Wot I Think: March to Glory

Contesting crazy paving in a cocked hat

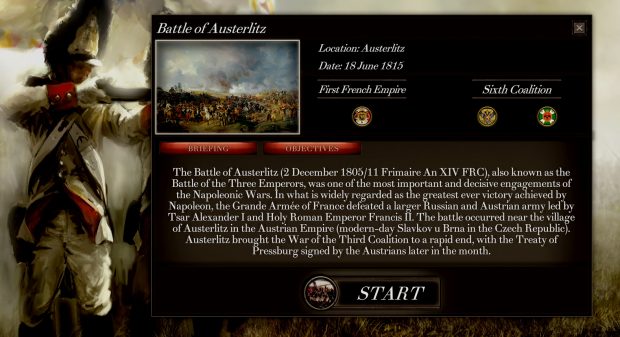

Shenandoah Studio are anti-hexites and proud of it. Equilateral, equiangular, six-sided polygons aren't common on their battlefields. They prefer more misshapen shapes – the squashed pentagon, the leaning lozenge, the skewed quadrilateral with one wiggly, dog-eared edge. The crazy paving makes for attractive maps but as I've discovered during my diverting but disappointingly smooth and brief March to Glory march to glory, creates problems too.

March to Glory is a far more conservative creature than Drive on Moscow, Shenandoah's finest PC release to date. The variable turn lengths, initiative system, weather changes, and 'prepared offensives' that ruffled DoM's IGOUGO rhythms and helped shield it from accusations of crudity, have no parallels in MtG. Come to this turnbased Napoleonic battle compendium expecting depth, fresh ideas, bold representations of things like command-and-control and fog-of-war, and you'll almost certainly leave crestfallen. Come to it expecting thoughtful minimalism, beginner-friendly tussles that won't weary your mouse hand or bludgeon your ego into a bloody pulp, and all should be well.

All fourteen of March to Glory's scraps have the following in common...

While deployment positions are, for no obvious reason, written in stone, before a battle commences you are permitted to buff a selection of units using a predetermined fund of 'Promotion Points'. Want that infantry unit in your centre to enjoy an advantage when fighting on hills? Fancy giving its neighbour an improved view range, enhanced reaction fire, or a little extra mobility? Just click the relevant icons and the blessing is bestowed. The cynic in me says this sort of player-reliant customisation is a lazy way to differentiate forces that really should have been differentiated by history-guided scenario designers or pithy commander representations, but given a choice between identical units and manually-modified ones, I'll plump for the latter every time.

Combatants come in three forms – infantry, cavalry, and artillery - the rock-paper-sabre relationship between which manages to be neither too stark nor too fuzzy. Although, naturally enough, foot soldiers do much of the deadly donkey work, cavalry (particularly adept at obliterating fleeing retreaters) and artillery (always vulnerable, but influential if well-sited) invariably earn their keep too.

Combined arms is often the name of the game. Keep your lone commander close to the fiercest fighting so he can rebuild shattered morale as quickly as possible. Force enemy infantry into squares with cavalry sallies then rake those squares with musket fire or cannon balls for extra damage. Push infantry or horseman forward now and again to turn 'unidentified enemy' icons into spotted units targetable by your big guns, or use them as rolling shutters - screens that part to allow batteries to fire, then close in readiness for the foe's portion of a turn.

A Panzer General-style results predictor lets you weigh-up the odds before ordering a charge or ranged attack. As, in certain circumstances, combat can do more damage to the initiator than the target, that advanced warning is invaluable.

Classified as grassland, forest, rough, swamp, hill, fort or town, map cells have a strict one-unit occupancy limit which can at times make reorganising a force a little like doing one of those sliding tile puzzles. At first I balked at both the non-negotiable “cavalry can't enter towns” and “units can't move from one enemy-adjacent cell to another enemy-adjacent cell” rules but I've come to appreciate their logic and plan accordingly. I do however remain uncomfortable with the automatic reinforcement system that allows units in towns and forts to painlessly replace casualties for turn after turn.

The map issues I alluded to in the introduction relate to terrain and line-of-sight. Naturalistic top-down visuals make spotting hill, swamp, and 'rough' cells difficult at times. Shenandoah appear to be aware of the issue because on some maps they've resorted to the rather clumsy expedient of labelling. The problem is the labelling is maddeningly inconsistent – sometimes significant terrain is tagged, sometimes it isn't. On the map above (where the red labels are mine) the ridge in the south-east has signage but bizarrely the protuberances north of it haven't. A toggleable terrain label filter would have helped but the Waterloo map features a far more elegant solution – hill cells sport predominantly curved edges, grassland ones predominantly straight ones. Heaven knows why this approach wasn't used throughout the game.

Being operational recreations, Drive on Moscow and Battle of the Bulge had no need for LoS/LoF rules. The more intimate March to Glory believes they are necessary and creates problems for itself as a result. In the two pics sandwiching this paragraph, optical common sense is conspicuous by its absence. The highlighted units (the units in the yellow areas) can't see potential targets because of obstructions in nearby cells. Crazy paving + crude LoS rules = occasional silliness.

Short of self-belief at the moment? Lacking in confidence? MtG could help. I've just completed the linear, fourteen-battle campaign (only playable from the French perspective) on the hardest difficulty setting without losing a single battle. Eat your cœur out, Monsieur Bonaparte!

Actually, don't. My uninterrupted string of triumphs owed more to generous victory conditions and a low-IQ AI than brilliant generalship. Having grumbled about the AI in one Slitherine Group title last week, I feel a little guilty about grumbling about the AI in another one today, but the skills exhibited by Shenandoah's Wellington, Kutuzov, Blücher etc leave me no option but to gripe.

MtG's artificial opponents - or, strictly speaking, opponent (it behaves similarly in all battles) – is easily overwhelmed once his various weaknesses have been identified. A fusser, he gives the illusion of dynamism by constantly shuffling units, but seems incapable of mounting a concerted attack or defending in anything other than a very static fashion. His nasty habit of pointlessly leaving units in vulnerable positions or throwing badly mauled ones back into the fray time and time again when healthier alternatives are nearby, positively invites defeat.

It's possible to progress through the campaign simply by causing more casualties than your opponent (victories through VL seizure are also possible). Once you learn that the sure-fire way to win the points battle is to pick your fights and pull back from unhelpful starting positions where necessary, it's massively tempting to do this in every scenario. If the enemy simply threw all its units in your direction simultaneously it might grind out the odd victory. Because it sits backs, preferring to pester rather than steamroller, and rely on the player's aggression to generate opportunities, it stands little chance even when given a helping hand by history or the scenario author.

Don't get me wrong. Constant analysis and a modicum of cunning is required to stay on top in some scraps. There were a couple of fairly tense moments in my nine-hour journey from Austerlitz to Waterloo, and in no engagement did I gain a sufficient points advantage to end proceedings prematurely (all clashes run for twenty turns unless all VLs are taken or the casualty ratio becomes excessively imbalanced). I guess, if I cared to, I could go back and replay, this time striving to fulfil the more demanding VL-linked victory conditions.

Shunners of the game's PBEM multiplayer who wish to continue battling after an initial playthrough have no option but to revisit the campaign. The “random map generator” mentioned on the Slitherine and Matrix Games pages, is actually nothing of the sort. It's simply a device that chooses at random one of the campaign clashes. It doesn't even have the decency to rearrange unit starting positions.

A pretty, weekend wonder that may never beat you but should never bore or baffle you either, March to Glory is a hard sell at £16. If you're in the market for some quality turnbased wargaming free of hexes and headaches, and don't already own them, I'd invest in Shenandoah's WW2 duo instead.

March to Glory is available now through Matrix Games and Slitherine, priced £16. A Steam release is imminent.

* * *