CryEngine & The British Library: 2013's Unusual Team Up

EA and the NHS

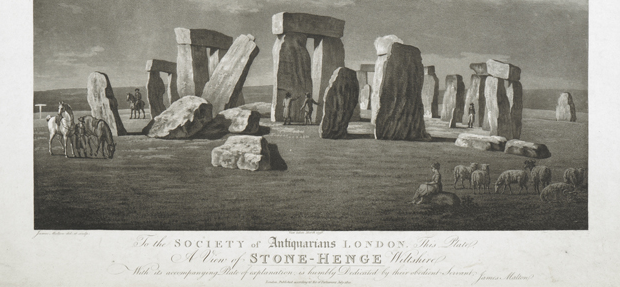

It's October 2013 and I'm sitting in a large auditorium at the UK's best games festival, GameCity, awaiting the reveal of the Off The Map competition. Student developers were given access to three different historic maps from The British Library as their inspiration: The Pyramids of Giza, Wiltshire’s Stonehenge, or London around the time of the Great Fire in 1666, allowing them to interpret the information into CryEngine scenery and architecture.

They've been working on their interpretations since January with support from the experienced Crytek team. I'm not sure what to think at this moment: earlier in the year I'd attended a GameCity Nights event where a Crytek employee found out I was that woman who was mean about Crysis 3, and there was slight awkwardness in the moment just before he hugged me really quite warmly. But as the teams' 3D interpretations of their chosen British Library maps and illustrations are projected onto the stage in front, I begin to see something being connected up. They'd created a place where history and games could do more than just gouge each other for content or rudimentary education, but could become symbiotic places to preserve, excavate, explore.

It's no mere Time Team reconstruction, this Off The Map stuff, I say to myself as I sit there, stunned at the images. The CryEngine can do things other than render futuristic killmen. Off The Map's three most potent ingredients, CryEngine technology, beautiful old British Library documents, and the talent of the participating teams are what made it one of my favourite collaborations of this year.

Often the GameCity festival focuses not on what games are doing, but what they aren't doing. It provides a space for innovative, interesting, experimental things to be done by talented designers, artists and other diverse creators. Previously, GameCity has hosted collaborations between EA and the NHS, or Eric Chahi and a chef. The British Library and Crytek provided GameCity with the opportunity to do something different with a design competition.

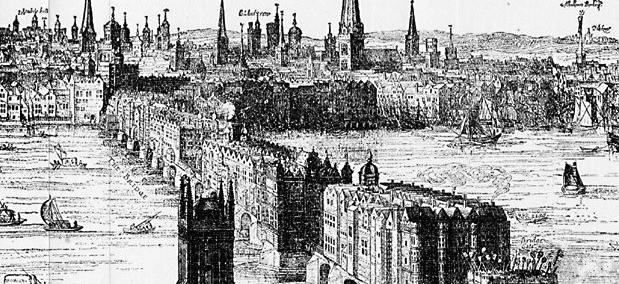

One of the illustrations supplied by the British Library: Stonehenge.

"For us it was about establishing a new platform in the festival to play around with and build on, to start new conversations about videogames with," Iain Simons, the GameCity festival director explained. "Like most of the bits of the show, it’s about trying to make the best possible conditions for brilliant people to be brilliant in - so we were really hoping to be surprised by the entries, and we were. The best outcomes for me, were the different kinds of conversations it started. The British Library brings along a certain kind of discussion, obviously Crytek does the same, and the net result is a lot of different people having different kinds of discussions about video games and what they can do in the world."

Tom Harper, Curator of Antiquarian Mapping at the British Library, gave a talk before he presented the award to the winning team on the project. In it, he emphasised that the modern differentiation between maps and art is a recent distinction. Speaking via email, he told me: "The difference is simply a question of degrees and until the late 18th century it didn't exist at all. Military surveyors were as capable of producing a pretty picture as a large scale military map. The opportunity for immersion in an artificial landscape is incredible. The distinction between the two suddenly disappears with the videogame view or simulation. I personally believe that simulations are maps as much as views are, and I don't think you'd find much disagreement generally about that. Even when you introduce a story or narrative there isn't a problem, since maps contain stories too. They are just static."

Tom gave the example of Scenes from the Passion of Christ by mid 15th century painter Hans Memling (above) as an example of a virtual world that the eye could travel through to create narrative, one that existed well before video games started plotting out their fanciful art. "Firstly, it is another virtual landscape (a map!), secondly, it has a narrative embedded in the landscape - that of Christ's passion and death. Moving your eye from one scene to another, surely you are creating the idea of movement? I know this is obvious, so apologies. But I guess what I am saying is that the relationship between types of representations is very very strong and instead of trying to distinguish, we'd be far better doing the opposite."

But Tom is not ignorant of the power of games to create imagery just as powerful as some of the antiquarian maps he curates. Speaking at GameCity he told us: "SimCity will go down as one of the great 'maps' of the 20th century - in fact I say so in my book, '100 maps of the Twentieth Century', to be published Autumn 2014.

"It is of its time, absolutely, undeniably and brilliantly. And it has fashioned the world view - through maps, 3d perspective views, information expressed geographically - of a whole generation of European and North Americans. The video game environment may have reflected much of their makers but subjectiveness is to be expected with the creation of any virtual world. ...The player begins with a blank canvas: some grassy ground, some trees and a river on which to develop a city from scratch. Now, one might suppose from the idea of creating a city from scratch, the grid pattern development, or even the idea of undeveloped land as somehow a blank canvas, that the maker of the game was American in origin."

But what of the outcomes of this amazing project? How did the teams fare? Runners up to the competition Team Faeriefire, five students from Newport University, interpreted Stonehenge as an ethereal, dreamlike place in Cryengine, as evidenced by their bright, bold artwork.

Runner up team Asset Monkeys also took Stonehenge as inspiration, but burrowed deep below it to create eerie catacombs.

But the winners of the competition, six students studying Game Art Design from De Montfort University who formed Pudding Lane Productions, looked very closely at the maps of London around the time of the Great Fire. Working from Claes Janszoon Visscher's London, 1616 and Wenceslaus Hollar's London, 1666, they did a very detailed breakdown of how they imagined the streets and buildings of the city to look and feel. A section from Claes Janszoon Visscher's London is below.

It was an unexpected joy to be rendered silent by what the team had produced.

"They used [the given maps] as a way into the period and the place," Tom Harper said. "They got a feel for it. They then went out exploring primary and secondary sources to detail their virtual maps."

In fact Pudding Lane Productions did much more research than just looking at the maps: they went to visit The Shambles in York to get a real sense of 17th century architecture. "We got a real sense of just how tightly packed the streets of 17th Century London would have been," team member Joe Dempsey wrote in March. "At some points on The Shambles street you could literally outstretch your arms and touch the buildings on opposite sides of the street, the tops of buildings were actually inches from touching."

From Pudding Lane's development blogs, some interesting problems arose. One was that houses from the period were not all of a regular shape and size, and many streets were winding and irregular, and so modular buildings had to be made. Another problem that the team encountered towards the end of their project was that a lot of streets began to look the same, and so team member Chelsea Lindsay began making props for the map. Joe explained on their blog in April, "Whilst it has been my job throughout the project to plan and produce concepts for Pudding Lane I was happy to take on the important job of designing and building the model for Farriner's (or Faynor) bakery which is located on Pudding Lane. The bakery bears some significance to our project for a number of reasons, first of all our teams name 'Pudding Lane Productions' and the fact that our level has expanded outwards from Pudding Lane. As well as this Thomas Farriner was actually the Kings appointed baker, but most importantly Thomas Farriner's bakery on Pudding Lane is the location in which the Great Fire of London is said to [have] started."

The extraordinary amount of research undertaken for the project is obvious from the blog: even tavern signs were taken from documented evidence of the period.

I asked Tom Harper if the abilities of the developers and CryEngine had impressed him. "Amazed," he said. "I'm certainly not a gamer - though I have tried Proteus! - so I was really impressed with how illusionistic and immersive the experience can be. Yes there's a screen, just like there is a piece of paper. But the degree to which the technology was able to break that barrier was really subtle. The Cryengine is clearly a very powerful tool. I think Pudding Lane were pretty good as well. I know Scott from Crytek was pretty blown away by their skill. Where does their skill stop and the beauty of the Cryengine start?"

Is this use of sophisticated technology to recreate historical locations becoming more commonplace? "Certainly the heritage sector are using it," Tom said, "though in a moderately superficial way. Certainly one can make extraordinary connections by placing things together and animating, in order to compare them. Our Georeferencer project - where old and new maps are matched up and overlaid, does that to an extent. We have an incredible amount of documentary evidence - photos, maps, views - of our urban spaces over 500 years - in the British Library. Getting this material into digital form, so that it can be used, recreated, animated in ways similar to Pudding Lane, is one of our major goals."

The GameCity competition will return in January. Meanwhile, you can gaze at the entrancing details of Pudding Lane's work here. Someone employ them. They were my favourite developers of 2013.