IF Only: What Will You, The Detective, Do Next?

>ACCUSE

The first piece of interactive fiction I ever played was Infocom's locked-room murder mystery Deadline. With a plot that turned on embezzlement and unfaithfulness, not to mention a fiendishly unforgiving set of scheduling puzzles, this is not the game I myself would recommend for a six-year-old. But I suppose my parents figured it wouldn't do me any harm, and it left me with a long-term affection for interactive mysteries.

The mystery is a natural fit for interactive fiction. The player has a clear goal. The focus of the story is usually firmly on past rather than present events. Locks, ciphers, and other standard puzzles feel at home in the genre. So many classic mysteries are essentially logic problems in fancy dress, so it's not a great stretch to do the same thing in game form. (In fact, here's Mattie Brice on why murder mystery writing can teach us about narrative game design in general.)

So if you have a taste for classic whodunnit genres rendered interactive, here are some highlights dating from 1995 to 2016.

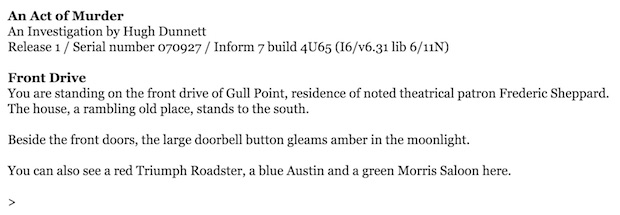

An Act of Murder (Christopher Huang as "Hugh Dunnett"). One of the consistently suggested ideas in IF is the mystery where the murderer and method are randomized at the beginning of play, so you can go through again and again. This is harder to do than it sounds, and most projects in this area never actually come to fruition. An Act of Murder is a notable exception, though: in a classic isolated-house mystery, the characters, means, and motives are reshuffled on each playthrough. It's possible to fail to assemble a good case on the first playthrough and let the murderer slip through; the replayability means that you can have a second try that is not simply a dull rehash of the first. Personally I found that about three plays was enough to get the hang of the system.

If you enjoy this piece, some of Huang's other pieces might also appeal to you: he's recently released Music, Mustard, and Murder, a short story's-worth of post-WWI logic solving suitable for Christie and Sayers fans.

Death off the Cuff (Simon Christiansen, Inform). You're famous French detective Antoine Saint Germain. You've gathered the suspects in one room (as you do) to announce the culprit. The only problem is that you have no idea who is actually guilty.

Death off the Cuff is a tight little one-room game in which you have to prod the various characters into giving themselves away, so that you can swoop in and announce your deduction. It is, of course, partly a joke at the expense of unrealistic Poirot scenarios, but it makes its point interactively, a quick-playing good time.

Victorian Detective (Peter Carlson, Quest) is the first in a series of Sherlock Holmes-style mysteries in which you check out crime scenes, then say what conclusion you've reached. The production values are pretty rough-and-ready: the text often backtracks and reprints a description or partial scene you've already encountered. There are illustrations, but they're hand-drawn and not particularly well-scanned. The prose doesn't read like Doyle.

And yet the series has a following, and it's not too hard to see why. The narrator is endowed with implausibly strong observational skills — at one point in Victorian Detective, you identify the cat breeds of some cats who left hairs on a man you had run past the night before. Each step of the mystery poses its own tiny puzzle of logic, inviting the player to put together evidence from examining different items.

At the same time, the choice-based setup provides enough structure that the player has a reasonable chance of reaching the deduction the game is looking for. In contrast with a Phoenix Wright game, the player is only expected to deal with a small amount of evidence at a time, so your odds of finding the right option are pretty good; but the story keeps moving forward even if you fail. There's no option to lawnmower through your evidence inventory here.

Where Death off the Cuff is making fun of Poirot, Victorian Detective is straightforwardly glorying in the tropiest possible Holmes. If you like it, Victorian Detective 2, Victorian Detective 3, and Victorian Detective Interlude also await your deductive skills.

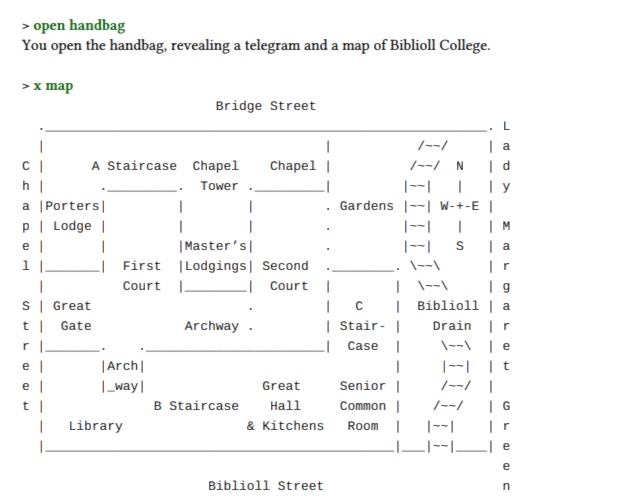

If your taste runs to longer pieces, you're in luck. In Christminster (Gareth Rees, Inform), the heroine, Christabel, is searching an Oxbridge college for some indication of what happened to her brother. Women aren't yet allowed in men's colleges, and she has to negotiate both social and and physical obstacles to get anywhere.

Christminster comes from the early days of hobbyist text adventures — 1995 — and some of its design decisions are definitely of its age. Unfortunately, one of these is the first puzzle, which makes it unnecessarily difficult to get started; a glance at a walkthrough may be necessary here. But once you're past that point, the game has a lot to offer, with a wide range of research and exploration puzzles; a well-observed setting that changes over the course of the day; and a number of set-piece scenes with deliciously obnoxious villains. It's justly considered a classic.

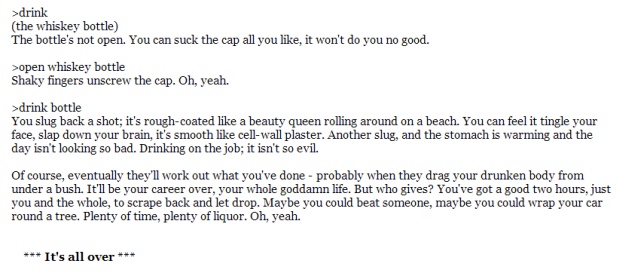

And if you'd prefer noir? Make It Good (Jon Ingold, Inform) is a terrifyingly ingenious piece of parser interactive fiction with a huge cast of active non-player characters. Not only do you have to figure out what really happened, you also need to manipulate the other characters into doing what you want them to do. And unlike NPCs in many other text adventures, these NPCs have their eye on you. They will notice if you try to sneak past with a bloody knife. They will draw their own conclusions if you ask the wrong questions about the wrong things. Soon you'll find yourself creeping around the house with pieces of evidence coyly tucked into a closed container so that no one will notice what you're up to.

I had to play through a number of times in order to win — this is not an easy piece, and you'll need to develop a rather machiavellian game plan in order to bring the whole situation to a satisfactory conclusion. But it is also one of a handful of games that genuinely relies on the player developing a sense of the characters' psychology and manipulating that. There are plenty of clues to discover in Make it Good, but they are gated by your ability to explore and to manipulate the story, not by random combination locks and arbitrarily placed blockages. If you've ever been curious about what a text adventure could do with a really well-populated world, check out Make it Good. (Here's Graham's take on the game as well, closer to when it came out.)

[Disclosures: Emily Short has eaten sushi with Chris Huang and stayed over at Gareth Rees' house. She has done business with Jon Ingold's studio inkle. More generally, Emily is not a journalist by trade and works professionally with various interactive fiction publishers. You can find out more about her commercial affiliations at her website.]