IF Only: Apocalypse Eve

Choices at the end of time

Apocalypse is a popular topic of IF. Brian Moriarty's Trinity explored the threat of nuclear annihilation, back in 1986; Phantom Williams' 500 Apocalypses got several mentions here last year, from me and from Philippa Warr. Max Kreminski's Epitaph takes a more Spore-like approach, as you're allowed to try to nurture procedurally generated civilizations to survive longer than a few turns, and instead (most likely) rack up an impressive collection of failures.

Whatever kind of apocalypse you're trying to model, interactive fiction probably has something to offer. Here are some of the most interesting.

There are of course plenty of zombie apocalypse games in the IF canon. Jim Dattilo's Zombie Exodus is popular with Choice of Games fans; Mike Ciul has parser IF fans covered with A Killer Headache. Quintin Stone's Scavenger presents a more thunderdome-esque version of the shattered future, while Jason Devlin's Vespers is a plague narrative, the past's idea of what the end of the world might look like.

A lot of these are adventure stories or survival stories. Everything is really bad: what will you do now? Or they're socio-political explorations of some kind. The post-apocalyptic genre imagines that life will go on, even after a cataclysmic event; that it's possible to escape or salvage something for oneself. Often they invite us to imagine completely different ways of ordering society. Occasionally — as with Fabricationist DeWit Remakes the World — they're actively hopeful.

But the properly apocalyptic game admits the possibility that life won't continue. It focuses the player tightly on a handful of choices or a few hours of storytime. The end of the world is here and cannot be avoided. In this context, what do you do? What are your final priorities? What are you even paying attention to? It's an excellent context for the reflective choice, a decision that gives the player options but never shows consequences, because the only possible consequence is how the protagonist feels about what they are doing.

Queers in Love at the End of the World (Anna Anthropy, Twine, 2013) is the tiniest and most focused example of this. The piece is limited in realtime: you only have ten seconds to decide what you will do to say goodbye to your lover, so little time that it is hard to read all the text before it is wiped away in a blink:

The scope is too small for profound rethinking, but the story does capture the sense of focus that comes with great danger.

Before the Storm Hits (JY Yang, Twine, 2016) gives you a list of tasks to do before you leave the planet: something terrible is about to happen, and there are only so many tickets to the off-planet launch. You don't have much time left to gather your things and get there.

You can choose any order, but you can only do three of the tasks on your list. You'll want a different approach depending on whether you're trying to save yourself, or save someone else, or bring your relationships to a positive conclusion. Trying is the operative word here.

Perhaps the most striking thing about this piece is how it demonstrates the function of context. The same text can carry a very different weight depending on what you've done up to that point, and what you know when it comes. The same sentence about waiting for a friend can seem naive, loving, or intensely deluded.

Prospero (Bruno Dias, hypertext using Raconteur/Undum, 2015) recasts Edgar Allen Poe's The Masque of the Red Death. A plague is consuming humanity; a wealthy prince has locked himself into quarantine with a group of fellow revelers, and they are trying to outlast the oncoming death.

This version casts the player in the role of the Red Death, coming to rid the place of the prince and his ridiculous, truth-denying advisors. There is a little latitude — here and there, some ways to spare rather than destroy, if you're so inclined — but mostly you're there to enact a wrath and a punishment. Anger is a recurring theme in Dias' work — anger against the rich and powerful who keep everyone else down; anger against the grind of capitalism. Some of his other work explores the reasons more deeply, but Prospero focuses simply on the implacable destruction.

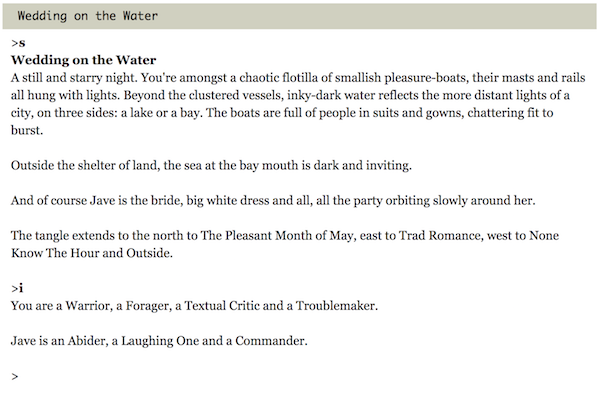

Invisible Parties (Sam Kabo Ashwell, parser, 2014) is a longer and more puzzle-focused piece than most of the others on this page. Here you are at a sort of supernatural party, in which each room represents a different form of the ending of the world; all these apocalypses have been lashed together like the boards of a raft.

Somewhere in the mix is your lover Jave, but you have a hard time tracking her down and talking to her, because the environment you inhabit is a tangle of space and time where the usual rules have been misapplied. What you can do: use your and your lover's particular personality strengths to shift the social environment towards destruction. There are no locks and keys in this game, no inventory management. Instead you'll find yourself using gifts like Commander, Troublemaker, and Textual Critic.

As you pass through the environment, you're destroying some rooms and opening others. It's possible to lock yourself away from Jave, or trap yourself in the wrong part of the map. This is a maze puzzle of sorts, not because you are lost — all the directions are straightforward and all the rooms are distinctly named — but because your destructive influence makes walls out of doorways, and you want to be careful how you do that. (It may help to know that the game's cover art is in fact a little map, with all the connections marked.)

It's possible to get a positive ending out of Invisible Parties — but there are a number of scenarios where you will end up trapped. In most IF games, it's frustrating to reach a point where it's no longer possible to win, but in Invisible Parties that's an important and valid narrative strand.

[Disclosures: Emily has met Anna Anthropy and Brian Moriarty. Sam Kabo Ashwell is a friend of hers, and after the first release of Invisible Parties, she contributed some bug reports incorporated into the final version. More generally, Emily Short is not a journalist by trade and works professionally with various interactive fiction publishers. You can find out more about her commercial affiliations at her website.]