A year in Stardew Valley: life, labour and love

Still life

Paul Dean spends a year in Stardew Valley [official site], ahead of the game's one year anniversary later this month, and reflects on the work that goes into building a life, virtual or otherwise.

The farm I’ve inherited is a mess. It’s nothing more than a small house at one corner of an overgrown tract of land, set away from a tiny riverside village of complacent, mostly white people in large, embellished houses. It’s springtime and I’m a stranger. As a welcoming gift, a local passes a dog off to me that I think is a stray they have no desire to deal with. The farm comes with a big old television set, a handful of cheap tools and a stagnant pond.

I’ve abandoned a pointless desk job in some soulless town and now I have no income. I have no friends. I have decided that this is my life now. It’s how I’ll come of age.

Or it’s how I’ll come of age in Stardew Valley, anyway. The real me grew up in neither a substantial town nor a tiny village, but instead in a sort of miniature suburban limbo, a featureless urban smear that existed to house commuters who worked an hour away in London.

Drive half an hour in one direction and you might actually find a farm, half an hour in another and you might find a building more than six stories. It was a compromise of a place that had no culture and no character. There isn’t much to do in town except drink. Later on, the area would be named and roundly mocked in the television show The Office.

We all laugh. It’s funny because it’s true.

A river runs through Stardew Valley, and it has beaches and mountains and forests that I can reach in mere moments. Animals wander in the wilderness and the seasons bring sun and snow. To someone from one of the monochrome urban pseudopods that oozed out of London, it seems like a caricature of Romantic-era landscape, somewhere too melodramatically pretty to really exist.

My first job on my farm is to clear space and make room for at least the smallest of plots. If I plant seeds I can grow crops, if I grow crops I can ship produce and if I ship produce I can start to make a living and, just as importantly, I can begin to take pride in what I have.

So, over the next few days I use some of the savings I have to buy seeds, I explore the village, the oddly named Pelican Town, and, following local advice, I also forage in the wilderness. Long before I see any new shoots on my own land, I’m tugging onions and radishes out of the forest floor and selling them for spare change. My life quickly becomes a routine of watering crops at dawn, foraging in the afternoon and using spare hours to beat back the ever-encroaching sea of grass and garbage that my dog bounds recklessly into every morning. The tools I’m using are terrible and, while a blacksmith in the village promises better alternatives, all the things he offers are expensive.

Everything in this village is expensive, whether it’s raw materials or rucksacks or even fishing tackle. My best bet is to chop my own wood, cut my own stone and, when the opportunity presents, fumble my way into the nearby mine and drive my pick into the walls for coal or minerals. All it costs me is time. Time and energy.

Managing those two resources isn’t easy. Making the best use of time means saving some work for the evenings and taking a break in the day to walk to shops and gather supplies. On more than one occasion I make the trip into the village only to discover the shop I need is closed for the day, or stopped trading at four. On a couple of evenings I simply collapse from exhaustion, unaware my body was so close to failing.

--

I’m sixteen years old and I’ve taken my first job. I work in an enormous hardware warehouse that sells everything from timber to plumbing supplies to electrical equipment to a hundred different types of flooring. Most of the time I will wake up at six in the morning to start at seven, to work shifts until mid-afternoon, constantly on my feet and often performing heavy lifting for customers. The floor is concrete and it’s not uncommon for my boss to forget to give me a lunch break until midday or one, so I stand on that concrete for five or six hours straight.

I demonstrate the apparently rare ability to be responsible so I’m given positions of seniority. I work with security or, in the winter months, I’m on a solo early shift in charge of the garden center. At seven, the sun isn’t up, so I’m working in the dark, sometimes the rain, and my breath comes out as clouds. It’s the middle of the nineties, so the minimum wage has not yet risen and I’m earning three pounds an hour. Since this is my first job, I think all this is completely normal.

The place does a roaring trade. It makes more than twenty million pounds gross a year, often taking a quarter of a million on a busy weekend. The managers are excited about this. They set targets. Today, they say, we’ll make a hundred thousand pounds. It must be true, because they chalk it onto a board. The managers don’t stick around, because six months managing a store that makes twenty million pounds looks really good on your CV and then you can go away and do something else. They aren’t very invested in developing or maintaining anything. Eventually, the store will overspend on its revamp and need to shed droves of staff.

Sundays are the busiest. We open at ten but, even half an hour before that, hundreds of customers are already lining up outside with empty shopping carts. They peer in at us, waiting for the doors to open, long lines of complacent, mostly white people desperate to take their chrome taps and wood flooring and succulent shrubs back to their large, embellished houses.

One of my colleagues looks out at them. “You’re so sad,” she mutters. “Don’t you have anything better to do?”

--

The first person I really meet in Stardew Valley is Robin. I immediately like Robin a lot. She is a practical, straightforward woman who does all the village’s carpentry. I find out she’s skilled enough to be able to expand the small cottage I’m living in, can build barns and coops for any animals I might want to take on, and sells timber and electrical equipment and a hundred different types of flooring.

It’s a nice idea, but barns and coops are expensive. Animals are expensive, too, and even if I could afford some I’m not sure if I’d have the extra time and energy to take care of them. My dog is all I can manage and that’s because all he needs is the space to gallop in long, unbroken lines, until he runs headlong into a fence.

Some weird local man (I don’t remember which and all the men are prone to oversharing) hints that I might meet someone special in Stardew Valley. There’s no option for me to say that Robin has already caught my eye, but I later find out that this is because Robin is married. In fact, she has a daughter who is already a young woman. Robin is married to Demetrius, who is the one person of colour in this village and who is really enthusiastic about science. He reminds me of the one person of colour in my home town, who was really enthusiastic about science.

The hours upon hours of hewing, hoeing and hacking have blended into days, the days have melted into weeks and my shoots have turned into plants. As soon as I can wrench them out of the ground and ship them away to be sold, I need to be planting even more, because farming is all about cycles. I clear a little more space and try to imagine the shape of the farm to come, how the fields should lie, where an orchard might stand, keeping the cones and acorns from the dozens of trees I’ve had to labouriously fell, day after day.

The villagers are talking about the new man in town. Sometimes they come out to see me, always one at a time, peering in, waiting on my doorstep. Some have gifts. Others have advice. They want me to visit. If only I had the time, I think, as I look at all the mismanaged land that needs clearing, hoeing and irrigating. On a free evening I might want to visit the local inn, but so often there’s still tasks to be done late and so I’m working in the dark, sometimes the rain. I suppose I could. There isn’t much to do in Pelican Town except drink.

--

I’m eighteen years old and everybody I know is going to university. I’m not. I didn’t get the grades I wanted, so though I still could go, I wouldn’t even know where. I don’t understand how university works. Nobody in my immediate family has ever been there and hardly anyone in my extended family has either. My parents left school in their mid teens, with no qualifications at all, and I remain as confused by the process many of my peers are going through as I am by their large, embellished houses.

If I stay at home I will have to work and pay rent so, at various times, I have jobs as an accounts clerk (a pointless desk job in some soulless town), a phone salesman (where the aim is to sell functionless extras) and a supermarket assistant. In the last job, I have to clean up a kid’s piss because their mother doesn’t want to. This is what you do, though, because the point is to have a job and earn money. Isn’t it? You have to be practical and responsible and pay your bills. The idea of a career doesn’t even enter my head, because this is a town with no industries, no major employers and almost no connections to anywhere else. If you don’t get out, you become stuck, and I wouldn’t even know how to get out. All I have is dreams. And those aren’t real.

Later, I have a job in a building that processes foreign currency. An astronomical amount of money is stored there, beneath multiple layers of security, and one day a couple of boys messing around run a trolley into one of the cyclopean safe doors, behind which tens of millions of US dollars are kept every night. They don’t know they’ve triggered a silent alarm until, four minutes later, a van full of police officers in riot gear burst in and point carbines and submachine guns at them. The boys are fired. We’re supposed to have this job because we’re practical and responsible. In a town without opportunity or ambition, even a little maturity gets you the best jobs. Of what jobs there are.

--

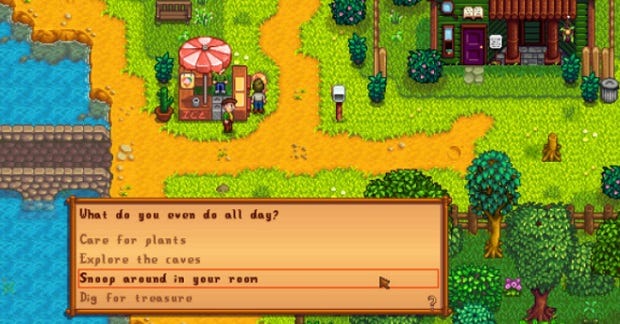

If Robin’s the first person I meet, the first person I really notice is Pam. She lives in a trailer by the river. I don’t know what Pam does during the day, but I know exactly what she gets up to in the evening. Pam sits on the same stool at the end of the bar at the one inn in Pelican Town, always drinking by herself. While I’m beginning to realise that life in Stardew Valley is all about cycles, Pam’s life is particularly predictable. Even in a place of repetition and routines, she is a special sort of constant.

She never wants to speak to me.

Pelican Town is incredibly twee. In the spring I arrive, it’s a village of picket fences, manicured gardens and swaying blooms of daisies or pansies or blue bonnets or whatnot. Its fat houses and shining pathways speak of comfort and calm, but I gradually come to discover that there are signs of profound sickness within. It’s not just that Pam lives in a trailer amongst all this, or sits alone at the bar every night, it’s that it all goes completely unacknowledged. On multiple occasions over the spring I alone try to engage with her, only for the game to give me the briefest, grimmest result.

“Pam is unresponsive. ”

--

I am twenty-one years old and I have been commissioned to write 250 Words for PC Format magazine. I’ve been published before, first at the age of eleven, but never offered money. My editor is very pleased with what I send in and, over the years, many, many more commissions follow, from multiple publications. Soon after, I tell one of my editors, PC Gamer’s Kieron Gillen, that “I can’t believe I’m being paid for this.”

“But you are,” he says. “Remember that.”

The message is that I’m a professional and people are trusting me to be practical and responsible in this job that I’ve wanted to do all my life. I forget to mention that I don’t really know what I’m doing, that I haven’t trained for this, that I don’t understand the industry standards or best practices, so sometimes my work suffers. When I’m offered large, multi-page or lead features, I feel there might have been a mistake. I really want to hold on to this opportunity, but I don’t know how, and all the people I work with are in a different town that seems so very far away.

A couple of times a month I send words and pictures to them via the internet, correspondence delivered from the land of limbo.

--

There is a boy in Stardew Valley called Alex. Alex spends most of his time trying to hide his frustration at the world beneath a veneer of confidence. He speaks in snarls, retorts and short self-aggrandizements that he thinks hide his unhappiness and he’s determined to be a professional sportsman. His determination manifests mostly as arrogant statements, I almost never see him train and I’m pretty sure he has no idea how to realise the dreams he has, nor how to dedicate himself. There is nothing in this village that will offer him direction or purpose or inspiration. He doesn’t even have anyone to play catch with.

One day he asks me if I think he might be a success one day. I don’t have the heart to tell him the truth and I don’t have the option to tell him what’s most important. Get out, I want to shout. Get out of this place. Get out of this limbo that will never offer you anything, because if you don’t it will kill you, piece by piece, and the first thing it will take will be your soul.

Still, I guess that in a village without opportunity or ambition, even a little skill means you’re the best. Alex can be the best here. Alone.

While Alex brags about town, I’m slowly, laboriously, turning seeds and soil into savings. I’m no longer falling on my face in the middle of the night and sometimes I work out my days well enough that I get to visit all the shops and services I need. Still, I spend most of my time alone, working from dawn to dusk, but I suppose I work best by myself. I know how to be self-sufficient, practical and responsible and I don’t know if there’s anyone here I can rely upon anyway.

I get a hint that two of the village’s most respected figures are having an affair. One of them tells me not to mention it. Nobody else says anything, so I suspect that either no-one knows or everyone knows. You can tell a lot by what people don’t say.

--

The only way I ever escape the black hole of my home town is by getting a student loan and going to a London university. It’s like a Faustian pact and to this day I’m still not sure when or how I have to pay my due. Or perhaps I already did, because outside of student accommodation, London is cruel. I am cold and penniless and confused by a city that somehow manages to be huge and busy, yet inconvenient and disorganised. I spend my days both studying and working, I spend my evenings counting pennies like a fucking cartoon character. I’m not ready for how much everything costs. Everything costs money, time and energy and I never have any of these.

I meet people whose parents are paying their course fees and rent. I do some sums in my head and work out how much that is per year. I multiply it by three, the length of a standard undergraduate degree in Britain. Some of these people have siblings at other universities, so I double or triple that figure. I wonder if those people have also done those sums in their heads, if they understand those figures, if that is normal for them. I feel naive for thinking that people like that didn’t really exist. After divorcing, it turned out neither of my parents had anything and my father went bankrupt.

I try to make time to read and write. I write a lot. It is bad. Sometimes I work or study way into the night. I make myself sick and almost collapse from exhaustion, unaware my body was so close to failing.

I get very sad. I work a lot and study a lot, forever meeting people who are more comfortable and more well-off. A lot of the time, I feel profoundly alienated. One day, someone laughs at my big old television set, because it is big and old and they think that’s hilarious. Another day, someone asks me why I don’t have a bigger travel budget than five pounds. Why don’t I just spend more money? Sometimes I shut myself away for days. One night, I drink an entire bottle of cheap scotch and pass out.

Paul is unresponsive.

--

I fuck up. Summer comes and it’s too hot for the spring crops that are still growing, so they just die. Money effectively evaporating into nothing. I go into the village to buy new seeds that suit the new season and Haley, a young woman who lives with her family, has no job and who scoffs at my work, criticises first my appearance and second my grass stains. She says my job sounds like a lot of work. Haley, I don’t have to stand on a concrete floor or carry forty kilo bags of cement or clean up piss. There’s worse.

I admit that I don’t know much about Haley, beyond that she is living in her parent’s enormous house while they are away travelling somewhere. I see no signs of any need for personal responsibility and I imagine someone who likes to use the phrase “Adulting” when she does laundry or cooks some food or pays a bill on time. She reminds me of an acquaintance who once thought it was absolutely remarkable, a real gas, that they were actually painting their own fence. Manual labour is hilarious.

I spend the next couple of days clearing and digging and planting and watering, for up to twelve hours, rarely going into Pelican Town except to dig a few semiprecious materials out the mine that I hope to use later. The real money, I discover, is not simply in growing things, it’s in making things. Oils. Wines. Jams. Cheese.

There is another young woman who I run into sometimes. She is almost always by herself, enjoying the outdoors, is keen to talk to me about botany or biology and works as a nurse. She is the daughter of Robin and Demetrius and her name is Maru. At the end of a long week of working in the hot sun, of trying to recoup my losses and make a wiser investment, I sit next to Maru and look up at the afternoon clouds. I leave as soon as she opens her mouth.

“Being a farmer must be pretty easy, huh?”

--

One day I completely run out of money. I have no money left in the entire world and am at the bottom of my overdraft, with months of unpaid bills and rent that my flatmate tells me not to worry about. I have been chasing the Student Loans Company for more than half a year to try to understand why they have not processed my loan and what I have done wrong. Eventually, they will admit there has been a huge clerical error and will send me the six thousand pounds that they calculate I should have received, but until then my family give me forty pounds and it feels like all the money in the world. I cry on the phone to my mother, because all I have been doing for years now is working and studying and working and studying and now I have nothing because somebody made a typo.

I meet a young woman in London who comes from somewhere a lot further away than a commuter town. One day she tells me a story about a time that her family didn’t have much money and what they had to do to get by. I find out why they left the black hole that was their home country. I hear stories about what was happening and why it was better for a child to grow up somewhere else.

I work more and study more and, very slowly, things get better. I finish my degree and I move in with this young woman and I love her very much. One night, I lie awake and I look at the single silver coin that is the moon and can’t understand how this has happened. It feels like a dream. Everything around me is the same silver colour and can’t possibly be real.

For a while I can’t get a job. She tells me it’s okay. She tells me it will work out in the end. I am terrified of being jobless and I am terrified of being a freeloader. The packed job center offers nothing and exists only as a mechanism to try and distribute welfare funds to London’s most unemployed borough. There is a riot on our street, outside our home, and people burn cars, buses, buildings. The riots spread across the country.

Eventually, I write. I am paid for it. My editor is very pleased with what I send in and, over the years, many, many more commissions follow, from multiple publications. I work constantly. I work my way out of a debt and a ruined credit rating. One day, I work twenty hours straight, sleep for four and then get up and carry on working. All it costs to climb out of that debt is time and energy. And my relationship.

Relationships end for all sorts of reasons. Like the truth, they’re complicated and complex things. But it will always help if you have one less reason to end a relationship.

--

One of Stardew Valley’s most reliable ways to make a little money is to comb the beaches every morning, selling off the clams and corals that wash ashore. There is a small cabin on the beach and inside it lives a man called Elliott. I step into Elliott’s home one day and very quickly realise it is a “sad boy house.”

Elliott is a “writer” and I have met people like him before. A cabin by the sea might potentially be an excellent writer’s retreat, except for the fact that Elliott seems to spend most of his time strolling around town or standing on a bridge and watching the river, waiting to be “inspired.” Elliott’s chief output seems to be occasional psuedo-profundities that one day made me think he’s probably a lot like a young Tommy Wiseau was. Having now made that association, my brain can’t unmake it and I now hear all of his lines in that voice.

Elliott is always talking about what he’s working on and I will never, ever read it. In all the conversations I have with him, when he tells me about how different and artistic he is, I never have the option to tell Elliott that writing is like farming, that it is slow and hard and if he made an effort every day, he would produce something in the end.

Elliott looks at the river and dreams and I think about a line from a Bruce Springsteen song about working people that asks if a dream is a lie if it doesn’t come true. I go back to work and Elliott goes on lying to himself about what he’s going to be every single day.

--

I sell or give away most of my things and use money I have made from writing to get on a plane and fly away to Vancouver, Canada. A river runs through it and it has beaches and mountains and forests that I can reach in mere hours. Animals wander in the wilderness and the seasons bring sun and snow. It is too melodramatically pretty to really exist. It feels like a dream and can’t possibly be real.

I live in a slightly shit apartment for a while, next to a weird neighbour, alongside skittering cockroaches, and I keep myself busy writing and filming, writing and filming, until things get better and I move somewhere nicer. I like a lot of the people here, but the people I like most are those that have worked hard for things. Every one of them has a quiver of interesting stories that they fire with the straightness and sharpness of honesty, a straightness and sharpness that makes any writer jealous.

--

Sometimes I open my Stardew Valley mailbox and there’s a gift from my video game mother in there, something small that she thinks might be helpful or useful. I don’t get to see my video game mother and I guess she’s very far away in whatever soulless town it was I abandoned. The gifts are things like cookies and they come with small, unobtrusive notes, the sort that mothers write when they don’t want to be getting under your feet. Every time I get a Stardew Valley gift from my video game mother, I think about my real world mother, who is very far away in a place that I abandoned and who sends me small, unobtrusive messages from the land of limbo. I think about her hopes for me.

Down by the river, also outside of the village, there lives a woman called Leah. Like me, Leah has given up her previous life and moved to Stardew Valley to be an artist. She paints and carves, working day after day trying to improve, and she spends a lot of her time alone. She’s humble about what she does and has nothing to prove to anyone, but I know what sort of things will happen if she spends day after day, week after week, practising her craft. She has a book on her bookshelf called “How to Deal with Overbearing People.” I want this book.

She puts on an art show in the village. People love her work. She also turns up at my house with a gift for me that she has made herself. It’s like Leah the video game character knew something about Paul the person.

I thank her and take the gift. I put it where everyone visiting will be able to see it. My dog sniffs at it and then runs headlong into a fence.

--

Post seems to take a very long time in Canada and a Christmas present arrives for me in the second week of January. It’s a small, unobtrusive box from my mother and it takes me a long time to slice through the tape and tear apart the cardboard. Inside are carefully wrapped little things that I have to pull so many layers of packing paper off, but I’m crying before I see them because I’ve already guessed what they are.

I tell everyone here who asks about my mother.

--

The first bottle of wine I make I give to Pam. I do this for no other reason than I can and it makes her happier. Sometimes we talk. She seems tired a lot, worn down by the world, but once the village’s broken-down bus is repaired, she not only has her job restored, she’s able to escape in a way that nobody else does.

Winter comes, the farm freezes and my breath comes out as clouds. I take care of some other tasks, go into the village and socialise a little more, though few people seem very different. It’s not just the farm that’s frozen, I realise, but the lives of Pelican Town. I start to think that what might seem like be paradise for some of the parents that moved there could be a perpetual purgatory for their children.

Leah and I wed in the new year, as the farm is coming back to life. At night, when the fire grows dim, she says she thought no-one would ever ask her to marry them. You’re telling me, I think.

She sets up a studio and works tirelessly at her art. To my surprise, I wake one morning to find she’s watered the entire farm. One day I will be able to afford everything I need to irrigate it, but in the meantime I work and I save and we get a barn and some animals. Sometimes my practical, diligent wife finds ways to help improve this ragged mess I have had the good fortune to inherit, like no boon I could ever expect in the real world. She never laughs at my big old television set and as the crops grow, as the cattle low and as the rain falls, we work every day and talk every evening of this sweet, blue bonnet spring. The seasons come, the flowers grow, and we build our farm as we build our lives.