Wot I Think: YIIK: A Postmodern RPG

The Year 2000 Problem

YIIK: A Postmodern RPG ought to be a mixed experience. There are elements of the game, particularly the music, that are excellent. There are those, like the combat, that are not so good. I expected to be talking here about how I am a child who was born in 1994, and whether that affected my enjoyment of the game’s pervasive nostalgia bait, and other such interesting questions.

Unfortunately, it has a fundamental problem, and his name is Alex.

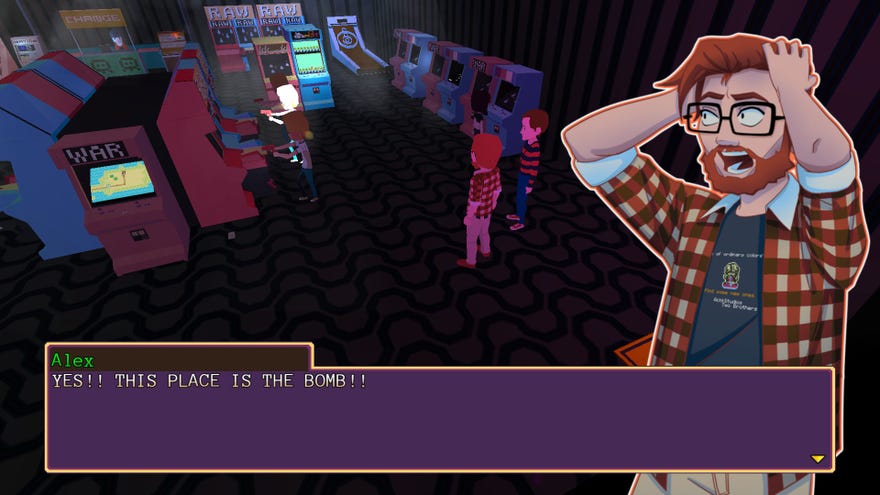

YIIK is a story-heavy RPG with turn-based combat and lightly puzzly dungeons. As the game progresses, you collect new party members who each have their own unique battle mechanics and find items to make them stronger. But it all begins with Alex following a cat into an abandoned building, where he witnesses a stranger (a woman named Sammy) get kidnapped by supernatural creatures. He decides to try to rescue her, which would set up a fairly standard (though somewhat tired) tale, if it wasn’t for the fact that Alex is so deeply unlikable that it is a major plot point.

It’s made evident enough from his everyday interactions, like the way that he complains about being asked to do minor tasks by his mother, who paid his way through college. In case those were too subtle, though, he eventually blows up and screams that he doesn’t care about the death of a 12-year-old girl, just to hammer the point home. Other characters call him out on it, but inexplicably remain his friend even though he continues to treat them like garbage.

Then, he is not given a redemption arc so much as an arc where he quite literally becomes the most important person in the universe and so all must be forgiven.

If that sounds convoluted, it’s because it is. And in conjunction with the wonky plot, the writing itself is stilted, too, especially when reflecting Alex’s inner thoughts. And, yes, it's often peppered with 90s references, Ready Player One style. Again, I was six in the year 2000, but even so they serve little purpose beyond jolting recognition in the player, and especially clash when given in-universe variations. Alex might talk about booting QuickTime on his computer, but he puts the ‘Backalley Boiz’ in his record player.

There are also hesitant attempts at social commentary. So hesitant that it’s difficult to tell where the game lands politically. Early in the game, Alex corrects his initial assumption that women can’t have facial hair, and then almost immediately makes what he calls a “lame joke” about “ginger” being a slur. The only black man in the group of friends, Claudio, leans on the fourth wall to point out that it would be a racist trope if he was the only one who could pick locks - and yet he is.

Claudio's sister, Chondra (the only black woman in the game) is given the most frequent and explicit lines about these kinds of issues, and yet they seem to go nowhere. She talks about her brother going missing and says no one cares when it’s black kids, but her brother is barely mentioned again and never becomes plot-relevant like the missing or dead white and Asian characters. She also pointedly asks Alex if he’s on a saviour mission as a white man chasing after a missing Asian woman that he barely knew, and while Alex is somewhat exonerated by the plot in spoilery and impossible-to-summarise ways, the actual game doesn’t seem self-aware enough to realise that it’s still trafficking in that same trope.

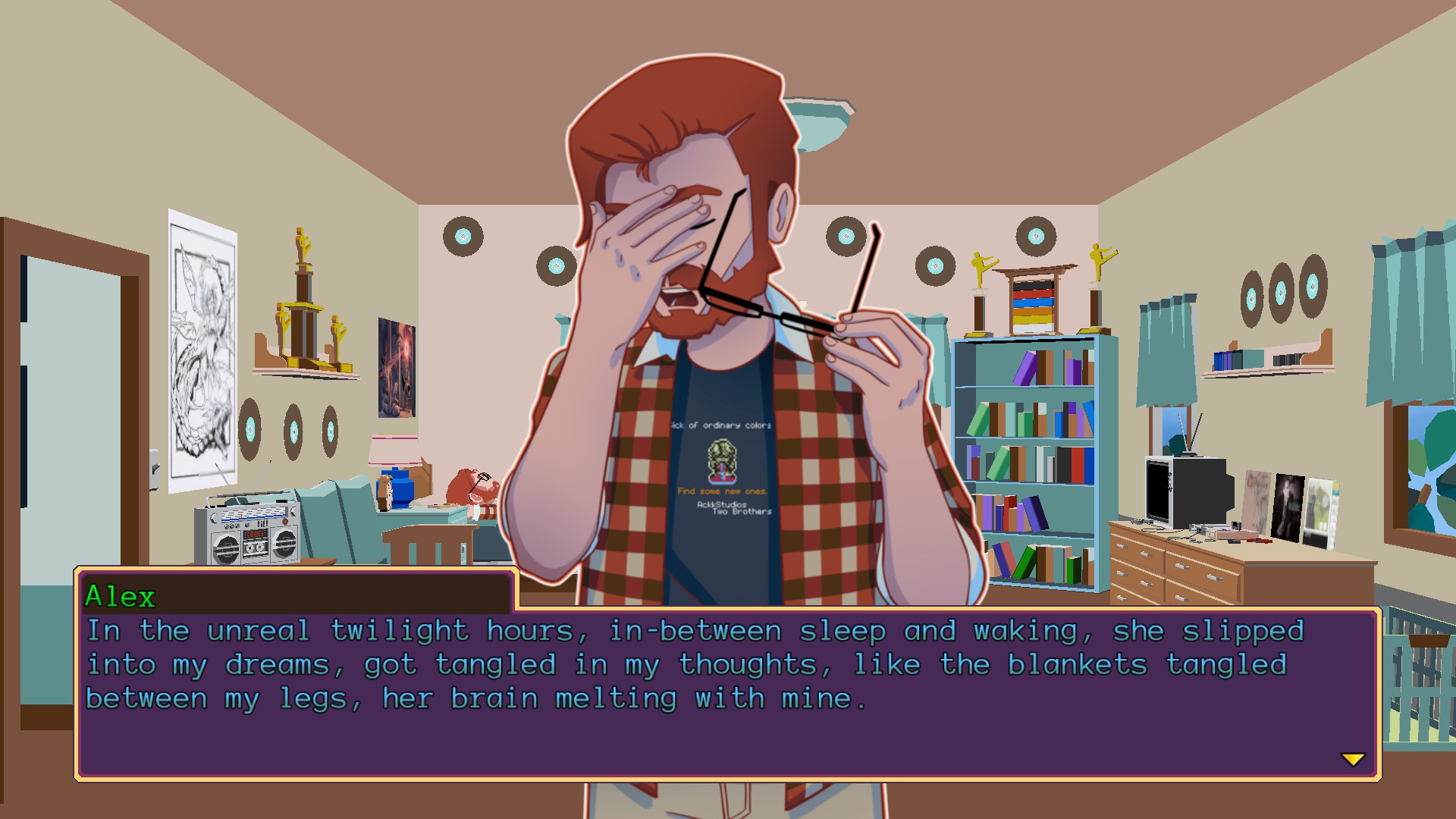

Chondra is also the only female character whom Alex is not madly in love with (apart from his mother, who makes two brief appearances to nag Alex about getting a job). After Sammy's disappearance, Alex meets and becomes obsessed with another woman named Vella, who knows far more than Alex but spends her whole time explaining things to him so that he can be the hero.

When her knowledge is exhausted, another woman steps into the exact same role. They might occasionally tell Alex that he’s being an asshole, but they never actually stand up to him, just accept his half-baked apologies and continue to have their lives revolve around his. Late in the game, the second woman tells him: “at every turn, I have been there for you, even when you have harmed me,” with absolutely no hint that maybe she deserves better (except me, silently screaming at my monitor after having put up with this for nearly 20 hours).

Those 20 hours are also made much longer than they need to be by the combat. Every character has their own style, in the form of rhythm or reflex-based mini-games, but they quickly become repetitive. Tapping repeatedly at the right time as Alex’s record spins to build up a combo, for example, gets old quickly, especially when most enemies have a tonne of health but pose little actual threat. Most of their attacks can be dodged entirely if you have the timing right, meaning fights become long stretches of chipping away at a too-long health bar and little else.

There is some solace in the fact that these long stretches give a showcase to the battle music, which is truly excellent. The music and sound direction are generally great throughout, but there is a special comfort to at least being able to chair dance along as you enter the thousandth consecutive identical fight.

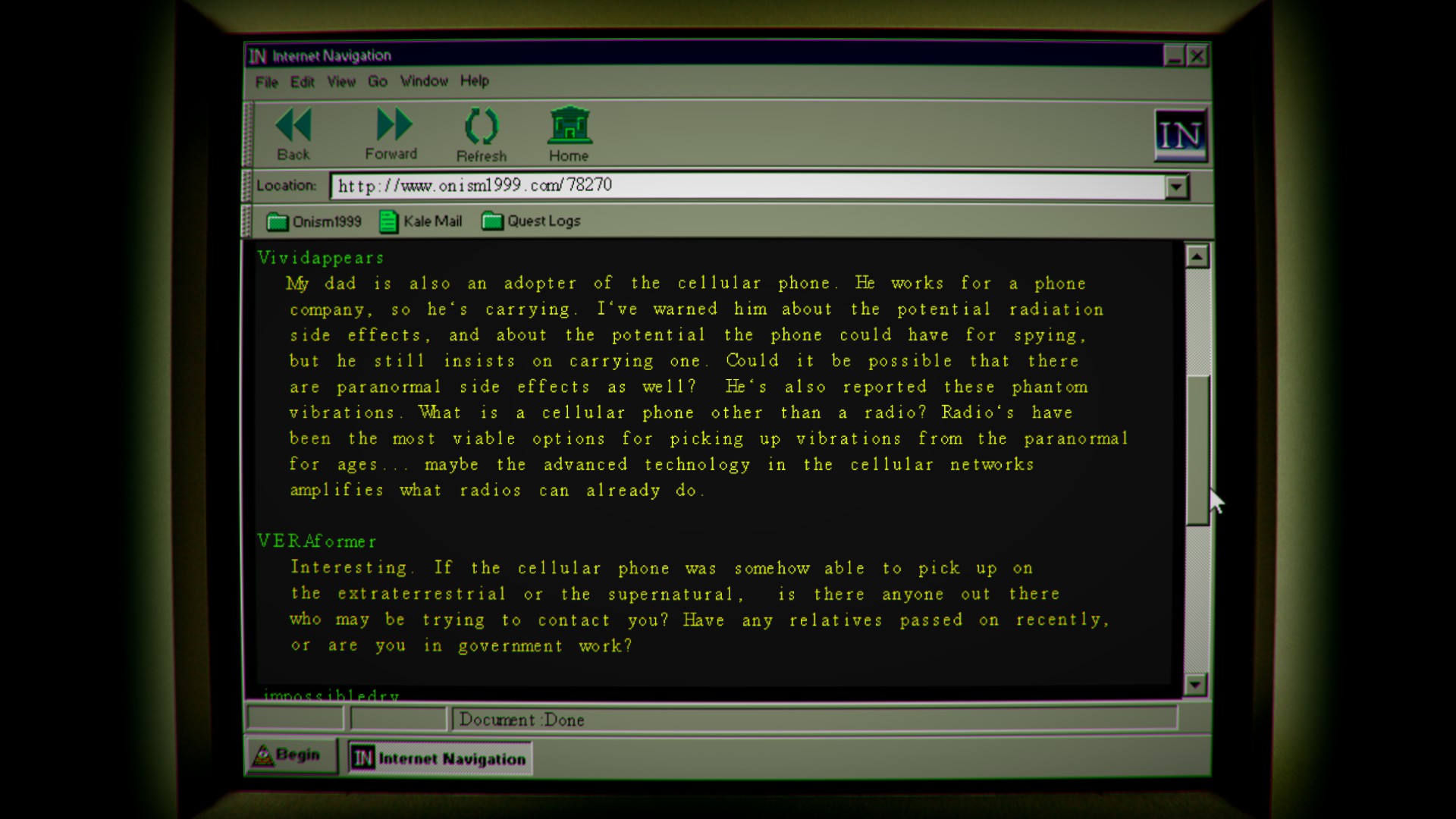

It’s small touches like these that make the overall frustrating nature of the game even more disappointing. The dungeon exploration is often a pleasant intermission, and there are some areas, especially in the late game, that are genuinely unsettling. A section that involves finding volunteers to be beheaded, and another where the phone just won’t stop ringing, creepy voices asking pointed questions on the other end, sometimes feel like they belong to a much better atmospheric horror game.

There’s also the PC interface, where you can access emails from other characters and browse a message board for fans of the supernatural. It is, perhaps, too realistic at times in portraying the awfulness of people online, but sets up side quests that can be welcome distractions. Reading a post about someone’s brother lost in the mountains above the town and then being able to go and find him and give him a walking stick so that he can get back safely brings the world to life in a way that the main plot simply fails to.

But then you’re in a dungeon and there isn’t a save point for an hour and the game crashes, so you have to repeat several battles and click again through a kindly exposition where one of the women coddles Alex far more than he deserves, and the whole thing comes crashing down.

YIIK might have been able to get away with some of its issues if other areas were able to pick up the slack. I’ve sat through plenty of tiresome combat to find out what happens in a story, and a convoluted plot can be fine if it’s allowed to breathe through interesting characters. But Alex himself is this game’s millennium bug, preventing the player from even rooting for their own actions, because they are all filtered through this deeply unlikable proxy.

After all, he’s the most important person in the universe.