From panel to screen: cartoon cats and visual subjectivity in Blacksad

The cat's miaow

In June 2017 Pendulo Studios, creator of the Runaway series, announced its next project: a video game adaptation of Blacksad, a noir comic starring a feline detective. In the world of games, the news was received with a shrug. But in the comics scene, people were screaming incoherently.

When people think of popular comics, they usually picture some shiny Marvel superhero. But the American comics market is in truth quite small compared to France and Japan, where the most beloved titles sell millions of copies in a year. Sometimes comics reach cult status in their native countries but, due to a variety of reasons (different formats, prices, distribution, marketing etc), barely get any mainstream attention once translated. Blacksad is one such case: it’s one of the most beloved comics in France, mostly known for its incredibly detailed art.

The English version is being published by Dark Horse. You can read it by buying a physical edition, or head to Comixology for a digital copy. The first issue, simply called Blacksad, collects the first three 45-pages issues, while the two subsequent volumes have been published individually.

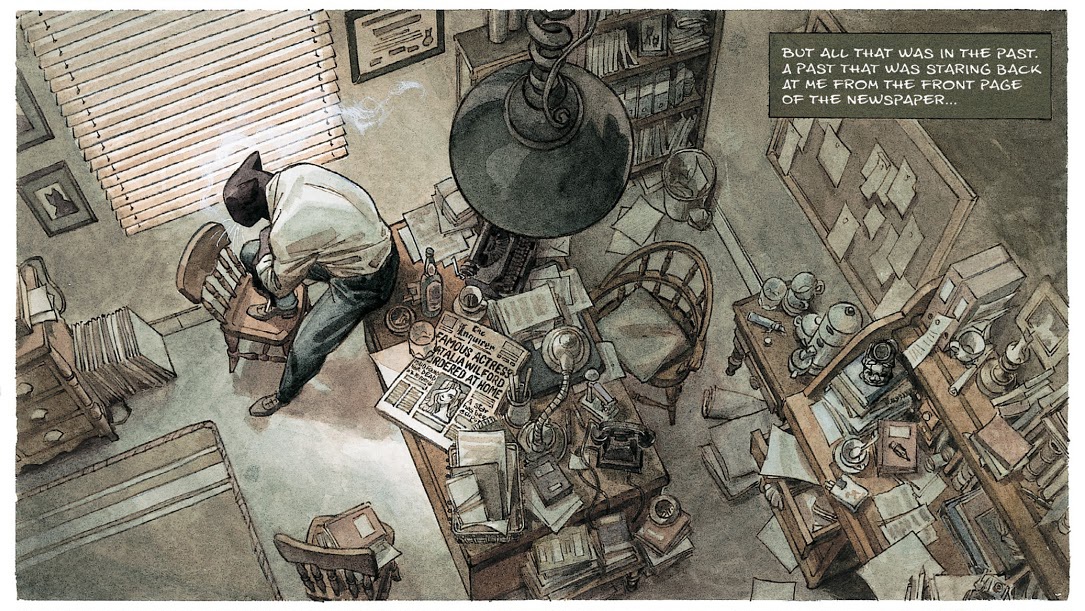

Most comic artists now paint their work digitally, but French readers still have a long-standing love for traditional watercolours. Blacksad is one of the finest examples of the genre: every page is a triumph of finely crafted details, dramatic light effects and expressive animal characters (though I do have issues with the way women are portrayed as sexy pinups with cat ears, as opposed to the more animalistic male characters). It’s no surprise the artist, Juanjo Guarnido, previously worked at Disney. Blacksad’s art style is impossible to replicate on a screen, but trying to recapture its tone will be an even tougher challenge.

Writer Juan Díaz Canales pens classic noir tales about bloody murders and kidnappings, but never shies away from more political topics. Between tense investigations, pub brawls and steamy nights, private detective Blacksad faces the horrors of racism and the nuclear hysteria of post-World War Two America. It’s a past that feels way too present, and I wonder if Pendulo Studios is going to acknowledge those story elements at all.

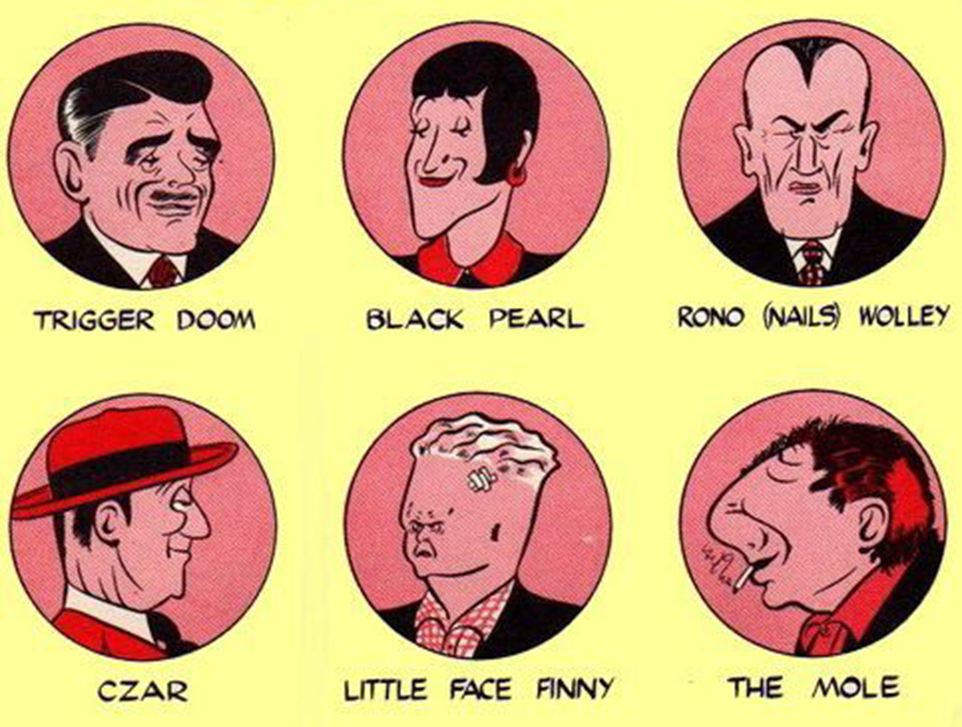

The marriage between cartoon animals and heavy themes may feel counterintuitive, but noir as a genre has always been about larger-than-life characters: damsels in distress, moody detectives in a trench coat, cynic hitmen and cold-blooded villains. Classic noir comic Dick Tracy became famous for its grotesque gallery of villains, all sporting exaggerated facial features that would make Lombroso proud. Using animals to represent such characters only feels like a natural evolution of the genre.

What worries me the most about this Blacksad adaptation isn’t the art or the tone, though. It’s a matter of subjectivity.

The world of video games features plenty of cheerful animal mascots, and isn’t devoid of Detective animals either. Games are full of animals that act like people, but Blacksad is a story about people acting like animals. The setting isn’t a concrete animal utopia like the world of Zootropolis/Zootopia: Blacksad’s characters are humans pictured as beasts because it’s the best way to convey their inner nature. The reality you see between the panels isn’t meant to be objective. The characters should not be read as literal animals.

Video games are little windows into an alternate reality. Our enjoyment of a game is dependent on our suspension of disbelief: the capacity to accept what we see as a believable, coherent space to inhabit. When we read a comic we are not characters of a story, but mere observers — and therefore, I think, it’s easier to accept what we see as an artistic rendition that doesn’t reflect the true status of the world.

Games struggle to deal with the concept of subjective reality. There’s plenty to like in the medium, like the way rabbits in Don’t Starve appear as black balls of fluff when your character is too terrified. But all too often, world-warping mechanics are tied to a, for example, something like a sanity meter - a slippery slope that furthers your vision from the true shape of the world.

Without any elements of nuance, Blacksad is just a cartoon cat.

This idea of subjectivity, and specifically of painting the world through an animal lens to further give empathy to characters, is also used in another stunning comic. Lackadaisy is by Tracy J. Butler, a former veteran of the video game industry now drawing comics about cats leading a life of CRIMES.

Set during the prohibition era, Lackadaisy tells the story of a bunch of smugglers, gangsters and assorted schmucks circling the Lackadaisy speakeasy. They are a charming, desperate bunch trying to survive the sudden death of their former boss, financial troubles, and their own lack of organization, skills and common sense. It’s the happy answer to noir, a comic where most villains are sympathetic and tragedy is always tackled with bittersweet humour. You can read it for free through a variety of digital platforms, like Webtoon or Butler's own website. A physical version is also being published by 4th Dimension Entertainment: you can buy it on Amazon or on the publisher’s shop.

Lackadaisy’s characters may look like cats, but Butler clearly states that this is just her artistic interpretation of the events. She drew human versions of the whole cast, and makes a conscious effort to avoid showing tails, ears and whiskers being touched or interacting with the environment in any way. It may feel like nitpicking, but also speaks of a vision she shares with Blacksad’s creators: sometimes you want to make a comic about humans, but you also want to draw cats because well, aren’t cats neat?

Comics allow you to do both. I’m less sure about what games can do in this regard, but I’m ready to be surprised.