A Panel Shaped Screen: the confusing world of multimedia franchises

Okay but did you buy the straight to DVD spin-off movie?

It was so much easier to just enjoy things back then. You know, then. The good old days. If you liked a game, you played it. If you wanted more, you looked for mods or became involved in the fandom. Once in a while, Hollywood would announce the movie adaptation of some popular game you liked, like Doom. Movies about games were always terrible, but you watched them anyway.

Then, stuff happened. Globalisation. Technological progress. Pop culture becoming synonymous with nerdy culture. The way we play games changed, and games themselves changed from single products to sprawling multimedia franchises. You can’t just like a game anymore. You like a franchise, and you consume it through a variety of mediums, like spin-off novels, comic adaptations and the inevitable Netflix animated series.

From a marketing standpoint, it’s a winning strategy. Making games is a hard, long and costly process. Releasing side-materials like comics allows developers to engage with the audience at a reduced cost, and to intrigue potential new fans who aren’t traditionally into games.

The reverse also applies. If tie-in games were once associated with poor quality, today they’re often better advertised and more polished, part of a coordinated effort to solidify a brand image through a variety of mediums. Think of the franchised Lego games, a series that manages to advertise several brands at once, while also getting glowing reviews. I am writing like a boring marketing person because multimedia franchises are, at their core, boring marketing stunts. That’s why I find them delightful: they come from a place of dull rationality, and yet they always manage to become a mess.

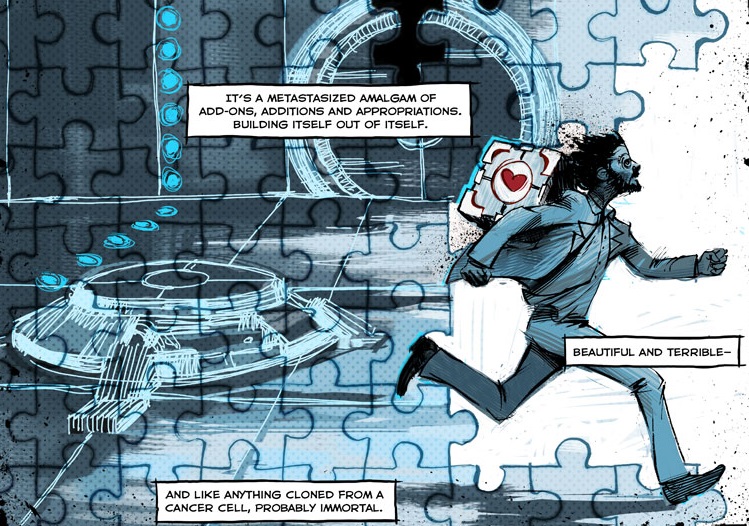

If chaos is a ladder, then multimedia franchises are the monsters living under the staircase. They are the many-headed rat kings running in all directions at once, a fistful of rodents held together by a knot of tails. Sometimes they manage to run somewhere productive, or do some clever trick. Other times they just devour each other.

Rat kings come in all shapes and sizes. The least dangerous are the least coordinated, composed by a main rat and some spin-off rats that are just… there. There’s a Dream Daddy comic, for example, but you probably haven't heard of it if you aren’t a devoted fan. It doesn’t add anything to the game’s plot: it’s a collection of self-contained stories about dads doing dad things together.

Dad hunting cryptids. Dad playing D&D. Dads having dinner together. You've probably read something on AO3 with the same plot. The same goes for the Terraria comic, or the one about Plants Vs. Zombies: they’re niche products, made for people already familiar with the source material. Official fan-fiction. Easy to read, easy to enjoy, easy to forget.

Other side-comics might be more closely tied to the main plot. They can cover what happened during a time skip, serve as prequels/sequels, or better explain the context for the game. Like the beautiful prequel comics Valve released prior to Portal 2, or all the strips that, over the years, fleshed out the world of Team Fortress 2. When used well, this kind of side material can enrich a game’s lore, while remaining completely optional. You can play Overwatch and hear Tracer quip about her girlfriend Emily, who only appeared in a side comic. It's a nice nod to those who did read it, but not being familiar with the extra stuff doesn’t hurt your enjoyment of the game.

Trouble can arise when a character gets introduced in a side story, and later becomes so popular they get added to the main game. Did you know Devil May Cry had an anime series? If so, you probably only learned it when charming broker J.D. Morrison got introduced in Devil May Cry 5: you wondered who he was, looked him up, and discovered he first appeared in an anime series you never watched. Also, in the anime he actually looked completely different. Are you confused? I am confused.

When the main game and the side stuff become too entangled, it can become a barrier of entry for new fans, now forced to read the side material to fully understand the story. When Disney decided to wipe away the whole Star Wars expanded universe, fans of the deep lore grieved. But the decision made sense! Disney wanted to introduce the franchise to a new audience, with a new trilogy of movies and new games. The confusing mess of spin-off novels, games, TV series and comics would have only intimidated new fans.

To avoid similar problems, sometimes studios keep their games and the side material firmly separated. The expanded universe is made an alternate one, a parallel dimension based on the original game, but with no clear link to the main series. A clean solution. Easy. The Sonic comics did that! Decades of stories about wars, galactic echidnas and new characters, all completely unrelated to the games.

Then a writer sued the comics publishers, claiming the intellectual property of all the original characters he created for the Sonic universe. The following lawsuit was so spectacularly chaotic that Sega decided to reboot the whole series, wiping away all contested characters in a snap of their fingers. Something about chaos emeralds rewriting the laws of the universe and deleting the memories of everyone involved? And you thought Marvel's Infinity Stones snap was a tragedy.

Multimedia franchises are creatures of chaos, sometimes difficult to follow or enjoy. And yet, other times their existence can be the only way to experience a long-lost story. You've probably heard about Fate Grand/Order, a mobile gacha game about scantily dressed historical figures on a quest for the Holy Grail. But FG/O is just the big cross-over episode of a decade-long series of games. Fate Stay/Night, the original visual novel that started the whole franchise, is bafflingly one of the few that never got an official English translation. So if you want to get into the series and understand what the hell is going on in FG/O, your only legal option it is to either watch the anime or read the manga adaptation.

Translations are a thorny topic here. Different mediums get licensed by different companies, and it’s easy to miss bits and pieces because the main game got an English translation, but the side stuff did not, or because different parts of the same story got translated in an inconsistent way.

Readers of the short story The Hexer probably did not realise the Hexer in question was actually Geralt of Rivia. Before the term 'Witcher' got popularised by the games, the original Polish word wiedźmin got translated into a variety of terms. In my country we called Geralt a strigo, an improvised male version of the word strega (witch in Italian). Other English translations used the term Spellmaker.

At their very best, multimedia franchises can be fun and full of surprises. At their worst they can become monstrous, tangling new fans in a writhing web of references, in-jokes, cameos and important lore stuff that only gets explained in that single light novel that never got translated in English, and which no one ever read — but if you go to internet archive, you can retrieve a Livejournal page from a Spanish student who knows a bit of Japanese and did his best to awkwardly summarise the novel in English...

...Or you could just enjoy the game and try to ignore the rest.

For the record, this week Giada sent the below image saved as 'header' and the top image saved as 'header you'll actually use.' Brava. - .ed