IF Only: Games of Mystery and Discovery from IF Comp 2016

Assembling evidence

IF Comp 2016 is still running, and I'm back to suggest a few more possible highlights if you're interested in trying out the games. I am not going to have a chance to cover nearly all of the 58 entrants in this column, though, so I strongly encourage you to check out the site, pick out some games that interest you, and possibly even vote. Voting is open to anyone who has played at least five entries.

This time I'm looking at a few of this year's IF Comp games that — in very different ways — invite the player to explore, discover and piece together a narrative.

Color the Truth (Brian Rushton, parser-based). Color the Truth invites the player to investigate a murder by (as typical for IF) examining various environments and also (less typically) by interviewing various characters. When a character gives you a statement, you play through a sequence as that character, getting to see the environment and suspects from their perspective. But sometimes, of course, characters lie.

This is where interrogation comes in. The game keeps a topic inventory for the player that tracks everything you've learned so far. When it seems as though two conversation topics have a bearing on each other, you can actually LINK one topic TO another, crafting a third line of inquiry when you discover some point of contradiction between things you've been told. (In this respect, the mechanic is a bit reminiscent of Contradiction, minus the incredible hammy acting.)

When you've caught someone in a lie, they'll give a new version of their statement, which you play through again. By the time the game is over, you'll have played through the events of the murder multiple times from the perspectives of each of the major characters. It's a pretty effective way of letting the player pull together evidence and conflicting information.

*

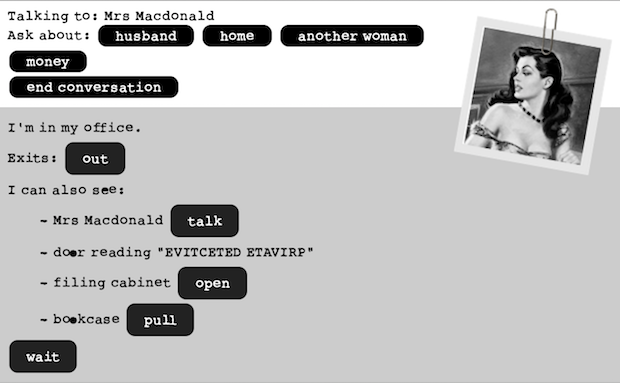

Detectiveland (Robin Johnson, choice/parser hybrid). Of the games on this list, Detectiveland has probably the most conventional design when it comes to revealing information. It puts you in a standard gumshoe role: the shabby office, the revolver, the hooch, the cases brought to you by untrustworthy dames, and lets you solve some puzzles to figure out what's really going on. The game actually offers several different cases to solve, each pretty short and punchy; but there's enough of a modeled world there that you can if you choose wander around in between cases and get a sense of the town you live in.

At the same time, the game steers clear of the "and now what?" sensation one sometimes gets with a parser-based interactive mystery. The game engine is one of Johnson's own invention: it has a lot of the same world model features as parser interactive fiction, but the interface offers buttons for all interactions, which means that there's less chance of getting really stuck. That doesn't mean that all the puzzles are transparent, though. For one thing, there are quite a lot of locations in this town. For another, some actions, even on objects in the same room with you, appear only if you're wielding the right inventory item. (So you can't just possess, say, a matchbook in order to light something; you have to actually have it as the item in your hands at the moment.)

At least for me, the result was a very natural-feeling blend of puzzle-solving and hints. Just occasionally when Johnson wanted to give the player some whimsical options, there was no difficulty feeding in those odd alternate verbs. The multiple UNDO option makes timed action sequences a lot easier to cope with, too.

Overall: silly, noir-themed goodness that never takes itself terribly seriously. The presentation captures some of the appeal of a parser, but with the accessibility of a choice-based game. If you enjoy the style of user interface, you might also like Draculaland, Johnson's similarly designed vampire adventure.

*

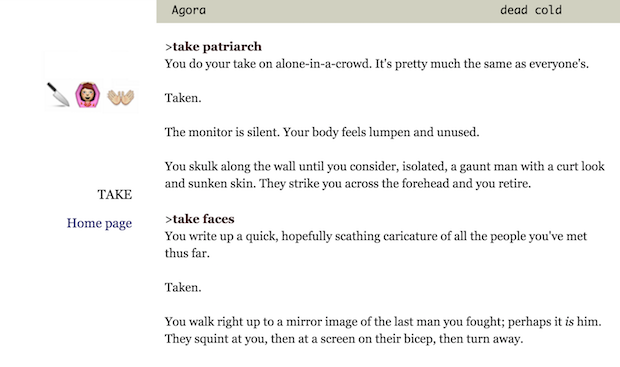

Take (Amelia Pinolla, parser-based) runs away with the classic parser verb TAKE. In this story, you can only TAKE things — EXAMINE also works but isn't obligatory, and pretty much all of the rest of the standard parser vocabulary is shut off, making this an extreme example of the recent trend towards simplified parser designs. But here TAKE means to write a hot take on: to find more and more emotionally or politically juicy ways to describe and present your environment for the entertainment of a demanding and not particularly sympathetic audience.

The game is unrelentingly bleak about this process. The protagonist is serving up more and more painful parts of her psyche for the benefit of onlookers who really couldn't care less; everything she suffers, as a gladiator, as a participant in feasts, is about making herself a spectacle in different ways in order to earn the sufferance to keep living. Sometimes, she reflects on the spectacles of other things and other people:

You write about the strange appeal of women in dank grottos. Back home it was an entire subgenre: women draped over sewage, always in some sort of ethereal flowing gown, as if simultaneously growing and wilting. You stretch out a bit to illustrate the pose.

The trick is, of course, the player's role in all this is as the curious onlooker attracted by all the paraphernalia of the protagonist's life. We're commanding her to do takes on these things because we want to make progress in the story, perhaps, but also because those are the particular items of most interest (possibly prurient interest) to us as readers.

*

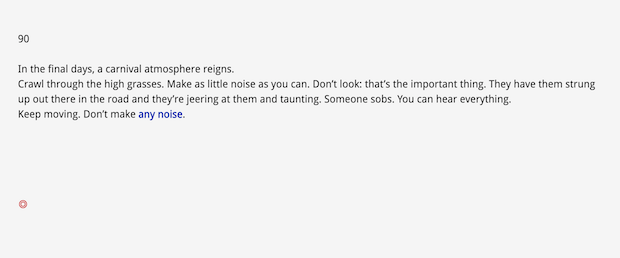

500 Apocalypses (Phantom Williams, hypertext) is framed as an exhibition about past apocalypse and societies that have been destroyed. The piece consists of 500 brief vignettes about different ways the world can die: a growing apathy in the population. A forest that grows and grows over civilization and that cannot be fought back even by the continuous efforts of a forest-fighting team. Sometimes the vignette is briefer and more personal than this, looking just at a single person or a single family facing destruction. It is unsurprising to find a wealth of startling images here, especially if you're familiar with Summit, Williams' contribution to the 2015 IF Comp.

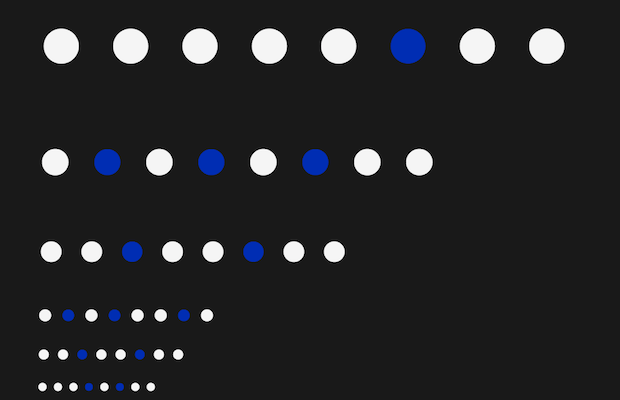

Some of the apocalypses link to one another thematically: a noise in one, connecting to a noise in another. But there is also an overview structure from which you may access any of these vignettes: a gigantic field of patterned dots, some of which are links down to the vignette layer. Here is just a small section of that field: the blue dots are links that I have not yet explored, vignette links I haven't opened:

500 is a lot of endings to read. Although each passage isn't very long, the vignettes suggest — perhaps require — a bit of thought, a bit of time to construct a context around them that makes sense. The dot-field representation of all these elements suggests that there is some kind of priority and hierarchy, that the early apocalypses are the big important ones and that later on come smaller tragedies, or at least ones whose significance dims a bit.

I found myself thinking of Barbetween, an IF work designed as a multiplayer space in which players could leave small inscriptions about times that had been bad in their lives. Both 500 Apocalypses and Barbetween hint at the grief/consolation of realizing how many different sorrows and kinds of sorrows exist in the universe.

Your mileage may vary, but I found that this worked best for me when I approached it — both in reading and interpretation — the way I might approach a book of poetry. I allowed myself to dip in here and there. I gave myself permission not to read the whole thing and not to read it all at once. The FAQ for the piece explicitly invite you to do this. They also invite you to write your own apocalypse and email it to the author. I have not tried that, but it fits. It's hard to say how long I will spend with this piece before I feel I am done with it.

*

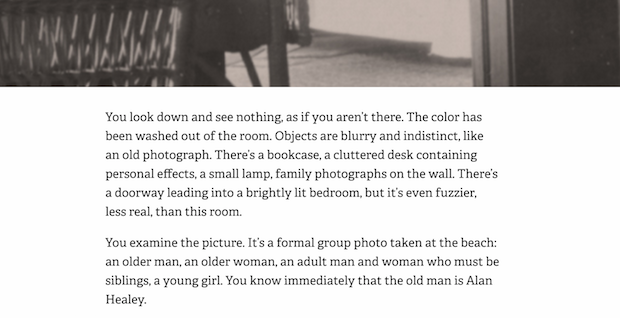

Stone Harbor (Liza Daly, hypertext). Stone Harbor tells the story of a sidewalk for-entertainment-purposes-only psychic who finds himself dragged into a police investigation requiring genuine powers. Stone Harbor uses its interactive aspects sparingly, more to direct attention and focus than to give the player control over narrative direction. The story is fairly linear, with long passages of uninteractive text, but I found that the pace worked well for me, and the interactions focused on critical beats of the story.

Your protagonist's powers involve the ability to "read" from physical items, and — appropriately — much of what you're doing as a player is selecting one of several physical objects to focus on. Confronted with a stranger, are you likely to find out the most about him from his wedding ring, his watch, his baseball cap?

Your choice typically doesn't change the course of the plot much as far as I could see, but it does control which character information you gain when, and which perspective you take on the participants in the drama. Effectively, it's an approach that asks the player to do a cold read, just as the protagonist routinely does: which of the objects currently in your line of sight is likely to take you to the most emotionally interesting beats, the things you're most eager to evoke and talk about now?

The presentation is beautiful. Text spools out as you play. Chapters are set apart from one another with chapter-heading images that evoke the locations in the story. It took me less than an hour to read.

[Disclosures: Emily has stayed over at Liza Daly's house and done some work with her in the past. She has also met Amelia Pinolla. More generally, Emily Short is not a journalist by trade and works professionally with various interactive fiction publishers. You can find out more about her commercial affiliations at her website.]