Premature Evaluation: Cryptark

Skeletal Horse-Robots From Spaaace

Each week Marsh Davies attempts to retrieve some sort of thematically appropriate salvage metaphor from the Early Access game he’s been playing - which is perhaps too easy when the theme of that game IS salvage. But Cryptark is no stricken husk: it’s already proving to be a truly excellent roguelike shmup. In it, you’re dispatched to disable the security systems of derelict alien space-hulks so that they can be stripped for scrap, one after the other, until you locate the eponymous prize itself, a gigantic vessel chock-full of precious alien tech.

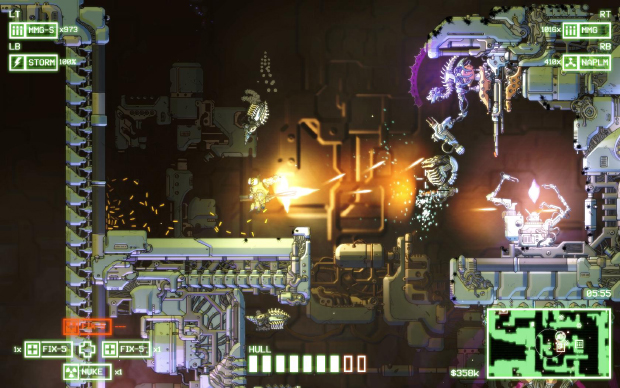

Derelict is apparently a relative term, however. The hulks are still occupied by swarms of drones, seemingly constructed out of metal and horse skeletons, which will viciously punish your trespass. Still happily throbbing, too, is the ship’s giant pink brain, which is your mission’s goal: destroy that and all the ship’s other systems will shut down, leaving it vulnerable to your fellow salvagers.

So far, so shmup - but Cryptark makes this strategically interesting by protecting the core with a number of other interrelated systems that you can choose to take down first. The core may have a shield for instance, or an alarm system that will alert all the ship’s drones to your position. And these drones may be endlessly resupplied by a drone factory which can build and teleport them to your location. And any of these - the core, the shield generator, alarm system or drone factory - might be secured by the door locking system, which, once disabled, might be then quickly repaired by the ship’s repair system unless you choose to destroy that first.

Brilliantly, each of these systems is a mini-boss in itself, with bespoke tactics required for its destruction. The shield generator is encased by what might be rotating radioactive broccoli, which deflect incoming fire right back at you, forcing you to perform synchronised strafing runs, or spend valuable time waiting for openings before unleashing volleys of fire - all while fending off the attacks of drones. The repair system will, unsurprisingly, repair itself while distracting you with a buzzing cloud of bots. They’re easily destroyed, but while your attention is turned, the system’s health pool has all but replenished. The door locking system requires you to key in a series of increasingly complicated D-pad instructions. The gimmicks of each are perfectly gauged to be challenging under time pressure, but trivial enough that their repeated encounter on each new ship is not a chore.

And so you plot a winding route through the procedurally generated ship’s interior, balancing the threat of each system against your dwindling ammunition, your gun-suit’s hull integrity, the potential for resupply while on the mission and the ticking clock. Each hulk needs to be disabled in a meagre handful of minutes, after which your reward quickly reduces. This is extremely significant, not to the success of the mission you’re on, but to your campaign as a whole. Your intent is to reach the Cryptark itself, but the game’s central contrivance is that the information of its whereabouts can only be found by salvaging other ships in the dead alien flotilla first, each successful mission advancing you through one of the six tiers of difficulty until you reach your target. Salvaging these early ships, however, only just covers costs. You have a starting budget of 500k for the entire campaign, and, even in the early stages, a failed salvage operation will easily dock 100k from that total. And so the campaign level strategy influences not just the mission level strategy, by forcing you to ignore dangerous systems in the hope of a quickly lucrative smash-and-grab, but also your moment-to-moment tactics, as you scrimp on the weapons at your disposal.

The developer’s previous game, the Greek-themed side-scrolling combat adventure Apotheon, relied heavily on a procedural animation and physics system which occasionally made your character feel like an ineptly rigged puppet. There are no such problems here: Cryptark’s combat abilities have been as well considered as the layers of strategy that inform it. Gunfire is abrupt and kinetic, some weapons sending both your enemy and yourself skittering back through the vacuum as you fire.

Avoiding gunfire proves just as fun. The enemies you are pitted against come in many forms, each with their own attack patterns and weaknesses - the tactics required to neutralise them shifting in exciting ways as your armoury develops. Enemies with powerful frontal shields must be effectively strafed, the nose-dive attacks of other drones timed and avoided. Laser sights track you before unleashing devastating missiles, while other enemies deploy energy vortices that explode after a time. Juggling your dash move and your ram attack can get you out of the line of fire at critical moments, allowing you to pop a few grenades over the shields of a heavily defended core system, before zipping back out of the killzone, kiting a swarm of enemies into a narrow corridor where they can be easily dispatched.

There are many, many different weapons and tools to be fitted to your gunsuit - though the cost-benefit of these is both quite critical and hard to parse. Mounting a cheap machine gun as both primary and secondary does the job on the early missions (and has the added advantage of feeling amazing, tearing through the weaker enemies like paper), but the threat quickly outmatches them. Indeed, I suspect the threat quickly outmatches me, too. Right now the game’s escalation of challenge is unforgiving, to say the least, and, if you take a few losses, it seems pretty tricky to pull yourself out of that nose-dive.

At each stage of the campaign’s advancement, you are given a selection of ships to choose for your next mission, each with a different security set-up, time-requirement and difficulty rating. Sub-missions may award you a bonus for completing extra objectives, like capturing the hulk without using any resupply modules or while leaving the door-locking system in place. But after a successful completion you don’t get to investigate the other ships in this cluster - instead, you are immediately advanced to a higher difficulty. Failure, and the destruction of your gunsuit during a mission, meanwhile, only means lost money: you are left to select another mission among ships of an equivalent difficulty. However, if campaign funds go into the red, the entire thing is scrubbed and it’s back to the start screen. I do like that this two tiered failure state exists, but in my experience, a couple of knock-backs ends up costing so much money that you sow the seeds of the campaign’s failure anyway.

One solution would be to allow the player to advance through the difficulty at a speed of their choice, but I can see why the devs might be reluctant to allow this: turtling players might end up investing so much in a single campaign run that they end up truly resenting its eventual failure. Roguelike games have to walk a fine line: keeping the player keenly incentivised on reaching that final goal while making each attempt feel relatively throwaway. Too much commitment to the former is unwise in a game where it’s still possible to encounter ship builds that are, I suspect, nearly impossible to defeat: gamepads will be launched at monitors, for sure.

As it is, Cryptark is one of the most confident entries to Early Access I’ve seen - a few bugs aside, this is robust, generously featured and unusually convincing in its design. In fact, I might well be tempted to use Cryptark as a case study of how to take a simple, hoary old game conceit, like the shmup, and have it transcend into something richly strategic, by ensuring the player has interesting things to consider at every strata of interaction. How you move and what you shoot might occupy you in the moment, but these choices must be folded into your larger plan for the mission, and that, too, into the tricky economics of your campaign. Rarely is good design so easily transparent. Were all Early Access games this competent and complete, I might have to retire the salvage metaphors altogether.

Cryptark is available from Steam for £10. I played Update 0.261 on 07/11/2015.