Sound Garden: The Aural Landscape Of Fract OSC

Audioturf

This is the latest in the series of articles about the art technology of games, in collaboration with the particularly handsome Dead End Thrills.

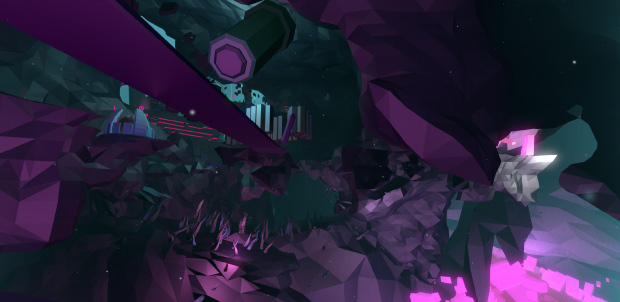

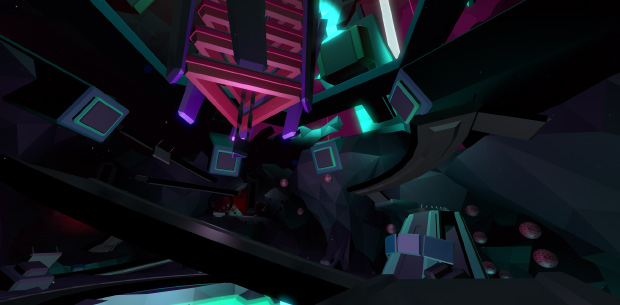

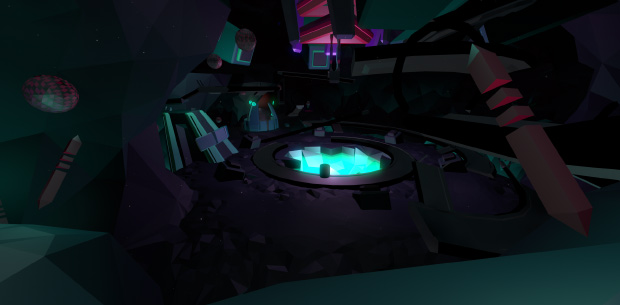

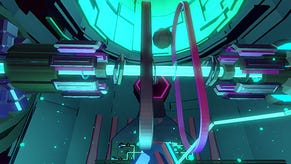

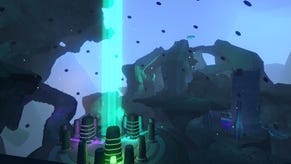

In the Tron-like synthesiser world of Fract OSC, dead code awaits the healing touch of the user. Towering polygonal geodes hide the tools for making music, and somewhere in each vast structure is a way to power it back up. Bringing it back to life, though, is often the other half of the puzzle. For that you'll have to compose.

Phosfiend Systems' first 'proper' game comes via an IGF award-winning prototype, backing from the Indie Fund, Steam Greenlight, but most importantly creator Richard Flanagan's passion for synthpop and its hardware. His background in web and analogue game design doesn't hurt, either. Indeed, perhaps the most striking thing about Fract OSC is how its synaesthesic interface - text and prompts are swapped for directional lasers and electro power chords - gets equal billing to its puzzling and exploration.

DET: What rules did you set yourself for Fract's world?

Richard Flanagan: Some of them certainly were deliberate artistic direction rules, some were also pragmatic because we're a small team. I always wanted to do something highly polygonal, and I'm really interested in the apparatus of communication - whether it's a computer or a book or what have you - being really honest about what it's doing, what it represents. Some people do a fantastic job of covering up the polygons, but I felt it was a very honest way of saying this is inside a computer. Geometry like this doesn't exist outside of a computer.

Computer graphics are weird and they've evolved in a weird way, and for some reason we're doing stuff with polygons. I dunno, I wanted to celebrate that.

From a pragmatic perspective, as the person who's building all the stuff in the game, it means I don't have to spend eons doing it, and I can use somewhat parametric tools to try and build these large, interesting structures in a quick way.

Finally, from sort of a game perspective - and this has been a tricky one to balance in terms of aesthetic, interaction design, and just guiding or not guiding the player - there's this idea that the world is alien but decipherable. That's been a key component to massage some of these things into their aesthetic.

DET: How did you connect up such a vast, modular and abstract landscape?

Flanagan: It was brutal. I feel like we only finished cracking the exact structure maybe six or eight months ago. There's a lot of fanatic aspects to why certain things are in certain places; as a designer I like to imbue things with a sense of 'why'. Admittedly, 95 per cent of that is going to go unseen or not really questioned, that's just the way it is. But I think it's important when designing a system to ask that why. Why am I putting this here? Why is this purple and that pink? I don't think those answers always have to be profound, but I think we need to ask them. I was a long process, for sure, and it was pretty painful. This iteration that you've played is arguably the fourth completely new version of the world.

DET: Why embark on such an ambitious overhaul after the beta?

Flanagan: I think there's a lot of charm in that first prototype. It was the first time I'd used any of that software so there was definitely a learning curve. Why did that get tossed? Because it was held together by toothpicks and bubblegum, and when we brought a technical person into the team I knew we'd have to throw it all away. It was just ridiculous. But it still showed a glimmer of that world I wanted to bulid, and I think it was a really solid sketch. There's still aspects of it I really like that, to be honest, I don't think are fully present in the new one. But it's a new piece, it's new work.

DET: How much does Fract's audio shape the visuals and vice-versa?

Flanagan: It's been remarkably iterative, actually. We've been tweaking our audio tech forever but it's been largely in place for the better part of a year. I've talked to some other devs and they ask how it's going, and I'm like, 'Oh, just working on some puzzles, still tweaking the audio.' And they're like: 'What do you mean? I thought the audio was done.'

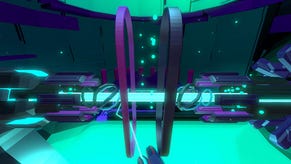

It's been interesting because the audio is so intrinsically connected to the mechanics of the puzzles that if we tune something mechanically in the puzzle, this alters the audio. And if it alters the audio, because many systems are plugged into what the audio's doing that react visually, we're going to have visual changes. Which is super exciting. The game surprises me with audio and, sometimes, visual reactions. Again, this is probably my first real game so maybe I should have expected this kind of back and forth, but often changes to one or the other would require a rethink. We went through some pretty big creative changes.

We did a dev diary about two years ago where we promised that we were going to teach people how to make music, and how to understand synthesisers. I've been into synths for 15 years and I'm still learning new stuff - it's too complicated. So we started scaling back what our goals were, which was terrifying. I felt like this was a huge failing on my part, that I wasn't designing the experience I was supposed to be. It was a huge crisis of confidence. The player was being given these hyper-abstract ideas without any text or UI, in a 3D world, and it was failing.

It's really intimidating to walk into a music shop. There's a really cool music shop here in Montreal that sells all kinds of modular gear, and even I go in there and go, 'Oh man, I don't want to touch anything, they'll know I'm a fraud.' So now, instead of teaching, what we want to do is just act as a primer. This has had a profound effect on the audio, this simplification of what the player's doing. The engine is still hyper-complicated and simulating an analogue synthesiser or ten in the background, but what that did is change the auditory presentation. It became fun again, just tweaking knobs, solving puzzles and making sounds. And not necessarily hyper-static sound and music, but music that is a result of your tinkering or that, depending on the time-of-day cycle in the game, maybe you're never going to hear again.

DET: What does the time of day cycle do exactly?

Flanagan: Various objects in the game respond to a number of background parameters. I wouldn't call it super-obvious, but hopefully subtle enough that if the player pokes around in a spot they didn't before, they might discover differences.

DET: You have a web design and UI background, the value of which is easily underestimated for game design. How did it help you with Fract?

Flanagan: There's a lot of transfer, especially when it comes to UI. I'm a huge UI dork and could just design interfaces and be reasonably happy till I'm dead. There are aspects of web I enjoyed and didn't, but UI is such a delicate - I don't want to call it an artform because it's a lot more than that - design. You have to consider your user, people's attention span - and in the web that's seconds. I've heard people talk about studies and suggest that it's many seconds, even minutes in games. Well that's a huge difference. In the web you've maybe five or ten seconds to keep people moving and interested. I think that does really help.

You want to simplify but at the same time - at least in the case of Fract because we're not using text - make it interesting enough to use, but not obvious. Coming from graphic design in general helped develop that 'why' I mentioned before. If I'm going to put these buttons on the left, why? Is there a convention? An expectation? Is it more ergonimic?

DET: The sense of scale has dramatically improved, not just in geometry but also effects.

Flanagan: It's something that's still causing us challenges from a technical perspective. We'll get it running well, but having a big world and trying to render everything all the time-- But I guess that comes back to this romantic connection I have to the transmission mechanism being honest about what it is. I love hallway shooters, too, but why aren't we making huge things? There's no limit to the space we can make, it's all vector and completely virtual. I really like the idea of big scale. It's not trivial to make that stuff feel and flow great, and there's a bit of work to be done there. But for me that always seemed like a no-brainer: 'It's gonna be big 'cause it can be.'

DET: What was the biggest thing you couldn't do?

Flanagan: There's an underlying idea of interaction design I'm really interested in, about how we interact with things and learn while we're using something unfamiliar. It has to do with hierarchy of scale. I don't know if I'm going to nail this idea in this game, but I would have liked to have had another layer. I'm sure that if we had more time, money-- I'm sure the tech must exist to literally fold an entire open world on itself. Maybe that's a bit literal for what we're trying to do, but I wish we could have pulled an Inception or something at the end.

DET: What about the analogue effects in the game? The 'scratching' as you run, or the CRT filter?

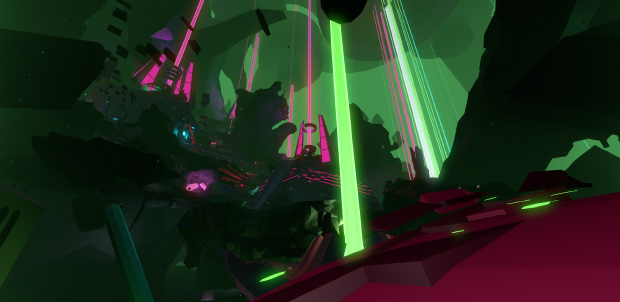

Flanagan: Well, it is a very digital space but the inspiration for this world was analogue synths, and an era for those that's having an amazing resurgence right now. It's the second golden age of synthesisers, which is blowing my mind. When I started this project three years ago, no, but now you can walk into a music shop and there's like five new synths. It's crazy.

Fract was inspired by these tools from a different time. They were complicated in a way, but compared to the digital workstations now that have a 200-page manual... I found a copy of the manual for one of my analogue synths, and it shows a guy with this electric guitar plugged into the back of a synth, and he's smoking something. This is a manual... from Japan. It's just a different era. And of course the CRT era is when I played the Mysts and the adventure games. Some of it's nostalgia, but some of it's to acknowledge that transitional era when we were between analogue and digital.

DET: How intentional was the feeling of being lost in Fract?

Flanagan: I'd say it was almost exclusively intentional. It's always been about discovering and trying to decipher this world as you explore it. I joke about it internally but very realistically call it a kind of archaeological tourism simulator, because it's about that uncovering, digging around. It very directly paralleled some of my experiences in discovering new types of music and music production, and when I first discovered music-making tools about 15 years ago now. These were democratic and awesome tools, and I had no idea what any of it did. I was just walking into this world; didn't know what music I wanted to make, but did know I wanted to poke around. And it's great that more and more of this is happening. I've been fortunate enough to play a fair amount of The Witness, and it's so good.

Alienate is maybe too strong a word, but I want people to wonder: why does that thing look like it's talking to that thing? What is this thing? And then they develop an ownership of the choices they've made, and this hopefully becomes more apparent when they solve puzzles by writing their own music.

DET: What architectural references did you turn to?

Flanagan: There are a series of architectural sculptures in the former USSR called Spomeniks. They look like they belong in another world, or in Tron. And they're almost all created by completely different artists and architects, but they're so fascinating. They're not just interesting from their form but because of the curiosity. 'Why is this here? What is this doing here?'

I have another little book I flick through pretty often, of a Japanese architect called Tadao Ando. Some of his stuff has been really interesting. Big cement forms, lots of interesting light. I'll say 50 per cent of that is very intentional, that sort of gradient of hyper-abstract to not abstract; and some of it is the fact that we've been making this game for a couple of years, and I think that my techniques have evolved a bit. Some of that is present in the game. But when in doubt, my wife's really good at coming in and saying, 'Mess it up some more. Make it crazy.' Which is a good influence.

Fract OSC is still in development and has no release date, but Phosfiend promises an announcement "very shortly". The 'OSC' is short for 'Oscillator', by the way, a hangover from when this latest Fract, now a full game, was episodic.