Blue Prince is already the very best shapeshifting videogame house

Cellar door

I'm currently trying to find a new flat in London. This is not much fun, though it's a great opportunity to meet and bond with other would-be tenants over a shared, grinding resentment of landlords who will literally stuff a bed in a toilet and call it a "studio apartment". It's also left me powerfully invested in the premise of Blue Prince, a first-person puzzler which looks like a graphic novel and starts with your character inheriting a huge, weird, isolated mansion, Mt. Holly, from an eccentric great-uncle.

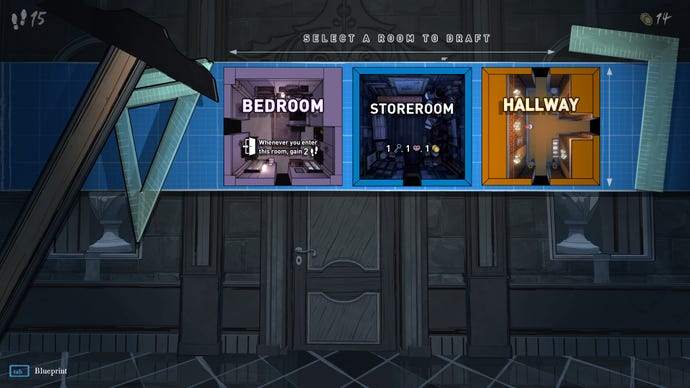

Lucky you! There's a catch, though: according to your great-uncle's will, you only get to keep the place if you can find its 46th room. The catch hanging off that catch is that going by its flatplan, the mansion only has 45 rooms. And the catch hanging off that catch is that the mansion changes shape between visits. Every time you open one of its many doors, you must choose from three cards to decide which room is on the other side. To find the elusive 46th room, you must "draft" rooms in certain combinations to unfold the mystery of the place and wiggle your way to its heart.

Tonda Ros, co-founder of California-based Dogubomb, has been making Blue Prince for almost a decade, working by himself for a couple of years before gathering a small team to flesh out his prototypes and overhaul the initial, stock-asset art direction. "I come from a filmmaking background, so I wanted to make a really atmospheric, narrative-heavy first person adventure game initially, when I started in around 2016," he tells me. Inspired by celebrity indies such as Braid and Limbo, Ros experimented with coding his own house environment, while also tinkering around with some ideas for table-top games - his inspirations there include Agricola and Labyrinth.

"I had a design of drafting rooms where you passed room cards from player to player, and you're each selecting one room to draft," he goes on. "So I was like, 'Okay, I wonder how that would combine with the first person adventure thing?'. And so I built a prototype in the first three months. And it was really fun. And I was like, 'Okay, maybe I'll commit to another six months and finish it'. That was eight years ago. So my timeline was a little off. And the ambitions grew and grew. And I think the more I went on, the more I became obsessed with the idea of everyone's day [in the house] being different."

Blue Prince's unearthly house is laid out like a chessboard on your drafting menu, with nine ranks pointing northwards from the lobby towards the other exit. Moving between these rooms costs steps, of which you have a limited quantity per in-game day. There are three other main resources: keys for unlocking doors and other objects within rooms, coins, which can be spent in various ways, and gems, which are needed to draft rarer varieties of room.

These four, reassuringly tangible commodities sit atop and feed into a Byzantine boardgame economy of room states and effects. Some rooms work like terrain hazards, stealing a coin when you walk through them, while still potentially being necessary to make progress. Others, such as bedrooms, refresh your character's wits and restore a few steps, every time you enter. Better, then, to draft a bedroom in the middle of the house layout, so that you pass through it frequently. Or, if you're focussed on exploring and learning during the run in question, draft several bedrooms to keep your stamina topped up, instead of rooms that might be more relevant to the overarching puzzle.

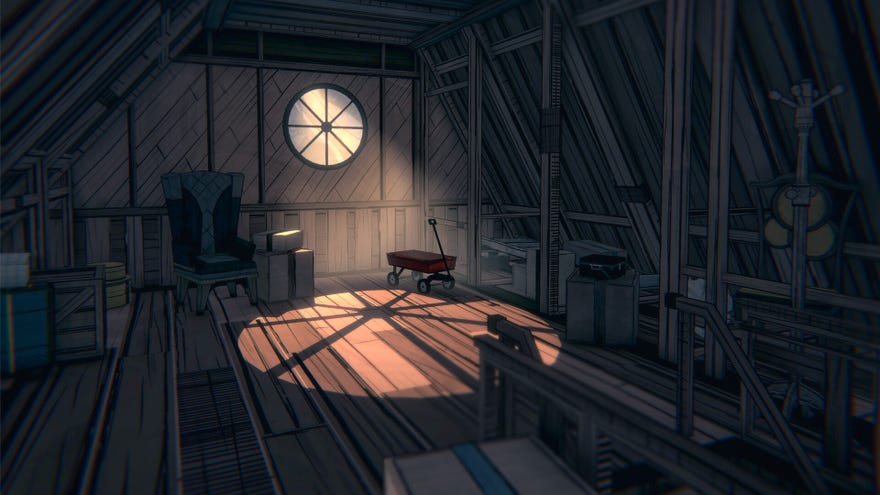

Some rooms have effects that multiply when you draft several of that type at once. Others evolve individually when you play them again and again. Draft an observatory repeatedly, and you can look through its telescope to discover a new constellation each time, with varying consequences elsewhere in the house. There's a grand dining room where a hearty meal is served by unseen agents at a certain point every day, as signalled by a bell that never failed to make my skin crawl, during my 45 minutes with the game. Blue Prince isn’t horror in the sense of jumpscares and gore graffiti – indeed, many of the rooms are very cosy (certainly by comparison to the average “delightful”, “fully furnished” “maisonette” on London Zoopla). But the house gradually envelops you in a way that is all the worse for you being its architect. It’s… troubling to look back after drafting a few rooms in a straight line and join them all up with your gaze. It feels like feeding your whole arm into a big, silent machine, fumbling around for a single cog that isn’t marked anywhere on the blueprints.

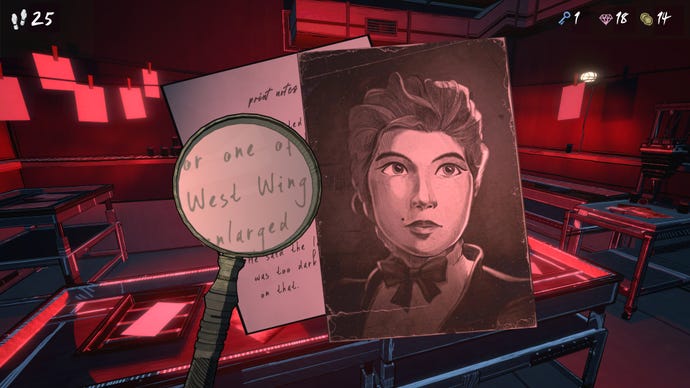

You'll find tools, as well, like a magnifying glass that lets you read tiny clues in any books or pictures you discover. There are keycards for electric doors. Some rooms contain circuit boxes that rout power between those electric doors and other gadgets. There's a darkroom with pegged-up photographs, which can't be seen until you turn on the lights. And then there are the rooms and artefacts that crack open windows upon your great-uncle's past, and hint at an explanation for the mansion's bizarre behaviour.

"The whole game is kind of designed in a very modular, nonlinear way," Ros says. "So if you haven't figured something out, that's OK - I've designed every challenge to be attacked from multiple angles. And for you to be able to solve things by thinking outside of the box, so there are often-times multiple solutions to puzzles."

He's found it exhilarating, watching different players discover different combinations of rooms and apply different strategies to the deck. "We've done three years of internal playtesting, and the cool thing is that I've seen so many styles of play. And we've designed the game to embrace everyone's style. There's people spend two hours on each [in-game] day. And there's some people for whom every day is 10 minutes. I'd say the average day is about 30 minutes, for the average player, but it depends on how good at strategy you are. As you solve puzzles in the game, you unlock permanent upgrades, that may grant you more resources each day, so that it becomes easier, the more puzzles you solve. But for players that don't really like puzzles, they can just play it as a more difficult strategy game."

I had absolutely no idea what Blue Prince was before setting foot within it, and now, I can't stop thinking about the game. There's no urgency to it - time stands still providing you do, and I've seen nothing so far in the way of elements that require quick reactions or dexterity, let alone any explicit threats. Still, it's an immensely creepy creation, for all its calm. Whatever the order in which you lay out the rooms, you are always building a labyrinth with some kind of minotaur at its core. Coins, stars, gems and steps aside, the most important resource at your disposal is, of course, information - information, and a generous pinch of luck. "I think it's possible, technically, to beat the game in a single day," Ros says. "But everything has to go right, and you have to be incredibly bright."

Blue Prince doesn't have a release date yet, but you can wishlist it on Steam.