong. I didn't know much about building, and it took me a while to realise that there were notice that there were no frames – you don't just cut a hole in a wall! There's a frame there for the door to go into. And we have a hard time noticing that stuff sometimes. Most of us spend our time looking at screens or our loved ones, not a seams and moulding and flanges, but nevertheless when they're not there we can see something is wrong.

RPS: But it's not just architecture, is it? A city is also people, and Infinite seems to have a lot more work there, which puts people in the world, getting on with things, rather than the constant antagonism of Rapture?

Levine: Rapture is a graveyard, for the most part. That gave us lots of licence as a game maker to not do things with the game that we would have to do for a city that feels functional and alive. We resisted it for a very long time on this game – we were dragged kicking and screaming into all these things which were really hard to do, just by the fact that we realised that the game needed them. At first we didn't have a character who spoke, then we didn't have a companion character, and then the companion character was mute, and then we still had a dead city... but we couldn't do that again. We kept pushing ourselves further and further. We pushed ourselves out of our comfort zone. And each of those things ended up being an amount of work that I don't think we comprehended. Our instincts were telling us “watch out!” but we didn't really do the math on that.

Have you got to play the first couple of levels?

RPS: Sadly no, although to be honest I had been avoiding doing anything other than catching a few videos, because I really wanted to come to it unspoiled.

Levine: You're actually in good stead with just the videos – the video from a couple of years ago doesn't really represent the story – but there is a good chunk of the game where you are just walking among the people. That proved to be very, very difficult to do. And I think that's one reason why people are reacting quite as they are, because it feels so different to Rapture in that sense. It really gets you more of that “slice of life” feeling, but boy did it make our life difficult.

RPS: Was that the hardest thing you had to do on this project?

Levine: Probably that, yes. Or maybe Elizabeth – and that's sort of an extension of the same problem. It's a living person who is always around you. With Elizabeth your expectations increased – we knew that the moment you turned to her and saw her blankly staring at the wall, you'd lose the plot with her. I'm not saying we succeeded a hundred percent of the time, but the team do a great job of keeping her engaged, and making her feel active and a part of the world all the time. That wasn't just technology work, it took a lot of study: what do people do? The player can sit there doing nothing for ten minutes – what do people do when they're waiting for ten minutes? When you are fighting enemy AI there's a lot of nonsense we as developers can get away with, but when you are just hanging out with them it gets way more complicated.

[MILD SPOILERS]

RPS: So Elizabeth and her reality tearing powers... I guess that has something to do with the exploration of quantum physics exploration you mentioned earlier? What were you actually trying to explore there, or is that a major spoiler?

Levine: Okay, well, this is a little spoilery, so if you are worried by that stop reading right here! But Elizabeth's powers are tied into the idea of there being multiple universes out there.

This was the time period, around the turn of the century, when scientists like Einstein, Heisenberg and Planck began moving away from the Newtonian view of the universe which was very deterministic. When they started poking at this idea and doing the math, they realised that the universe must be a much more complex thing that we thought, and we had the rise of observations such as a photon being a wave and a particle at the same time - two mutually exclusive concepts to our traditional way of thinking about the universe - and that was the beginning of notions like Many World Theory, because how does this one thing exist in two mutually exclusive states at the same time? In the same way that in the era of Bioshock 1, Crick and Watson were just starting to get their heads around the structure of DNA, and we took that and ran crazy with it, well, we're doing something similar with these ideas in Infinite.

RPS: That sort of multiple reality multiverse idea gets a lot of play in literature and fiction these days, and I think that's because it's super exciting for writers, because it suggests a sort of concreteness to the imagery they play with, and perhaps that the barrier between the real and imagined is quite thin – was that the sort of thing you were thinking? And was it exciting to play with those ideas when you were writing the characters and plot?

Levine: Yeah! I came up with the concept and decided that I wanted those to be Elizabeth's powers, and it then took a while for us to define exactly what that meant. But also I wanted those powers to be central to the plot of the game. It was exciting and fun because, for the writing team, it was one of the hardest things we had to plot. As an individual writer I know, well – I wrote almost all of Elizabeth and Booker's dialogue and those interactions – trying to get that stuff across in the context of a videogame, and have it work on a metaphorical level, well... If you watch Back To The Future the doc takes out a blackboard and starts explaining things, and fortunately Christopher Lloyd is actor enough to pull that off, but it's true of so much: the character who explains things, like The Watcher in Buffy The Vampire Slayer, he's there to explain everything. That's really hard to do well in a videogame. I think the way we do it is to stretch it out across the game and make it very visual, build up to it. We add a little bit of information at a time, don't dump it. So getting those ideas across was one of the toughest things we had to do, but it was also one of the most exciting, particularly when you've finished it.

There's a saying, something like... “It's terrible to write but great to have written!”

RPS: A few people said, having played the first few levels at preview, that they felt Booker might be an unreliable sort of character... can you say anything about that? Are you dabbling in that area of unreliable narration again? A player-character that the player can't trust?

Levine: If you've seen the first five minutes video you'll see that there's a quote on the screen that implies pretty much exactly that. You come into a Bioshock game, and that's not going to be too much of a surprise. You are expecting something to be going on. Whether Booker is keeping information from you that he knows, well, that's a separate issue, and I think that would be an uncomfortable place to be. I wouldn't say that about him. His perception of the world and the player's perception of the world might have some challenges. I don't see any reason to be coy about that – people are coming into it expecting that, and the question is really how and why and what does that mean? The question of unreliable narration was one of the big reveals of Bioshock 1, and it's very different here, and serves a different purposes, but it is there and we fess up to that pretty quickly.

[/MILD SPOILERS END]

RPS: Why did you have a talking player-character? Is the silent FPS protagonist over-used? Could the talking character end up annoying players? (See Far Cry 3...)

Levine: Oh, yes, and we spent a lot of time revising Booker's character. Not his personality, but how he expressed it and what he said. You don't want real tension there, you don't want the character to say something really extreme that you can't get on board with and decide it's time to shut off the game at that point. But we need people to buy into the experience – which is why you don't want the character to know significant stuff that the player does not. You don't get up in the morning and read out your autobiography to figure out who you are, and in the same way stuff comes out about Booker's past in an organic way. Whether we did that successfully will just be down to the gamer to judge. I am pretty happy with it.

The reason we didn't have a silent protagonist is that we kind of made that difficult for ourselves with what we did with Bioshock. A large part of that game was about the fact that he was a silent cipher, and what that meant. Once you had done that, and you've shone a light on that, it becomes tough to come back from. Because then if there's a silent protagonist a second time people will either expect to find out a similar thing about this character, or alternatively “oh you just guys forgot about everything you said in the first game about being a silent protagonist and taking orders from a third-party, huh?”

And that's a similar issue to the city – I don't want to call it a “living city” because to me that means like GTA or something, which this isn't – but the Columbia in which there is activity in, we had to do that or we'd end up repeating ourselves with that dead city. Bioshock Infinite was a much more challenging game because we had made Bioshock. If we hadn't made this as a Bioshock game maybe we could have had the dead city and the silent protagonist. But it is, so we had to move on.

RPS: Just touching on that idea of unreliable narration that Bioshock dwells on – games generally tend to be quite literal, don't they? I'm trying to find the best way to express this, but I was thinking about how books or movies are so often tricks, or illusions, or sleight of hand, whereas games are so often just what they appear to be. Are you trying to avoid being over-literal in that way? Whether or not you regard the Bioshock games as successful, are they basically exploring the idea of making games a little less as they seem?

Levine: I have this friend from a D&D group in high school, he's a writer named Andrew Mayer, and after we had both seen Inception he made a really interesting point about the ending. We were talking about that final scene where the camera cuts off before the spinning top either falls or doesn't, and that leads the audience to wonder if DiCaprio's in the real world or not in the real world... And Andrew says to me: “No, he's in a movie.” And I thought that was really interesting. I don't know if that's what the authorial intent of that scene was, but it's interesting to notice that DiCaprio's character is never either in the real world or in the Inception world, he's in a movie. If you step back from it, neither is more or less real than the other. But on an emotional level that's not true for us, we think that the movie's real world is more real than the dream world. Some things in fiction are more true to us than other things. In Bioshock Jack's perception about himself is no more or less real once Andrew Ryan told him the truth about himself, because it's all a lie. It's all fiction. Except it's not.

I love that stuff. I have a bit of the post-modernist bent to me. I grew up loving Tom Stoppard, The Manchurian Candidate, Fight Club, Twelve Monkeys, Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind... you know, stuff like that where the form itself is part of the conversation, where identity is a question, where the form itself is a question. Some people are capable of doing that really elegantly, and I've always enjoyed that kind of stuff, because it's not about twists per se, but about your perception of the experience and what you take from that.

That's why I love my friend's observation about Inception, because there's no more validity to one than the other. There is no spoon, right?

RPS: Haha, that would be a great point for us to close that interview, I suspect, with... profundity?

Levine: I guess quoting The Matrix is what passes for me being profound! [Laughs]

RPS: Thanks for your time.

We did actually continue our conversation from there, but that will appear in another article. About other things.

Bioshock Infinite arrives on March 26th.