Elite Dangerous pilots are crossing a dangerous galaxy, and I'm going with them

Approaching the Abyss

Two weeks ago, a fleet of over 13,000 players of Elite Dangerous set out on a long journey to cross the galaxy. Our flyboy Corey Milne was among them.

Asteroid bases always make me feel uneasy. We’re sitting inside a hollowed-out rock, with a single entry gate separating our fragile, oxygen-dependent bodies from the cold vacuum of space. It just doesn’t sit well with me. Yet for myself and thousands of other commanders, the Omega Mining Operation is one of the last safe harbours we may see for a very long time. Two weeks ago, on the 13th January 3305, nearly 9700 commanders took off from the Pallaeni system as part of the Distant Worlds 2 expedition, according to traffic logs. They were all headed to the edge of galaxy. But that’s 65,000 light years away from Earth, and I’m getting ahead of myself. Right now I’m cradling a lukewarm mug of synti-caf in an asteroid’s makeshift cafeteria (a cup of bland Tesco Gold in my living room) equal parts excited and terrified at the journey ahead.

The goal of the expedition is to build a research station at the very heart of our galaxy, near the supermassive black hole known as Sagittarius A*. From there the fleet will head out to the far edge of the galaxy in the hopes of making it to Beagle Point. The famous endpoint of the Distant Suns Expedition.

It’s a daunting task, one you never feel ready for until the moment you get going. In the days leading up to departure I was still agonising over what equipment to bring, swapping out modules of my ship in a bid to second-guess the kinds of situations I could find myself in. Let's see, I’m running a low-emissions power plant to keep my core temperature down, considering my only means of refuelling will be by skimming the surface of stars. It’s bulkier than standard kit, so to compensate I’ve installed lightweight scanners, and my thrusters have been stripped of all extraneous parts. The heavy-duty armour from the ship’s pirating days has been replaced wholesale with a thinner (but lighter) hull.

I might come to regret sacrificing my durability in order to shed weight, but I went after anything that gave my jump range an edge. For a moment, madness took hold and I wondered: do I really need a shield? Visions of my ship shattering against the cold surface of a moon soon put a rest to such notions. Now that I’m out here I couldn’t be happier with my Imperial Clipper, the Roisin Dubh. It’s high maneuverability while in supercruise should see me through most tricky situations (“supercruise” is the faster-than-light travel we have thanks to a ship’s Frame Shift Drive, which means we can travel between planets in minutes rather than years).

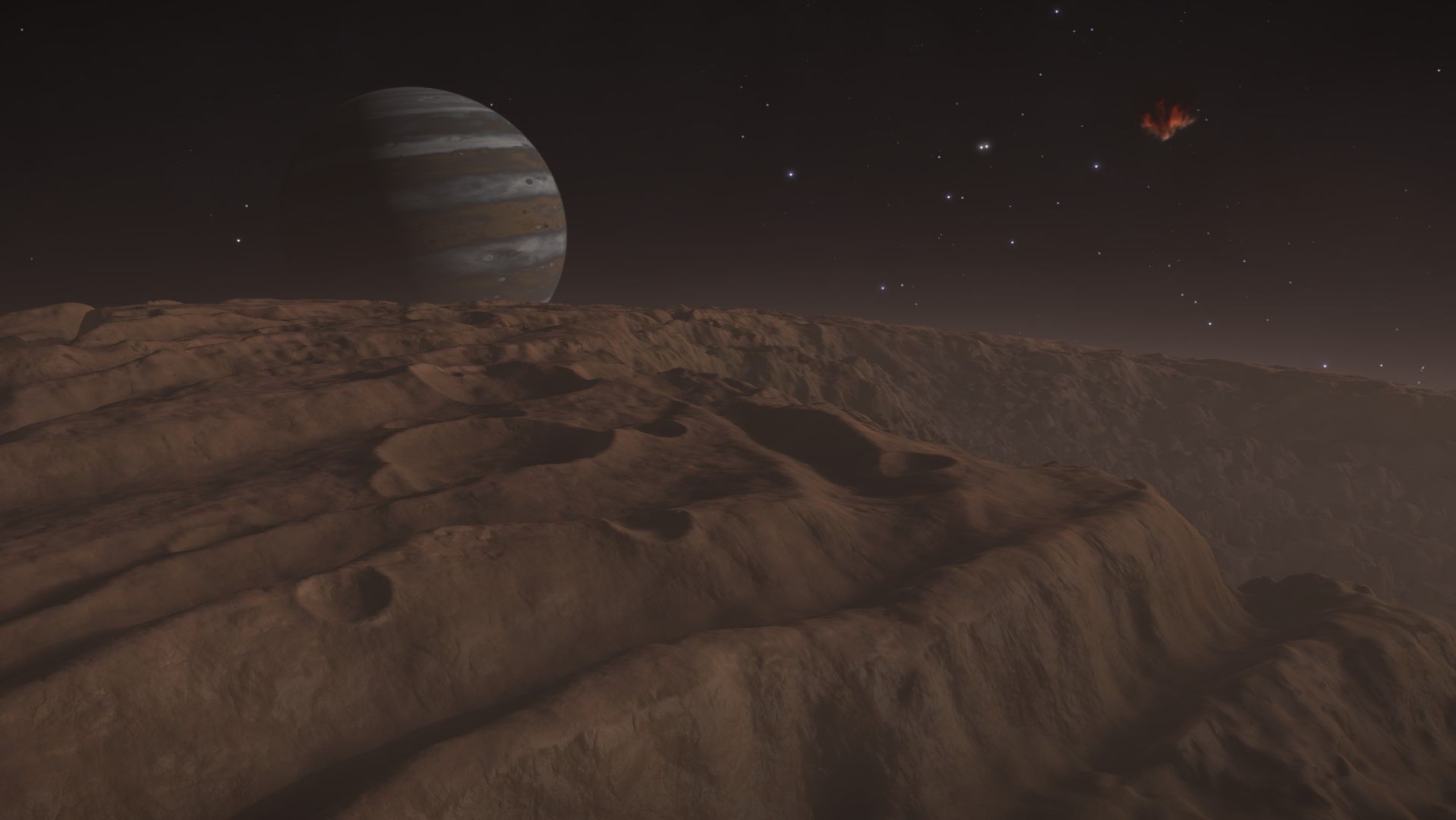

The first leg of the journey seems to have gone smoothly, for the most part. Even though we’ve not travelled very far from the Bubble (the galactic patch of around 20,000 systems that make up the bulk of human civilisation) some of the sights I’ve seen have been beyond what I could have imagined. I’ve flown through the brilliant blast of purple of the Shapley 1 nebula, a single star bathed in a lilac haze. I’ve swam through a field of the impossibly bright, young stars that form the PW2010 Supercluster, while the sheer cliffs of Labirinto’s canyons somehow managed to induce vertigo.

At this early stage, it’s important not to become distracted and remember that space will kill you. It’ll never stop trying to kill you. Sometimes how it kills you will be surprising, like putting a neutron star in an otherwise unexciting route. As your hull melts and your brain presumably boils in the radioactive jetstream, you’ll wish you had kept your now-liquified eyes on the road. Oftentimes, the way space kills you will be very boring, like running out of fuel among a cluster of brown dwarf stars. Your fuel scoop hanging limply in the solar winds, unable to gather the necessary materials from the dead stellar body. As your oxygen depletes and you become part of a new binary system of corpses, you’ll know it was your fault. Space will always be there to capitalise on your inattention, hiding behind the majesty of the cosmos with a knife, ready to drive the point home.

So far nothing has taught this lesson better than the now-infamous system known as The View. Not two days into the trip and we had our first casualties, as the planet’s 3.3gs of gravity plucked unsuspecting ships from the sky and tore them apart. As if the ships were made out of nothing more than paper and dreams. For a long time our communication channels were buzzing with reports of ships coming in too hot. Seasoned commanders were on hand to share advice and offer tips on negotiating high gravity landings. Plenty more joked about having to limp away with only a fraction of their hulls intact. Among all this I took a moment to appreciate the shield generator I hadn’t left behind.

Explorers of all stripes will also need to contend with the overwhelming sense of isolation that can begin to set in after an extended trip into the void. I know this from experience. I’ve returned from comparatively short trips breathless and sweaty-palmed. It’s incredible how swiftly the madness can take hold. The need for a safe port overriding everything else. The longer you’re out there, the more your mind can wander and you envision all the ways your trip could go wrong. You begin to question the point of it all: why should you jeopardise the work you’ve already done by staying out even longer and risking everything? The cartographic data gathered by explorers is extremely valuable information, with extended trips resulting in credit payouts reaching into the tens of millions. Should something happen before you can return home and hand this in, the data will be lost and you’ll return empty-handed.

A few days ago I was idling in the mining camp, refuelling after a brief excursion. I got chatting with another pilot in the hangar through the inter-ship chat channels. Text works better inside an industrial asteroid, which acts like a big echo chamber and amplifies the sounds of big machinery at work. They told me they were equipped to provide fuel and repair support to anyone in need. So far they’d made no rescues, but as they pointed out we were still quite close to civilisation. Of the ships who embarked on the original Distant Worlds 3302 Expedition, less than half their number reached Beagle Point. Even with support teams like the Fuel Rats and Hull Seals, it’s frightening to think of how many we might lose and whether I’ll be among the lost. After all, we’ll eventually have to cross the Abyss. A low-density star field that devours the unwary.

Even if that sense of dread doesn’t get you, perhaps boredom will. Many may find that tuning into radio frequencies to identify planets just doesn’t offer the same excitement as seeing a pirate explode. It can be demoralising when all you seem to come across are low-value icy bodies. When an explorer is on the hunt for virgin water worlds and Earth-likes, every lump of ice becomes a slap in the face.

So why do we do it? Why leave the relative safety of the Bubble? The official goal is of course to establish a new space port that the organisers hope will kickstart a new era of exploration within the galactic core. We’ll also be endeavouring to map as much of the Aphelion, a region of the Centaurus spiral arm, as possible. Whenever I get the chance, I’ve been asking other commanders around the base camps about their motivations for signing up.

One commander told me they’d only be with us for the first part of the journey. They wanted to know what it was like to be a part of a trip like this. That getting to be a part of a multi-ship star jump was an experience they weren’t soon going to forget, but that was enough for them and they’d soon be returning home. Others are industrialists. They’ll be taking part in the community events surrounding the construction of the new research station. Once these are completed they’ll be heading back to the Bubble with their well-earned credits. The biggest reason by far, the one I’ve heard in every quarter, from veteran explorers in fully engineered Anacondas to fresh-faced novices in stock Asp Explorers, is the chance to be a part of a grand adventure.

I can attest to this. I’ll argue no amount of bounty hunting or Imperial gunrunning comes close to the thrill of being the first to find something unusual. I’ve already got a favourite, previously undiscovered star system, Traikoa OE-Z B56-2. It’s home to two ringed planets that are so close to each other that their rings are almost touching. The views from the surface were spectacular.

There’s an immense joy in knowing I’ve added these to our collective star map and that whenever a commander flies through the system, they’ll see my name associated with it. It’s this feeling writ large that drives our fleet. Knowing that we are all putting a permanent stamp on the galaxy and saying in unison: we are here.

It’s only been 2 weeks since we started the expedition and I’ve already seen so much. That they should only be within 5000 light years of the Bubble impresses just how big a trip this is going to be. If this is all so close to home, who knows what’s waiting out there on the far edge of the galaxy. It’s fitting that I should be writing this from a small corner in the Omega Nebula. Previously this had marked my own personal boundary of how far out I’d travelled. It was the end point of my own aborted trip to get to Sagittarius A* last year. That feeling of isolation I mentioned got the better of me, so I turned tail and fled. Now I’m back, and preparing to go over the edge once more, along with 13,000 other commanders. It’s a lot less lonely this time and I’m ready to go on an adventure.

Fly dangerous out there, commanders.