The first CRPG is a min-maxing hell you can - and should - break

Let me tell you how to play Ultima 0

1979’s Akalabeth: World Of Doom, eventually renamed Ultima 0, is the first commercial game by Richard Garriott (himself aka'd Lord British), and one of the very first roleplaying video games to enter the market. It’s also a precursor to Garriott’s Ultima series, introducing many elements that formed the core of the following games. But everything that Akalabeth invented would eventually be abandoned, first by its sequels and then the entire RPG genre.

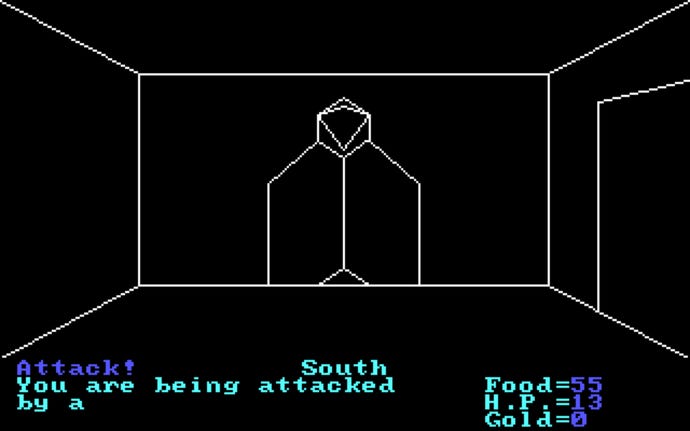

Your most important resource in Akalabeth is food, as running out for even one turn will result in a game over. It doesn’t slowly drop your health, it doesn’t cause negative effects, it just kills you. Nowadays, survival mechanics so extreme only exist in mods and dedicated subgenres, but in early ’80s RPGs this used to be the norm, and Akalabeth is riddled with classic mechanics that have since been abandoned. Other examples include first-person dungeon exploration, an unbalanced class system, and a control scheme stuck between CRPG, dungeon crawler, and text adventure.

But there’s at least one element of Akalabeth that is still relevant today. Most of the game, from character creation to dungeon crawling, is incomprehensible without help, and looking for it on the internet always reveals an amount of knowledge that doesn’t feel appropriate for human minds. There' s no playing Akalabeth just like they did in 1979; it’s too late for that. What you can do is break it, as they did in 1979. After all, you just have to follow instructions. Which I'm going to explain to you now.

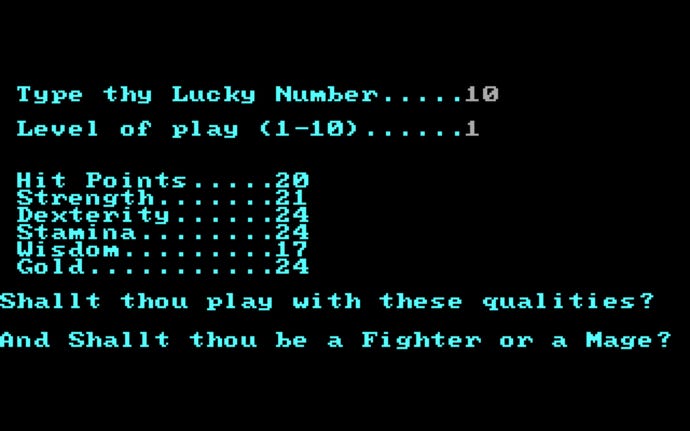

When starting a new game in Akalabeth, you will make exactly five choices. After selecting the game’s difficulty and a mysterious “favourite number”, you will create a character by rolling ability scores, selecting a class, and buying your starting inventory. In order to make your playthrough a successful one, you’ll have to understand and manipulate every single one of those categories.

Your first Akalabeth playthrough will likely end with a hero who starved to death before finding a single dungeon. Travelling around the barren world map costs food, and it’s not cheap either. This uniquely dangerous risk of starvation will likely be the end of many heroes after your first, even as you start buying all the food in the shop. The solution to the puzzle is to stick with the same favourite number - which, it turns out, is responsible for generating the game’s map. This allows you to use the layout of the overworld to your advantage, minimizing movements between the shop, the dungeon and the quest giver’s hut.

But your favourite number is responsible for a great deal more than the map layout. The random selection of character stats that you roll during character creation isn’t random at all: each of those results, including the ones you get by re-rolling the virtual dice, are pre-determined by your selected favourite number. Your next step should be to start with better stats, so you might have to switch your favourite number once again.

The last decision you’ll make is the most important, so much so that it isn’t a choice at all. There are two available classes, and while the warrior gets marginally better weapons, the mage is the only one who can use magic amulets with ease. Magic in the world of Akalabeth works in weird and convoluted ways. Amulets can move users up and down dungeon levels without using one of the hidden ladders. They can even kill an enemy instantly. But even that’s nothing compared to what the transformation spell can do.

Sure, the warrior’s weapons do slightly more base damage, but mages can turn themselves into lizardmen and raise all their attributes by 250%, including those governing bonus damage. The lizardman effect is permanent, only consumes one amulet, and it stacks across multiple uses. Even if it can backfire, a bit of save scumming removes all possible risks involved. In practical terms: the best possible stats for an endgame warrior are 35 across the line. A mage can reach 1000 points right after their first dungeon with only a handful of amulets and a bit of luck. You’ll kill everything in one hit, avoid all hits yourself even if something survives, and have enough food to last you for tens of real-life hours. The mage doesn’t need the warrior’s unique weapons, it can just use its lizard fists.

Some players might think that beating Akalabeth this way on your first through is cheating. It's not necessarily a wrong approach to the game, but it's not how the game is supposed to be played either. But is that so different from basing your Baldur’s Gate 3 character on someone else’s build? From following the advice of experienced players for your next World Of Warcraft character? RPGs are often based on complex systems that are rarely taught before the start of the game, and Akalabeth is no exception. Reconciling with those systems, from character creation to the best combat strategies, is part of the appeal of the genre. Some players study the manual, some go through trial and error, and others like using a guide. This goes for Akalabeth as much as for any modern game.

In Baldur’s Gate 3, which is based on the 5th edition of Dungeons & Dragons, the challenge comes from the complexity of its tabletop counterpart, and while the mechanics of Akalabeth are simple, the explanation itself is what's much lacking. The solution that unites them is to imitate the strategies of other players, min-maxing your way through the game and skipping the intricacy of its system.

The most familiar interaction we can have with a game so different from our modern standards is to break it. We might not understand how or why we’re doing it, but that’s fine. Contrived and unintended though it may be, min-maxing your way through Akalabeth as a hench lizard wizard is how to play it like it was played back in the 70s.