The RPG Scrollbars: Saving World Quests

Words read: 2 / 1921

Previously in this column, somehow not taken up by the industry as of yet, I suggested that the word 'quest' was being somewhat damaged of late by the fact that it can be anything from 'Kill the Great Red Dragon' to 'bring me some orange juice.' I advocated a system where instead, tasks were split between two basic categories - what used to justifiably be called 'quests', and the more prosaic 'shit to do'. I realise now though that I missed an important third category, World Quests, named because scattering mostly pointless crap everywhere is much easier than actually filling an open world.

World quests come in many different forms, but typically 'icons on a map'. Kill this. Collect that. Blow up this. Keep doing it and typically your reward is something that would have been really useful about ten hours ago, but now only serves as bragging rights for the literally nobody interested in hearing anyone brag about their success in RPGs. The irony is that they're usually pretty easy to ignore, in terms of raw game, but always prominent as a way to level up a little more or get some extra cash that may or may not be useful later on, or simply obscure what you're actually supposed to be doing next. The biggest recent failing is of course Dragon Age: Inquisition's Hinterlands map, which many players found themselves playing to the point of screaming instead of playing as Bioware intended - to do some stuff, and come back later. "The Hinterlands" is now effectively industry short-hand for offering too much up-front, from regular quests to solving 'Astrariums', and closing wibbly green Rifts.

There's often a fairly wibbly line between world quests and simply optional side-quests. The easiest differentiation is that they're repeated content in some way, whether it's getting one of many things, or performing the same rite to shut a magical doorway, or defeating X waves of monsters to mark a location as 'safe', or exploring a ruin in search of a treasure that nobody in the game will ever send you after. Conversely, a FedEx quest to deliver something rarely counts, nor would tracking down a bounty hunter target or something like that. Usually they're shown on a map either up front or when you get close. Also, usually they inspire a sound not a million miles away from 'urrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrgh' after the first seventy times, usually with the general feel that being The Chosen One has become something of a janitorial position.

I don't really want to talk about the bad examples though, because they're both legion and speak for themselves. I think perhaps the nadir came in Assassin's Creed 2, not an RPG, I know, which somehow kept a straight-face while asking players put aside the quest for revenge and power in favour of collecting... feathers. Feathers. Fucking feathers. The Witcher 2's free DLC would subsequently parody this with its own tedious feather-hunting quest, and incredibly awkward finale.

What's interesting about the good examples of world quests is how easily they can be identified and built on by others. World of Warcraft for instance introduced them in the Legion expansion as end-game content, with each one a bite-sized chunk of regularly rotating content to try and cut down on the dullness of just running dailies, and a wide variety not only available, but available to choose from. Never want to do the 'find the lady' game played with barrels of beer? Just ignore it. Conversely, if you need the basic endgame equipment of Order Resources, Gold, key crafting supplies or equipment up to the current level cap, you can head over and get a pretty big payout. Mechanically, it serves to not only give players something to do, if only idly, but as a way of quickly catching up slower players and providing plenty of upgrade potential.

Nothing however does world quests as well as The Witcher 3, for the simple reason that like most of the game, CD Projekt Red based the systems around not just Geralt as a character, but Geralt's job as a monster hunter. You don't have to. In terms of cash, it doesn't pay well. However, it makes sense that you would, either while passing or at the bequest of some peasant, take a moment out of your day to stomp a monster nest or go after some creature not directly relevant to the narrative courtesy of a Witcher contract. It doesn't feel right to leave the situation undealt with, especially if you can do it on a ride through somewhere else. Likewise, retrieving the fancy Witcher gear from maps found in Scavenger Hunts offers funky new looks as well as the sense of completeness. Even if you never use them, at least by the end of Blood and Wine there's somewhere to stash the things instead of just treating them as more merchant-fodder. They're also wrapped in at least some story, of the fallen Witchers who once used them, albeit nothing crucial even if you're primarily playing for plot.

As with so much in RPGs, there's a lot more that could be done with world quests. Assisting different sides of a civil war affecting the overall result, for instance. However, not for the first time in the last month or so, it's Zelda: Breath of the Wild that really shows the rest of the industry how to design open worlds. It's hard to convey how well many of its systems work if you've yet to play it, but a good starting point is that though it does have Assassin's Creed style towers, they're purely used as observation points rather than a reason to cover the map in collectibles. Instead, the game itself gently guides you through the world and simply presents opportunities - an impossible climb for instance, which turns out to have a reward at the end of it. Bits of scenery that encourage you to throw things into stone rings and trigger characters to pop up without even thinking about it - feeling clever instead of just anally-retentive.

It even manages to make - and I can't believe it either - it manages to make collecting seeds interesting, just because the little critters hiding them are under every other rock or tree. Likewise, the game uses its raw mechanics to drive a lot of the game. It doesn't need to insist, for instance, on endless tutorials about cooking things up in the fire when it knows full well that you're looking for interesting recipes. The result is that exploring much of the landscape doesn't feel like a chore, because it's your own choice to do it, and there's still scope to be pleasantly surprised by what you find, instead of just working out how to get, to take a purely hypothetical example, a feather.

So, what makes for a good world quest?

The first part is that you can't just throw Something down and expect it to work, or for that matter just something that can be handwaved as 'a thing the hero would do', since that tends to be a very general platter of murderous and thieving activities. It has to feel like a diversion that's actually worth their time, even if the player knows that ultimately it's of tertiary importance. That can be, for instance, taking the time to build an interesting location, or having the player fight a tough enemy, or taking advantage of the fact that it being off the critical path means that the difficulty can be cranked up to present something familiar in a real gloves-off, come and have a go if you think you're hard enough, kind of way, with a suitable reward to match.

The second part is that the job should be, in itself, fun. Now, that sounds obvious, but I'd argue its a jump from the open-world games where this kind of thing started. Red Dead Redemption for instance had its treasure hunting challenges, where maps had to be found, deciphered and then solved. Assassin's Creed: Black Flag also had its treasure hunting, along with contracts. That mental element is the obvious thing to take. However, those games also put a lot of stock into making simple traversal into part of the game experience - riding through the desert or sailing a ship to a beautiful island, and then clambering all over the final destination and so on and having exciting encounters. Zelda too falls into this category. But even The Witcher treats travel primarily as a way of getting from A to B rather than something to do for fun, which radically cuts down on the excitement of wandering. Its world too is beautifully rendered - the game looks gorgeous - but it doesn't typically go in for points of particular scenic beauty to find and enjoy. (There are exceptions of course, like the palace in Blood and Wine, with its amazing vistas, or the painter quest, but they remain exceptions to the rule.) A monster's nest for instance is just going to be another bit of forest, not an incredible ancient temple to clamber over.

Third. The reward has to be real and imminent. That doesn't mean immediate. But part of the problem with most games is that they don't necessarily have much to give out for their side-quests that actually 'feels' notable - equipment can't be too good, or it unbalances the game, and it can't be crap, or it's not worth it. Gold is usually functionally worthless by the middle of every game. And if it takes too long to get some form of attaboy, then it's a pain. This is a challenge for every game to solve individually. Zelda for instance exchanges seeds for larger inventory space. The Witcher, as mentioned, offers unique looks and stories. Black Flag offers sea-shanties.

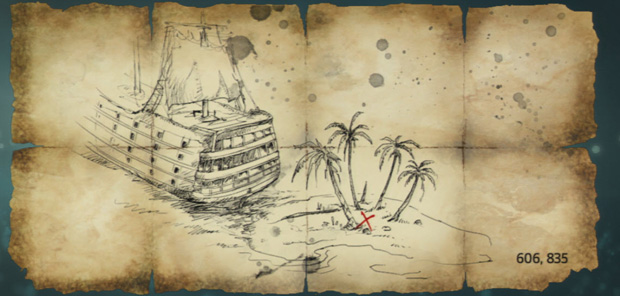

Incidentally, speaking of pirates, does this sound familiar to anyone else?

Just asking, because I'm suddenly sad we never got a piratical Ultima game...

Anyhoo, where was I?

Ah, yes. Fourth. If at all possible, the side-quests should have at least some bearing on the world as a whole. There's no reason for example that something like Fallout couldn't have you plant trees and have life return to the wasteland, or factor in the overall prosperity of a settlement into its end-game stats instead of just basing everything on big decisions. This one, I don't think is essential, but it's a good way of making all decisions feel at least a little meaningful.

Fifth. These quests really, really shouldn't slow anyone down. I am so looking at you here, Dragon Age: Inquisition, with plot quests attached to levels of Power well past the point that most players just want to find the villain, insert a boot into him, and catch the titles. The player that wants to scour the map and do everything is the player that will scour the map and do everything. Most just want to advance the story on at least a decent schedule, and know full well when everything's being blocked because someone in Marketing promised a 50 hour experience rather than 20.

And sixth, all these quests really need to start from the starting point that they're really not as necessary as many developers think. It's already hard enough for many players to find time to finish long games, be it because they have other draws on their time, or simply that owning a Steam account is to drown in enticing offers from a million different new experiences every five minutes. If the developers are excited by the side-objectives, as with the treasure hunts mentioned above, then awesome. If it comes down to simply filling the map with icons in some Ubisoftian push for perceived value then really, don't waste our time. None of that stuff ever, ever compensates if the main game isn't going to be good enough, and as the Hinterlands prove, more really can end up being less. There's always bits of the real game that better warrant the time.