How a comic tried to reimagine cult visual novel Song Of Saya

But what is a monster, anyway?

Seeing Song Of Saya (Saya no Uta) featured on Steam is like finding a dead body on the shore.

It’s a terrific visual novel, this one, but one always recommended in whispers. A horror love story festooned in blood and gore, and with a list of content warnings longer than my games backlog. It can be completed in a single sitting, but will haunt you for years. Its presence on a mainstream storefront feels viscerally wrong, like something dark and rotten that should not have been brought to light.

And yet, this is not the first time Song Of Saya got introduced to a bigger audience. Because a decade ago, it got an American comic adaptation.

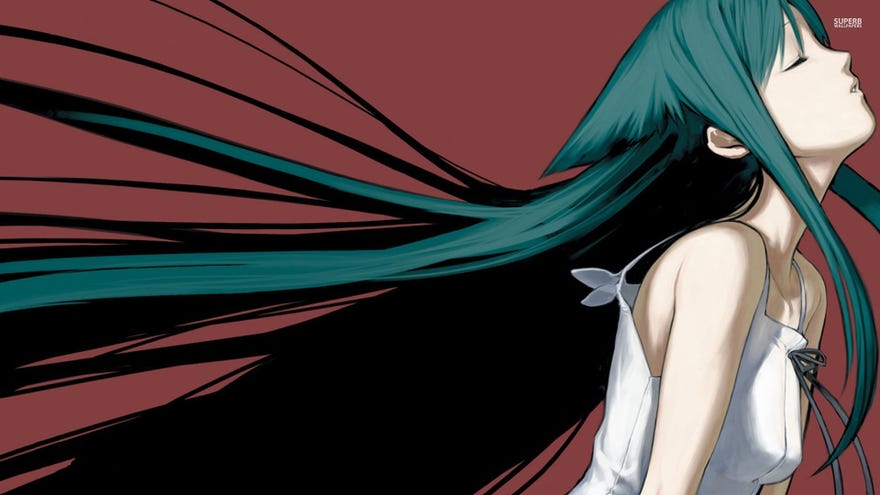

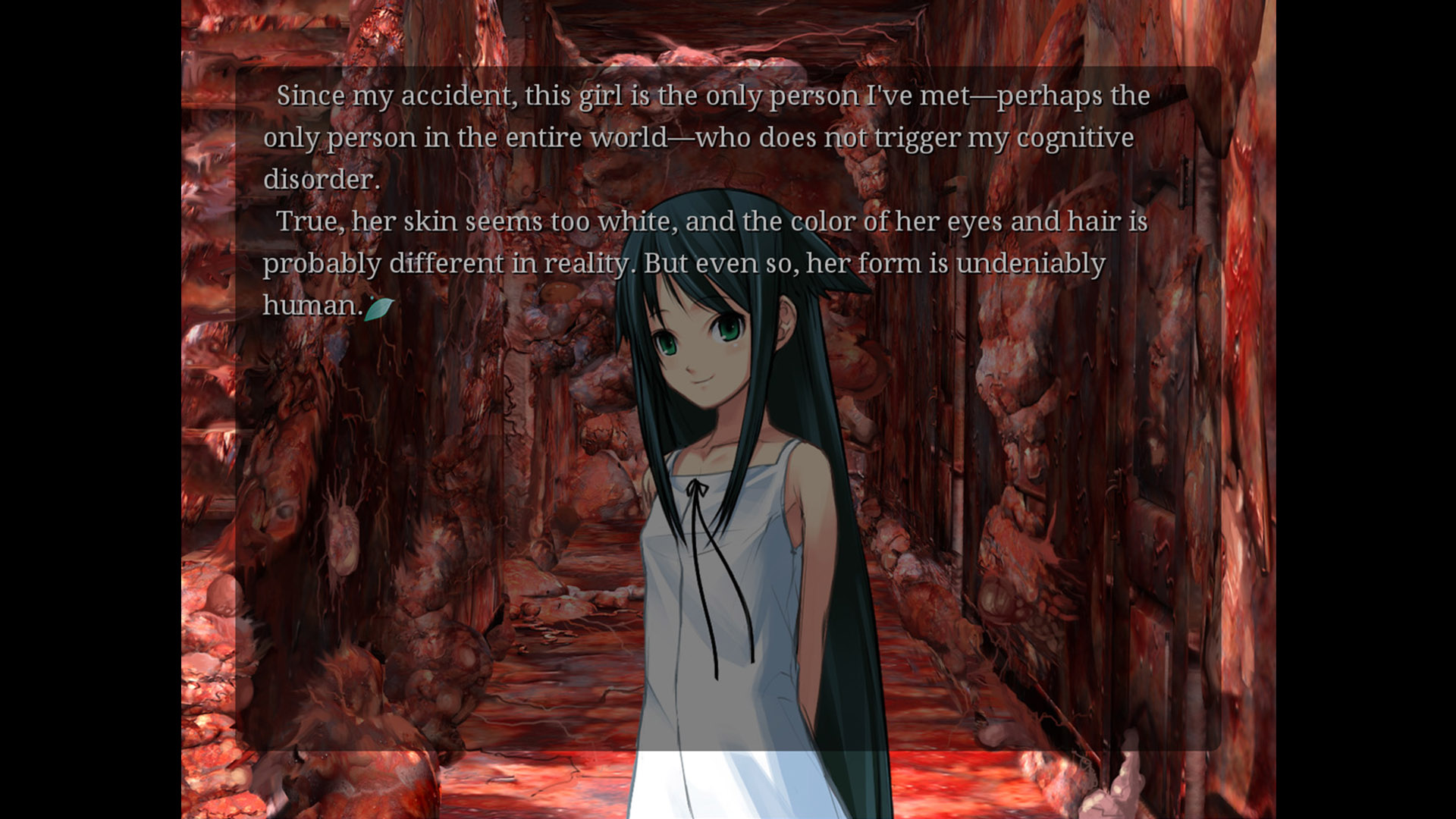

Song Of Saya tells the story of Fuminori, a young medical student who, after a terrible car accident and an experimental brain surgery, finds himself trapped in a living nightmare. His perceptions got all scrambled, and now the world appears to him as a mass of pulsing, rotten gore. The walls around him? Raw flesh. The food on his plate? Wriggling worms. His fellow human beings? Stinking shoggoths oozing pus and blood. His only relief is a girl called Saya, the only person in the world he perceives as a normal human being — but who is clearly something much, much different.

They fall in love. Fuminori's friends start getting worried about his erratic behaviour.

Murder ensues. Cannibalism quickly follows.

This game goes places.

The comic adaptation got published by IDW in 2010, before the game even got officially localized. In an interview for Bloody Disgusting, writers Daniel Liatowitsch & Todd Ocvirk explain how they approached the delicate task of reworking the story "in order to be palatable for a Western audience":

There were some worries that Western audiences wouldn’t accept SAYA as it was. Such as the aforementioned tentacle sex, rape and cannibalism, not to mention the Saya character being underage.

(...) At first, I wasn’t sure what would remain if we eliminated all that stuff. Todd kept pushing for us to try and finally I had this epiphany: It’s an allegory about how far we’d go for love, for that one person who no one else may approve of.

The comic ages up Saya, tones down the violence, and sets the story in a generic Western country. The major plot elements are all there, but remixed and re-contextualized.

Fuminori sees the world as a nightmare. The comic takes the nightmare, paints it with different colours, and gives it a completely different message.

First and foremost was having to make sure things were explained adequately for our Western audience. (...) In the original, we meet Fuminori when he’s already in the middle of his ordeal and you kind of accept the way things are, even though there are flashbacks and some explanations along the way. In our version, even though the bulk of the story is a flashback, for the most part, we see Josh (the protagonist of the comic version) go through the process of losing his mind chronologically.

The gradual descent into madness is a classical horror trope, a staple of the Lovecraftian fiction Song Of Saya so clearly references. The comic's protagonist, Josh, is as an everyday man who leads a perfectly normal life, until sudden headaches start filling his life with horrific visions.

Only Saya's touch can make his hallucinations disappear. The comic version of Saya is as inhuman as its game counterpart, and yet is also framed as the only person capable of slowing Josh's downfall. Together, they fight evil scientists who are experimenting with human brains, because that's evil and wrong. Because despite everything, "normalcy" is still the baseline of their world. Saya might be a monster, but she's a misunderstood one, governed by love and human feelings despite her horrific nature. It feels optimistic, despite all the murdering.

The visual novel, on the other hand, starts when the protagonist has already hit rock bottom and just keeps digging.

Fuminori can't turn-off his meat-o-vision like Josh: everything is always horrible, all the time. The game often shifts perspective between Fuminori and his friends, showing the same scenes from different point of views to really hammer home how warped Fuminori's situation is. His relationship with Saya is one born out of despair; they don't have anything but each other, and the whole world is against them. The enemies who want to hurt Saya don't want to kill her because she's evil, but because she's wrong. Unnatural. An insult to the natural state of things.

Fuminori clearly states he has no trouble killing his former friends, because he doesn't consider them human anymore. How could he? We see how he perceives the world; see how disgusting everyone appears to him. He protects Saya simply because she's the only one he can perceive as human.

(I wonder if Fuminori would have loved her anyway if she had appeared as an ugly, elderly woman.)

His comic counterpart Josh aspires to be a more relatable protagonist; an everyday man holding onto madness. And yet he appears less sympathetic, because his moral compass is still there. Because when he attacks humans to protect his Saya, he sees them as human beings, not monsters.

Song Of Saya, the visual novel, asks us: "would you consider someone less human just because they look ugly?"

And it's such a chilling question because the answer is "yes"; because we all know, deep down, that we react with fear to whose who look different than us. Because for our whole lives we played games and read comics where the villains are ugly, deformed and monstrous, while the heroes must always look neat.

Lovecraft told us all monsters are ugly. Song Of Saya tells us people make monsters of those they don't consider beautiful.

What does it even mean, to "westernize" a Japanese visual novel? To change the setting? To remove cultural references that are deemed weird or less socially acceptable? To rearrange the story, following common movie tropes, so it will feel more familiar?

To make it look less foreign because people are racists?

The comic version of Song Of Saya does all this, and yet I am not sure it accomplished what it wanted to accomplish.

Can you really twist a story to make it more palatable, when said story has never been meant to be palatable in the first place?

In an interview for Anime Jump, producer Yasuyuki Ueda talks bitterly about his anime series Serial Experiment Lain. He had hoped his work would have been interpreted differently by Japanese and American fans, sparking a cultural "war of ideas" between different fandoms.

But fans from all around the world interpreted his work in the same way, leaving him disappointed.

I'm glad that everyone likes Lain! But at the same time, I kind of wonder, do people over here really understand Lain? The way I perceive things, the way Japanese viewers perceived Lain would be different from how Americans viewed it. But when I was in L.A., the fans I met seemed so very Japanese in their perception... and that kind of isn't what I wanted, because like I said earlier, I wanted there to be a clash between cultures. I wanted American fans to see Lain and think, "No! That's screwed up! That's so wrong!"

I am but a simple weeb. I am not really equipped for a deep discussion about cultural differences between Japanese and American fiction.

But sometimes I think we focus too much on our differences, forgetting that we're all humans after all.