Race Around The Clock: Remembering Street Rod

No Need For Need For Speed

I didn’t have a car when I was a teenager but I did have a Commodore 64, and it was as temperamental, arcane, and hard to get working as anyone’s first used car would be. A hand-me-down from my stepbrother, it came with a pile of dubious floppy disks, plus a few cassettes that rarely worked, and one of those floppies had Street Rod on it.

Street Rod is a game made in 1989 and set in 1963 but nostalgic for the 1950s. It's also, by dint of its marriage of street racing with plot, mundane car maintenance, and the time limit of a single summer, a more progressive and interesting forebear to the modern Need For Speed.

The game takes place over a summer when JFK was still alive and The Beatles hadn’t arrived in the USA, so its America is still an innocent place of slicked-back hair, leather jackets, and muscle cars. I’m pretty sure everyone in Street Rod has a packet of cigarettes twisted up in the sleeve of their T-shirt. You play a kid from Los Angeles with $750, access to an empty garage, and an entire summer vacation to rise through the ranks of the local street racers until you defeat the coolest of them: a guy who wears sunglasses at night, drives a black Corvette, and is known only as The King. If you beat him you become the new King and get to date his girlfriend, as is written in the Constitution.

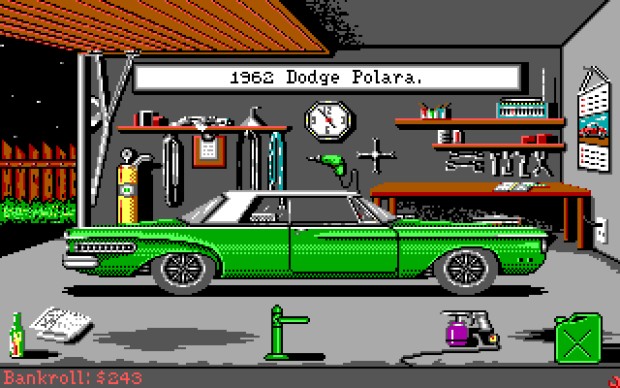

There’s a story to Street Rod, but one implied in details. You learn about the protagonist’s circumstances because you begin the game browsing the used car section of the newspaper and can only afford vehicles from 20 years ago. I rocked up to Bob’s Drive-In for the first time with a 1940 Chevrolet Coupe, which made guys with names like Biff sneer when I challenged them to races. There were two things on my side in those early races, though. The first is that I cheated like a bastard, slamming into opponents then pushing in front while they reacted, hogging the road in my fat American beast for the rest of the race. The other is that I upgraded its V6 engine in ways I still only notionally understand.

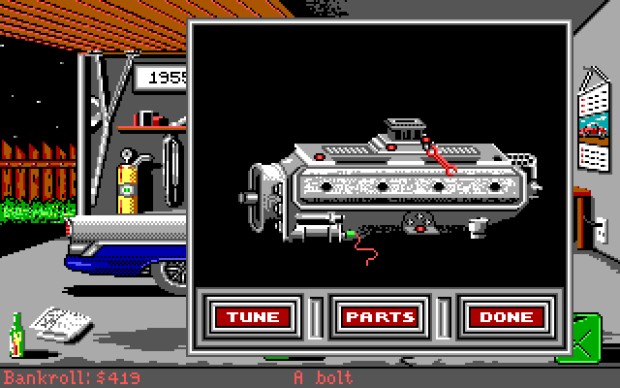

Upgrading in Street Rod isn’t a matter of buying new parts and watching them sprout from your car like sped-up footage of mold on bread. It’s also not about earning experience points until your car somehow learns to handle corners better. You have to get your hands dirty. You replace parts by searching newspaper classifieds for bargains and then adding them by hand. You pop the hood and tinker with engine guts as they tick over until you hit a sweet spot that makes the tinny internal computer speaker approximate the humming of a well-tuned machine.

The workings of an engine may as well be actual necromancy to me, but somehow I managed to pull the two-barrel carburetor off (clicking on each bolt twice to unscrew them), and then removed the manifold that housed it. I replaced that manifold with one that had room for three carburetors and then added two more just like the original, all sourced from the same newspaper as my car. I’d overclocked that V6 engine, which surprised the hell out of Biff when I left the big jerk behind.

Street Rod wants you to get to know your car the way a fascinated first-car-owning delinquent would. The transmission can be pulled off and replaced, again by clicking on all the screws one by one. The bumpers come off, giving a tiny increase to speed at the expense of durability. The roof can be chopped down for a slicker profile and maybe a slight aerodynamic boost. All these things happen because you point your mouse at the appropriate section of the car, and only when you need to swap in a new part does a menu intrude.

Street Rod is so grounded it expects you to fill the tank between races by dragging a gas pump onto the gas hole or whatever it’s called, wait for the tank to fill up and drag it back again. So many things that would be elided in a modern game are modeled here, right down to wear and tear on your tires and engine. It feels like a survival game, only instead of your character needing to drink water at an unbelievable rate you have to pour endless fuel into your car because that’s how these all-American behemoths worked.

Street Rod is also a racing game, obviously. There are only two tracks: a straight drag strip and a curving, hazardous road race on the edge of town. Like a MOBA with only one map the point is to make you focus on the characters instead, but instead of a hundred different wizards Street Rod has 25 cars with names just as extravagant. Plymouth Valiant. Pontiac Silver Streak. Mercury Monterey. All of them handle differently, but since Street Rod is designed for keyboard you drive them the same way: always accelerating or decelerating. It forces you to drive like a lead-footed teenager.

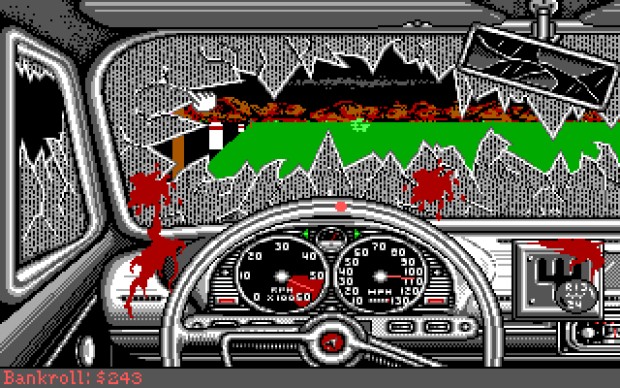

When I crash the glass shatters, and sometimes there’s blood. Sometimes I repair the car, sometimes I sell it for scrap, and sometimes I have to reload. I get better though, and the amounts wagered on races increase until they become “pink slips” – ownership papers – with the winner taking home the loser’s car to keep or sell. The money piles up and the cars get faster, and suddenly Bob’s Drive-In is full of challengers who own vehicles right out of Mad Max, with flame jobs and engines popping out like mechanical chestbursters. To impress them so they’ll race me I’ve repainted my car and added a rad sticker to the side that says “I’m not a cop” as the next desperate steps in the race to the top. The days are ticking by, and summer’s over soon.

Time limits in games are often a frustration. When you catch a getaway car in Driver: San Francisco but don’t manage it inside an arbitrary three-minute window and have to repeat the whole chase, that’s an annoyance. But the kind of time limit that adds significance to what you do – like the one that makes the final mission in Mass Effect 2 harder if you put it off – those I have no problem with. Knowing I had 150 days to complete Fallout pushed me to more dramatic, risky decisions than I made in the sequels. So I don’t mind Street Rod’s summer vacation ticking away, days vanishing from the calendar in my garage, because it urges me on, makes me incautious. I drive like a maniac in race after race until the transmission falls out the bottom of my new Dodge Polara like a bomb.

Anyway, the whole point of summers is that they end, and then we grow old and turn nostalgic. Fortunately I can indulge my nostalgia for Street Rod even without that Commodore 64, because the current rights holder has decided to give it away for free. You can download it from streetrodonline.com, though you’ll need DOSBox to get it running on modern PCs. There’s also a sequel from 1991, though I prefer the original. The main difference is that Street Rod 2 has extra tracks, one on Mulholland Drive and the other an aqueduct straight out of Grease, but both have hazards that force you to regulate your speed with exaggerated precision rather than hooning through them like a dangerously hormonal greaser. Also, there are no longer stickers you can slap on the side of your cars.

Both adult me and the kid with the Commodore 64 would rather be a greaser with “I’m not a cop” on the side of our two-door sports coupe.