Level With Me, Richard Flanagan

Sound And Solidity

Level With Me is a series of interviews with game developers about their games, work process, and design philosophy. At the end of each interview, they design part of a small first person game. You can play this game at the very end of the series.

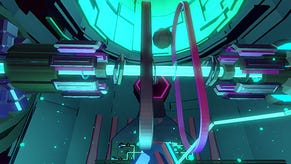

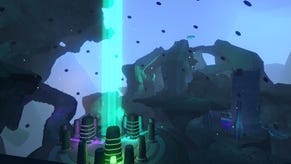

Richard Flanagan is the main designer on FRACT, a first person exploration puzzle game and/or electronic music studio. He collaborates with his producer and/or wife Quynh as Phosfiend Systems, based in Montreal, QC -- they've also been working with indies Henk Boom and Devine Lu Linvega.

Robert Yang: So how are things?

Richard Flanagan: It's coming together. Everyday, the screws get tighter. It's mostly about the time, now. I don't want FRACT to be like a five year project.

RY: Wow. I've never worked on a game for that long.

RF: Let's see... I did the first prototype at the end of 2010.

RY: It's a different game now.

RF: Fuck yeah! Completely different. We've been working on *this* FRACT for like 2 years. Now it has three sections, and in these sections we've just found a UI exploit that breaks lot of puzzles, so right now we're fixing that. But otherwise, everything is mechanically complete. The last puzzle area is still pretty rough in its assets, but it all feels pretty solid. Lots of refinement to go with music and generative aspects. At this point, we're just making it good. There's a lot of things that are final. Like, that set of stairs? That's final! I'm not touching that again.

RY: How do you know those stairs are final?

RF: It's a sanity check. Will I do those stairs again? No, I won't? Okay, it's final.

RY: Hmm. I feel like when I get tired of something, that's when my first draft is done.

RF: Not to milk this, but having a kid is a real motivator.

RY: [laughs]

RF: I always design huge projects and don't finish them. But having my wife and daughter remind me to put my work in a box, to put in my 8 or 10 hours of work a day, and know that's all I'm going to get. And our daughter wakes up at 5:30 AM, so I need my sleep. It forces me to make decisions. It's not perfect, but I'm proud of it, and it feels right. I'm aiming for "good enough." I think it'll make people happy.

RY: That can be the box-out quote in this interview: "I'm aiming for good enough."

RF: No, no, I mean good enough for me!

RY: Which is really good.

RF: Like, when I get someone to test the game, they go, "oh that thing was that thing." Maybe they don't notice that you can change the LFO frequency for the entire space -- and the water level rose! -- and the particles over there, did you notice that? No, of course no one notices! Maybe a lot of the "good enough" is going to go unseen.

RY: But it's important that you put it there anyway.

RF: It's there to try to give a reason for everything, to answer the "why" for myself. And if we can't do that, then why are we even making this thing? If you asked me why something is there in the game, and I don't have at least some idea, then that's troubling. Sometimes you're allowed to say, "because I like it," but we also owe it to ourselves and our players to ask "why" often.

RY: I think I agree with you, but a lot of designers would say that's overthinking it.

RF: It doesn't have to be profound. It can be a trivial thing -- why is that pink? -- which can make you realize that, oh, it should actually be purple? And to borrow an expression from Droqen, that's not to say our game is "whyproof." It isn't.

RY: Now, you said this was your "first real game." What were you doing before?

RF: I had been doing graphic design and art direction for web for many years. I had always wanted to make games, but it just didn't seem practical when there were so many graphic design jobs. I love graphic design. I worked at a big firm, and then a smaller boutique firm, where we'd work with education and museums. On the grand scale of moral value in advertising, this was the good stuff. There, I liked building these interactive tools and systems. I was always picking apart games. Eventually, my girlfriend (now wife) said, "why don't you just make some fucking video games?" And it was a good time for me to leave that career. I did a 1 year "game design" certificate at the University of Montreal. That galvanized a lot of things for me.

RY: What was that program like?

RF: Unfortunately that year, there were a lot of strikes, so the curriculum was pretty heavily disrupted, but that gave me time to work on the original FRACT demo. Otherwise, we did a little bit of everything. We prototyped table-top stuff, also analyzed games in the French film analysis tradition, along with a little bit of technical and a bit of business. There were a lot of people with different backgrounds. Some people from early childhood development, advertising... a small but interesting class.

RY: Oh, I like your "Incredible Machine" on your site. Good choice of materials here, using pinboard was smart.

RF: [excitedly shouting] YEAH! THAT WAS MY IDEA!

RY: [laughs]

RF: ... Uh, it was a team effort. It was definitely a team effort. But I'm proud of that project. And when we put it in front of those kids, it became a hundred times more awesome. The task was to design something with "emergence." That's a buzzword, but I think we did that. It's a sandbox, to give users a set of...

RY: Parameters?

RF: Parameters. Restrictions? You give them enough of a box that they aren't overwhelmed. A blank slate can be too much. But with a scoring system and some objectives, the kids really went nuts.

Plus, I really like making physical things with my hands. My entire career has been digital, but me and my wife are very crafty. Woodworking, leather... there's just so much that can be achieved in the real world. There's something so great about building a tangible thing. I used to work in print, and print was a fucking headache. I hated it. But what was awesome was when it was done, a thing I can hold, a billboard I can point to my mom -- hey mom, I traced that cow!

RY: Yeah, physical work is great. In my own game design education, I made a board game about open pit mining -- a box with dirt in it, and you dig in the dirt. But in-class, no one wanted to touch the dirt to play it. That's something a video game will never do.

RF: Speaking of a box of dirt: today was the first day our daughter played with sand. And I was like, "woah."

RY: Did she do anything surprising with the sand?

RF: She was... overwhelmed. So I had to show her a few things: you can take it in your hand, you can dump it on the ground, you can put a rock in it, etc.

RY: A sand tutorial.

RF: Yeah. Her mind was blown, the whole time. Sand is so simple, but I can't do that in a video game or simulation? It made me think of... oh, what was Eric Chahi's last game?

RY: From Dust? It was the only sandbox game that was actually about sand. Sand is really complicated, the more I think about it now.

RF: It is! In the sandbox, I was making this little pile of sand -- and that, there, demonstrates the angle of repose. Physics, right there!

RY: I'm sure your daughter was impressed.

Another thing that struck me about that Incredible Machine project -- in the trailer, you were really careful to record all the sounds of the ball rolling, hitting things, bouncing off pieces. I never thought of "sound design" as an aspect of board game design before. Here, it's very conscious -- like that great sound when it falls into the cup.

RF: We were pretty conscious of the sounds it would make -- the sounds the ball makes when it hits metal, or yeah, that cup. We used a cup with a sort of cone shape, in hopes that the ball would spiral down and make that spiraling sound. Some of it was more a side effect of the surfaces, of the kids launching lots of balls sliding around everywhere, the kids screaming...

RY: Kids these days! I see them playing with iPhones and feel old. When I was their age, I was playing with rubber bands. They should be playing with rubber bands like in your game!

RF: I'd agree. A lot of my childhood was improvisational, I guess my parents were sort of like hippies. A lot of it was playing with found materials. I think there's so much to be found in that. The magic of banging two pieces of wood together!

My nephews play a lot of video games, they're super smart kids. Last Christmas, I found a re-issue of my favorite book on paper plane design, written by two PhDs in Aerospace Engineering. My nephew and I made a few planes -- and then that was all he did for weeks. From that, he understood the fundamentals of aerodynamics, and developed a more expansive understanding of how to modify the other plane designs. There's so much fun to be had, far away from screens...

RY: Away from a screen, play is usually much more unstructured. Then when you play with the screen, you just want to obey the screen, to be told what to do.

RF: It's not all bad! I think Pinball Construction Set inspired me a lot. It's really old VGA graphics with horrible physics, and you could design pinball games. But when I was 5 or 6, I would use it to design Rube Goldberg machines. I think kids are doing it with "The Minecraft" -- "THE Minecraft!" listen to me, Old Man Flanagan...

RY: You're probably going to have to play Minecraft with your daughter.

RF: I like the idea of Minecraft projects with my daughter. We'll have our sand simulations.

RY: Maybe FRACT could be the Minecraft of sound games, to teach music by building music.

RF: It was originally going to be episodic. There was going to be a synthesizer episode (OSC), a drum machine episode, a turntable episode, a sampler episode -- and each one would contain systems to relate to that aspect of electronic music. But OSC turned out to be more than enough game, so we've comfortably shelved that idea indefinitely, unless FRACT becomes a runaway success? If so, I've got a GDD (General Design Document) this fucking thick [makes thickness finger motions] for the drum machine episode if it comes to it.

RY: You wrote a GDD? That's pretty rare in the indie world.

RF: That maybe came from the academic game design we did, we wrote a lot of GDDs. It seemed like the "real" or "legit" thing to do. It was useful when we approached Indie Fund too -- they read the GDD because the game wasn't exactly complete yet.

RY: For the skeptics -- what's the value of writing a GDD, to you?

RF: Reference. Externalization! Having it outside of your head is so valuable. I'm sure you're the same way -- you have so many ideas in your head that they start to compete. Unless you're special, and you can remember everything you've ever thought of... forget about organization, about communicating your idea. It's about getting it somewhere out of your head.

RY: I think games are getting increasingly polarized about audio. A lot of mobile games, you can play with one hand, no headphones, on mute. We're also seeing games treat audio like the most important thing ever, as if playing with no audio would be pointless. Games like FRACT, or maybe Robin Arnott's Soundself?

RF: If the game is designed to accomodate those short play sessions, the audio should too. Did Adam Atomic's Capsule end up on mobile? I could see it really working on mobile. Robin Arnott did the audio on that too, right? It has such epic sound design. It works very well in these less-than-2 minute sessions. Also, Super Hexagon sounds amazing. It feels good, the music is awesome, and Jenn Frank's voice over -- she *is* the game, to me. It's already an amazing game, but her voice took it to the next level. It works in these micro play sessions with the aggressive music, so I always reached for headphones when I played. Those are both games that require a lot of attention, though. I can't think of anything more passive that pulls it off.

RY: Super Hexagon is great, it's almost like you're dancing. But your movement doesn't match the rhythm, it's more about matching the spirit of it. In sound design (I did research!) they have a term, "mickey-mousing", when on-screen action corresponds directly to the soundtrack -- and film sound people look down on it a lot, for its total lack of subtlety. I think we mickey-mouse in games most of the time, game sound is usually so literal like that.

RF: A game is an interface. Everything is part of that interface. Developers usually say, "here's the mechanic, here's the system, here's the loop." But sound and UI shouldn't be after-thoughts, left until the end! They're the two most crucial things! If the sound is broken, then your game is broken! And I think when sound design is amazing, it disappears. When it is more than just some sauce on top, when it is contextually relevant to the game -- that's what excites me. Why is the UI just a menu with checkboxes? Why does the button roll-over sound like that? Should it behave like that? I'm not confident that we're nailing all this in FRACT, but I think we're at least scratching at it and poking at it.

RY: Until it's "good enough", right? But games mickey-mouse for a reason: you have to be super literal, you have to give 5 different kinds of feedback to the player. In contrast, there's like no in-game text in FRACT.

RF: We have a little bit of text. I'd love to have completely no text, but...

RY: You don't have anything like, "Press F to activate _____" though?

RF: No.

RY: I appreciate how hard it is to develop, especially since you're trying to teach something without just presenting a textbook.

RF: Well, breadcrumbing and mickey-mousing work when you want to communicate something in a hurry. It reminds me of design in advertising and web, how we made things for people as if they were complete idiots. (That's being diplomatic, compared to the words we used.) We measured attention spans in seconds. I think gamers have a much longer attention span, and are much more emotionally invested in things. They paid money for it! So, I'm going for "alien", but decipherable.

But I see FRACT more as a primer, a musical toy. Before, I was having a huge crisis of confidence in what we were trying to achieve. I felt like we weren't I wasn't teaching players how an ADSR envelope was working on a filter versus an amplitude circuit? "We are simulating a synthesizer, with extreme precision! We have to teach them how to use it, with extreme precision!" How do I even explain that in words to someone who didn't know what a synthesizer was? I was devastated.

But I realized the value in music was just in letting someone make sound. Hand my daughter a drum and she's satisfied with banging on the drum. Turning a knob on a synth is satisfying. I'd love for it to be a primer, if someone spends 5 minutes or an hour in the studio in FRACT, that's great, and hopefully they'll walk into a music store later.

RY: What if you're tone-deaf? What if you just don't understand music at all?

RF: If you're tone-deaf, no problem. The audio puzzles should not be too difficult. If you can't hold a beat to save your life, or if you have no rhythm, you'll be just fine. And you know what? The music you make will still sound pretty cool. We've put a few restrictions on the tools so that they produce some nice things.

RY: Oh, like what restrictions?

RF: We have a series of "primary chords" for some areas of the game. They're friendly. Some puzzles are more flexible than others, and might let you put together something more sinister, but other sections of the game are more curated. But the beginning is definitely more reined-in, at first.

RY: It reminds me a little bit of the sound design in Starseed Pilgrim.

RF: [embarrassed] I... I haven't played Starseed Pilgrim yet.

RY: What?

RF: I know, I know, and everyone's telling me it's my type of game...

RY: Michael Brough wrote about this, he argued that "spoiling" Starseed Pilgrim isn't really spoiling it, that we should give the game more credit. FRACT is about exploration too, do you think FRACT is like that?

RF: There are definitely some aspects of FRACT that are spoilable. But at the same time, I don't think this is a hard game. Some of the hardest puzzles are actually at the beginning of a section, because they're more rigid, but it's not that necessary to enjoy the game. I do think it'll enrich players' understanding if they can decipher it, if they can go [adopts higher-pitched whimsical voice, points around room], "Oh, that's that! And that's that!"

RY: So, what are we adding to the first person game?

RF: "What are we adding?" That's it? There's no analysis?

RY: Oh, okay. Analyze it.

RF: Emotionally, it feels kind of sad, with how limited you can move in the beginning, like a loss of control. Once I came to terms with pushing and pulling to get somewhere, I felt like it was breaking a wall. Naturally, I felt there must be a "why" here. That reinforced the question, who / what am I? That propelled me to keep playing. Once I hit the water, and gained more control, I realized that this is where I (or my character) is more comfortable, this is where I'm meant to be.

Let me restart the game, to confirm something... [plays] Hmm, I can't turn around and go backwards. I wanted to know why.

RY: Do you want the technical reason?

RF: [laughs] Sure.

RY: It's because the entire world is shaped like a shallow funnel, and the walking speed is so low that you can't fight gravity, up this gentle slope. That's what I'm guessing is happening. Why, do you want to add something in the back?

RF: I wondered if I was the guy who looked back, the guy who turned around and wondered what was behind those two rocks. Maybe something subtle, a light cue. But how would you get there? Maybe with the slow-ass walk, to be extra punitive...

RY: We can put extra poles to pull yourself with, hidden behind a rock, and you wouldn't see the pole until you take a few steps past the rock.

RF: That works. Right behind the two rocks, directly behind the player at the start. It looked like an opening, a clearing. I wanted to see what was there.

RY: What do you want to put there? Right now, there's nothing, it's just a fake tree silhouette card to fake the complexity of a forest.

RF: I'm really hesitant to make drastic changes. I don't feel comfortable. I know I have pretty hardcore imposter syndrome, that's a big factor in this. Also, I know you personally, so I don't want to send you off on a crazy mission. There's a weird courtesy to it.

It reminds me of an exercise in art school, introductory drawing class, where the professor would setup a still life for someone to draw, but everyone else can only see the next student's easel but not the object. So you make conscious choices about how you draw, to help out the next person to figure out what it is, and copy the shape and form. I went to a super hippie art school.

RY: Those are the best kinds, I think.

RF: The design program had no computers. Partly because they were poor, partly because they were anti-computer.

RY: Are you thankful for that? No computers?

RF: I already taught myself Photoshop as a kid. Tools become obsolete very fast, so I wanted to learn "how" and "why" instead of tools. I had buddies who went to school to learn Flash!

Okay, so because it's on my mind: let's add some sort of body of light, an area that has a glow. And when you're standing in that area, there's a subtle sound that's a combination of the wind and a subtle (but pleasant) whisper. Like a subtle choral?

RY: A choral note, as in, like, [angelically] "ahhhhhhhhhh" -- like that?

RF: Yes. It sound super cliched now... Ah, whatever. Whatever! And when you stand there, you hear that. But it'd be a pretty subtle roll-off. Is that too much?

RY: That'll take me like 20 minutes at the very most. Maybe more.

RF: So you keep pulling on these poles, slogging back, to a certain zone. And once you're there, you can see something large in the distance. Whether it's a radio tower, or -- oh, like Dear Esther?

RY: How big is the clearing?

RF: I was picturing half an acre, like pretty big for flowers to grow...

RY: As big as the main lake area?

RF: Smaller. Maybe a third of that.

RY: Hmm. Do you see only the shape of the tower? Are there any lights on it?

RF: It should be clearly manmade, but maybe not obviously a radio tower. There's a light, but the frequency is far apart. It's possible for the player to miss it. Maybe every 15 seconds, it blinks. And the color of the light... let's get fancy... is pink.

RY: Are you picking which pink?

RF: 255, 19, 79.

RY: Great. Is there only one light on the tower, right at the top?

RF: Yes. In terms of feel, I want the player to think -- "oh, did that just happen?"

RY: ... and then it never happens again, and you're not even sure if it happened?

RF: Can you do that? Can you make it so that it only happens when the player is looking at it, and then never again?

RY: Yeah.

RF: This all comes from a memory I have from when I was a kid. I remember it was right after the big ice storm in the 90s, it ravaged all the trees... but I remember I went for a walk with my cousin with these crampons, these shoes that let us walk on the ice. But because there were no trees, there was a lot more light coming through the trees than there ever had been. The light was refracting off the ice.

And then we saw the radio tower -- 10 or 15 miles away -- but in all those years of living around those woods, I had never seen them before. There was a moment when we were like, "what is that?" And we were kids, so we thought someone was signaling us? So we were walked in the moonlight, with everything covered in ice, and of course we realized this thing was a radio tower.

But still, there was a moment when we wondered: what was this thing, what was this excitement?

RY: Thanks for your time.

This transcript was edited for clarity and length.