The Joy of Kimmy’s childish dialogue

"You're mean, like 10 snakes"

When young Dana meets Kimmy, she assumes that the 6-year-old must be a baby sent from the almighty. God gives people babies after all, according to Dana’s mother. This kind of naive understanding defines Kimmy, a visual novel based on tales from the developer’s own mother and narrated primarily by children. The premise is as simple as its dialogue. Set in 1968, it follows a young girl, Dana, as she babysits her neighbor, little Kimmy. The pair teach other neighborhood kids new street games in an effort to coax the shy Kimmy out of her comfort zone and make friends. But the joy of this story comes in how its characters talk to one another.

Both Kimmy and Dana reflect their problems through the lens of their limited knowledge about the world, a world in which they discover new facts, emotions, and relationships every day. When Kimmy says she has no friends, Dana points to a neighborhood girl nearby and responds with a chipper “Well, let’s become her friend.” When Kimmy’s mom is behaving in ways she can’t explain, sulking half the time and irate the other half, she surmises that her mom must be tired, the only point of reference she knows for such behavior.

These pithy observations carry the most weight when the children face more complex problems like, say, a parent’s tendency to drink too much. Kimmy’s father often fails in his parenting duties when watching her sister, Mal, and starts tipping back beers, leaving the baby alone for lengthy periods and slipping into a furious mood. “He probably messed up again,” Kimmy explains as they come home to Mal by herself. You can hear the hurt disappointment in her words even as she struggles to put a name to the complicated emotion she’s feeling.

Many of the children on the block share similar stories of neglectful, drunk fathers, and though you never see any of any of them in-game, their actions weigh heavy on their childrens' minds. “Grown-ups never get in trouble even when they’re bad,” your friend Blythe says. “We need teachers for adults so everyone gets yelled at,” she adds, using what little reference she has to articulate the injustice she sees. The world is divided between bad and good, grown-up and child, dichotomies built by children when their words fail them, because to draw a line in the sand makes things make sense, and in the middle ground confusion reigns. Not that different from how adults see things, come to think of it.

Though for these kids, the complex, mind-boggling debacles of day-to-day life get boiled down into terse sentences devoid of the adjectives and adverbs adults have built up over time to make our speech more palatable. Their limited vernacular often gets to the truth of things better than any adult could, but it also curtails any attempt at expressing themselves fully.

Sometimes this failure proves hilarious. At one point, Kimmy tires of Blythe’s teasing and tells her “You’re mean like 10 snakes.” It doesn’t make sense, and Blythe tells her as much, but no doubt it’s the absolute worst thing her young brain could think to be.

For the most part, though, their combined lack of emotional intelligence and vocabulary proves heartbreaking. “It’s hard to play when mom and dad are so angry,” a weary Kimmy says in the middle of a game with her friends one day. “I feel like I can hear them fighting even if they’re not here.” She has absolutely no clue what the problem could be and has come to her own tentative conclusion as to why they’re angry, as children often do. She doesn’t want it to be true, though, so she instead poses it to the group: “Do you think people can be born mean?”

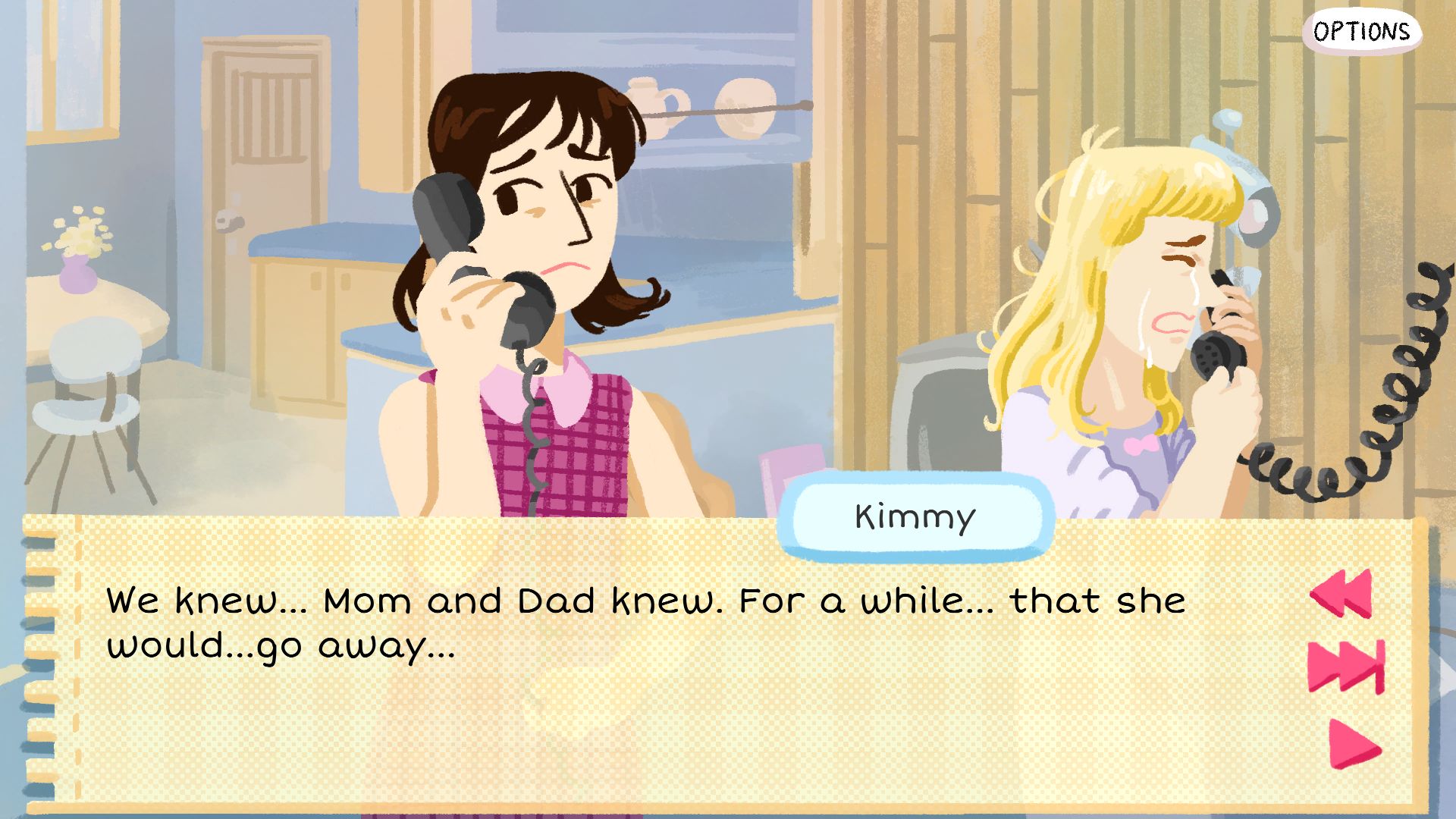

It’s such a simple question that could only come from a child (especially impressive when you remember Kimmy’s developer is the, of course, adult Nina Freeman, the creator of Cibele). In truth, her parents are fighting because their second daughter, Mal, is slowly dying from an unexplained illness, and though Kimmy shows signs of understanding some pieces of this, she can’t possibly grasp the whole situation. With what she does understand combined with her truncated worldview, it’s a perfectly logical conclusion.

And when Mal ultimately succumbs to her illness, Kimmy doesn’t have the words to even explain why she’s upset. “Mal left because she’s sick,” she cries into the phone while talking to Dana. “I feel sad...or something worse…” Her parents moved her to a new home after the ordeal, and now she’s alone in a new place, far from the friends she’s only just made, and the only words she can think to put to all her sorrow is “worse than sad.”

When Dana leaves her home sobbing after hearing the news, her friends hardly know how to stop her to tears either. They ask if she’s upset, but don’t have a way to help when she answers. Even if they did possess the maturity to try to console her, some problems, as adults know far too well, can’t be solved by simple comforting words.

So, faced with a problem they don’t understand, they respond with the nicest thing they can think of; “Do you want to play” becomes an offer of compassion, “Do you want to learn a new game” the only olive branch they know to extend. Dana behaved similarly when initially hearing the news. Her first thought was to offer to babysit soon, to ride her bike to Kimmy’s new home, wherever that may be, and to play with her again.

Distraction is what they know best to ease away the tears, and ultimately, distraction becomes Dana’s path to healing. “Summer ended. School started. I eventually forgot,” she muses in the game’s ending sequence. Soon, the sting of Kimmy leaving dissolves into a half-forgotten tale she tells her daughter on a car ride one day, much in the same way Freeman’s own mother recounted growing up in the ‘60s and whose stories inspired Kimmy’s creation.

While the children in Kimmy don’t know the words to express how they feel, that doesn’t keep them from trying. Despite this hurdle, most of them get to the heart of things with far fewer words than adults, and they speak their truths unmuddled by niceties and pretty language. And when words fail them, as they often do adults, actions take their place, so that the single nicest thing you can do for a sad friend becomes a simple offer to come out and play.