The developer of retro RPG SKALD says he doesn't care if it makes money

Also has a nice jumper

While I’ve conducted a lot of interviews, I’ve never had one quite like this. The developer of SKALD: Against The Black Priory [official site] asks me to use a pseudonym and doesn’t tell me where he lives, but rather than being a shady character with a burner phone he is a comfortable dad with a lovely blue sweater. He leads me through a long discussion free of hyperbole, emphasising the importance of planning and project management, before concluding that he doesn’t really mind if his classic turn-based RPG game doesn’t make money.

But I don’t think our chat was humdrum, I think it was really good. As was the sweater.

SKALD is another one of those almost-solo-jobs, where developer “Al” has hired freelancers to help with the art and music, spinning every other plate himself. It’s a retro-style roleplaying game which “Looks and feels the way that we remember how games were played,” taking its most obvious influence from the venerable Ultima saga, but also nodding firmly toward the infamous Wasteland and the lesser known Magic Candle. It’s gone through the standard Kickstarter process, collecting 183,000 Norwegian Krone (about £15,500). Don’t get excited by that, says Al.

“It looks like a lot of money, but it’s not as much as you think,” he explains, his first example of “managing expectations.” He tells me much of the money is already accounted for in taxes, a Unity license, a new laptop and in paying those freelancers. “The quality of the art they make is really worth every single penny.”

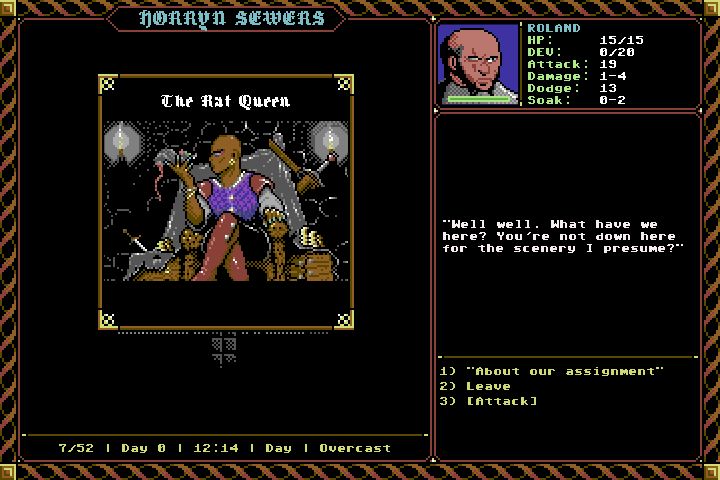

And then, somehow, we talk for half an hour about project scheduling, the importance of soft skills and even running local football teams. Forgive me if I skip over that for now. Instead, I’m going to tell you that I’ve tried an early build of SKALD and that it offers everything you’d expect, from turn-based combat with spells and swords to custom party creation and sixteen-colour dungeons. I wandered through a port, spoke to a merchant, squeezed into pixelated armour and stabbed my way through a spider-filled sewer.

It certainly reminded me of a particular generation of roleplaying games that I missed out on, their UIs accursedly clunky and their conventions maddeningly arcane. Al describes retro gaming as a “rose-tinted” subculture, and we forget inventory screens that were dreadful lists of text, or inane individual keyboard commands to (q)uaff a potion or (o)pen a door. Al’s created a mouse-driven, icon-based inventory, alongside context-sensitive controls that allow you to OPEN a chest or PET a cat (it hissed at me). He wants you to be able to save your game whenever you want. It’s important to keep that 80s feel, but revisiting the era is a reminder of both the limitations of the time and some very naive design decisions.

“One of the most interesting things you can talk about when you make a retro game is this almost archaeological examination of the genre,” Al explains. “Trying to see why things were the way they were, what’s worth bringing with you or what would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater. And you don’t want [your game] to be just a gimmick. You want it to be something that comments on the original genre. It should add some level of reflection, some improvement. It’s been really interesting for me to play old games and ask ‘Why did they do this?’ Was this a hardware restriction? Was this because they didn’t know better?'”

Not having to strain against hardware, Al is planning for SKALD to feature the complex dialogue and decision trees that we’re used to these days, as well as numerous side quests including a substantial civil war plot. While the look and feel will remain suitably retro, the cogs turning behind the scenes are shiny and new. SKALD will play more smoothly than any of the old Ultimas, and be a generally quicker game.

“I think the biggest difference between games back then and games now is designing to respect people’s time,” he says. “I think more people play games in short bursts. People will play games sitting on the bus. Or on the toilet.” I have no idea what he’s talking about.

“Games should be easy to pick up,” he continues. “You should be able to save when you feel like it. You should be able to progress through the story without grinding. And if you want to go through the game without exploring every nook and cranny... It doesn’t take away from the hardcore experience to have a critical path you can finish quickly.”

He’s considering a “narrative only” difficulty level for those who want to focus on the plot and, by keeping the game modest in scope, he avoids feature creep or the grandiose visions of more grandiloquent developers. He gets to respect his own time, too, and attributes this to his public sector project management skills, including “[having] to manage people, manage projects and manage money. Being professional. Being cordial. Not being an asshole online! That’s a tall order for some.” He’s clearly not a dramatic man and speaks more like a producer than a developer, which is rare amongst first-time indies. He sees SKALD as much as a project with a timescale as he does a game with content. It could be the first in a trilogy. It could be a failure. He’s very calm. His sweater is great.

“I don’t have to sell a lot of units to make money, but the money is what allows me to take a few weeks off work and rationalise to my family that I’ll be spending more time doing game development. And if it doesn’t pay off, no problem. It’s been an excellent ride.”

And this is where we circle back to what else is happening in Al’s life. He’s a family man with two children, somewhere in the “high north, a very, very rural part of Norway,” a town of only a few hundred. He doesn’t talk to his public sector colleagues about his secret life as a developer, saying they might be shocked if they found out. SKALD is the latest in a series of spare time projects “completely for my own enjoyment.” It just happens to be one headed for release.

“A large part of the time I spend doing this is time I’d spend programming anyway,” he says. “Playing computer games, or watching TV. In a sense, it’s still just a hobby... You could be a board member on a local football club. You could be anything. For me, it’s game development.”

Isn’t it unusual to be in your mid-thirties, making games but never putting them out there? “There’s a lot more developers out there like me than you would probably think. They want to make a game, because that’s the most enjoyable part. They don’t want the hassle of putting up a Steam page, setting up a Kickstarter, or fielding questions on social media. I really think there’s a lot more people out there with a game sitting on their computer that they keep polishing.”

Perhaps that’s my next quest: to find more of those games. And more of those sweaters.