Zenomorph: The Art And Evolution Of Zeno Clash

The Zenozoik Era

This is the first in a weekly series of features about the art and art technology of PC games, in association with website Dead End Thrills. More from Zeno Clash II can be found here. Click the images below for biggies.

Punch me in my Salvador Dali and tell me I'm not dreaming. Did just fifteen people really make Zeno Clash II? Of course they did, it's by ACE Team, the Chilean house of brothers Andrés, Carlos and Edmundo Bordeu. Making a game that actually seemed possible would be too easy for those guys, and maybe even lose the underdog cachet that makes their first-person brawlers so disarming.

Zeno Clash - or, as I like to call it, Hieronymus BOSH! - was conceived in 2002 as a prototype first-person adventure called Zenozoik: Shattered Land. It was, Carlos almost proudly declares, "really bad. It was a mix of several ideas that were too ambitious for a small studio at the time. Even saying we were a studio would be a stretch, we were just a bunch of dudes."

Amusingly, one of these ideas was pacifism. NPCs would respond in kind to how you played, making it possible to just charm your way to the end. Again, "it worked awfully. Getting NPCs to interact with you, and understand whether you’re being aggressive towards them, that’s really hard. And it’s even harder if you’re in this punk fantasy world where everything looks menacing." Non-violent quest options made the game exponentially more fragile, and testers used to Counter-Strike were just shooting the place up anyway.

So, in the production version of Zeno Clash released in 2009, NPCs understand more quickly whether you're being aggressive to them. It's the mandatory punch in the face that does it, then the highly recommended soccer kick to the face, and then the in-for-a-penny stamping on the face. They tend to get the message after you've done that a couple of times.

The switch to Rock 'Em Sock 'Em brawler earned the game cult status, but not for the reasons you might think. Bringing to mind The Chronicles Of Riddick: Escape From Butcher Bay, this kind of screen-consuming melee system can make stars of a game's characters, lending unusually high resources to their texturing, animation and expressions. Inspired by the likes of Bosch, British fantasy illustrator John Blanche, and Python legend Terry Gilliam, Zeno Clash was quite shamelessly now an 'art game'. With fighting.

ACE Team had clearly learned from its mistakes, even if the next one always seems to be just around the corner. "If you want to do a game, you do what your engine does best," says Carlos. "We don't! ‘What does this engine not do? Let’s do it!’ That doesn’t make a lot of sense but it was at least the case for Zeno Clash."

It was also the case for pretty much everything else the studio had done. You know how in Doom you can't have one floor above another? "We sort of did that in Batman Doom [a mod that pretty much explains itself] by doing some really creative sort of hacks. It was an illusion, almost cheating," he recalls.

Zeno Clash was in fact supposed to be a Doom 3 engine game before the team, recognising its problems with exteriors, chose Source instead. Much has been written about how it then proceeded to totally eschew Source's brush-based geometry and bake all its lighting into static meshes in 3D Studio Max, all for the sake of a more organic-looking game world. Which worked, of course, in the end, but not as a foundation for this year's Zeno Clash II.

Switching to Unreal Engine 3 for a bigger, more open sequel, ACE Team played it unsafe yet again by designing over 100 unique characters, more than trebling the size of the game world, creating one of the first and only simulated day/night cycles in Unreal, and telling a bigger story complete with voiceovers and cutscenes. This time the fight was with workflow rather than technology. As Carlos puts it, "Now we were hacking ourselves."

Though one of the most bewitching UE3 implementations ever, full of chemistry and colour, Zeno Clash II isn't perfect. Mistakes were made which, all things considered, seem almost ordinary.

"It was quite a successful project and a very worthwhile sequel," believes Carlos. "We did a lot of stuff to really address what people were asking us to do. On the other side, I do feel that the game is maybe more for hardcore Zeno Clash fans, and I don’t know what I could have done to not be in that situation. The first game ended with a cliffhanger, in the middle of something you really needed to follow up. A lot of people who went into Zeno Clash II didn’t really get it. I was disappointed that many people talked about the story being just this weird thing without any purpose, whereas it was thought out really well. It’s our fault.

"A concrete example is that we left the tutorial and prologue out of the main campaign so, if people were in the middle of the campaign and forgot how to do a combo, they could go back and re-practice. The problem is that if you go and see people doing their first impressions on YouTube, they skip the tutorial and everything, and it’s a disaster. I want to pull my hair off, kill myself. So yeah, maybe that wasn’t the best idea in the world."

There's little question that Zeno Clash II is overambitious, "just ACE Team trying to do something you’re not supposed to do," says Carlos. "It’s not the engine this time around but you’re not supposed to make something that’s a big adventure with multiplayer, with co-op, for PC and console."

Its art, however, though an acquired taste, is a feast. From the convincing mix of baked ambient occlusion and dynamic lighting, to the ridiculously broad palette of moods and ideas, the game over-delivers by even the triple-A standards the team cautiously plays down. Time to get on the tour bus, friends, with art director Edmundo Bordeu.

Bosch Spice

Yup, that title did just happen. The influence of Dutch surrealist Hieronymus Bosch on Zenozoik is not just some early aspiration seized upon by ACE Team's marketing. (Does it have marketing?) Nor is it always so explicit as the turning of the 'Tree Man' from Bosch's Garden Of Earthly Delights into a roving 'cavity on legs' that poops out bombs, has glass bubbles for kneecaps, and serves as a half-time boss battle.

Layered parallel planes littered with unique props and characters form many, if not most, of Zenozoik's landscapes - and this is a very realtime phenomenon. But for all the time and resources games spend trying to plug those gaps, achieving a kind of spatial 'realism', ACE Team spends just as much going the other way.

Edmundo: "The Bosch reference is very difficult to achieve because each square inch of a Bosch painting is unique. Every single creature is different, every single prop. So, making Zeno Clash II bigger than Zeno Clash 1, one of our main worries was how we were going to fill this huge space with different things. You can't make every single square inch unique, so you draw people's attention to the things that are unique.

From a designer point of view, we decided that if there was something really interesting in the background, like say this gigantic egg sculpture or the tower, you had to be able to reach it. So we couldn't put something in the distance that was cool-looking but oh, you couldn't go there. That's why you have these kind of 'set-pieces' that are very evident in the background.

Proportion is certainly easier in a fantasy game. You can say that something's important and make it twice as big, whereas in a realistic game, if a phone is important then you can't make the phone twice as big - that'd be ridiculous. I wouldn't be surprised if some of the landmarks [in Zeno Clash II] were reduced or enlarged to four times their original planned size. So yes, you want the gameplay to be readable, and again you want to draw attention to things that are special in these huge spaces."

Father-Mother Of Invention

Edmundo's approach to designing characters is, unsurprisingly, the opposite of what you'd expect. Others might want to know every detail of a character's attitude and history before calculating their appearance, but the characters here come out backwards.

Edmundo: "Not all the designs come from the same person [on the team] or the same few sources of inspiration. Once we have a lot of designs out there, then we decide where they fit in the world and the story. If we have someone with a classical-inspired design, for example, we say he fits more in the Golems' world. Even the backstory of a character doesn't exist until we can see him on paper.

Father-Mother wasn't even a secondary character at first, he was a prop. He was sitting in a bar and I thought, 'Oh, this character looks a bit boring,' so I made it that he was a father who'd brought his baby to the bar because he had nowhere else to leave it. The baby was just laying there on the table. All the playtesters who came along and played that level said, 'Ooh, that creepy witch character's going to eat that baby.' I thought that was very unfair, and that reaction to Father-Mother influenced a lot of the conflict in the first game."

The Uncanny Country

In a rare case of ACE Team making life easy for itself, its more batshit characters (read: most of them) bring none of the usual anxieties over realism and the uncanny valley.

Edmundo: "You don't have very particular expectations of how a bird man looks when he frowns. So yes, you can get away with doing things that don't need to match a specific mental model. Still, we had so many more characters in Zeno Clash II than in Zeno Clash that the art team was under huge pressure to release enough. I think our team, for the size it is, to release that game on consoles and PC, did a tremendous amount of work.

In Zeno Clash 1 it was one of our objectives that every person should have a face and a name so that you weren't punching a generic army of clones. Obviously the story requires that sometimes, like with the Desert People or the Shadows, but elsewhere it's always different characters.

Another thing we wanted to do from the beginning: in firstperson shooters you usually shoot characters when they're far away and it doesn't matter how detailed and awesome their face looks; but in Zeno Clash the character is normally using half your screen, so they have to be detailed, they have to have expressions. It's not a tech feature but an essential part of it. Is the guy angry? Cocky? We have a whole emotion layer in there where if the guy's angry he'll attack more and defend less, stuff like that."

Divine Comedy

Terry Gilliam once described his work, so similar to this game's as it can be, as the result of 'conversations' he'd had with other people's art. Sometimes he showed respect, sometimes he took the piss, and somewhere out of that came everything from Brazil to Conrad Pooh's Dancing Teeth. Zeno Clash walks a similar tightrope and, for all its perils and grotesques, never plunges completely into nightmare.

Edmundo: "I read an art analysis about Bosch's paintings. Some people think it is very moralistic and supposed to scare people; of course, art was educational, etc. But other art historians think these scenes weren't supposed to be scary and were playful. Even on Bosch people can't agree if it's serious or just imaginative and funny. In Zeno Clash there's definitely seriousness: the main characters, usually their motivations, aren't comedic in any way.

When I have a very strange or ugly or unusual character, I don't necessarily treat him like he's stupid or laughable. Even if the design is ridiculous, I try and treat the character with respect. With the Golems we were a bit more strict: this is what they were trying to communicate, this whole thing of authority. How they present themselves has to correlate better with their ideas because that's their thing, they try to build the world in their image. But people in the city of Halstedom and the wider Zenozoik have absolutely no prejudice about how strange things are."

The Changing Of The Guardian

Try to contain your surprise, but something strange happens between Zeno Clash and Zeno Clash II: your companion and platonic love interest in the first one, Deadra, is swapped in the sequel for Rimat, an antagonist. Of course, no one is entirely evil in this universe, especially when it's family, but it's still akin to Half-Life 3 swapping Alyx for Dr Breen. "Sorry, Gordon, for being such an idiot back there."

Edmundo: "We had a ton of different designs for Ghat originally; seeing the design that stood out meant we could then define what he was like. Ghat's almost nihilistic in the first game, but in the second one he kind of has his own goals. I read just today, in our forums, he was described as an 'anarchist libertarian'. It's a weird thing to call someone who's never read a book, but that's how he feels he needs to act.

We wanted him asymmetrical from the start. He has these armour pieces that are personal, but not put together carefully. In the second game he's a little less thin because-- This is my view on things, but thin characters I usually relate more to frailty or something missing psychologically.

Rimat was one of my favourite characters in the first one, but the story didn't have much focus on her. Even if it's not in the first game, I always felt that Rimat did know that Father-Mother wasn't her Father-Mother, and that's actually what made her so angry with Ghat: she could keep the secret and swallow the pain just to keep things well in the family, but Ghat was selfish and created this whole conflict. Coincidentally, my sister and other people who played the first one said, 'Oh, I'd like to be Rimat,' more often than Deadra.

We gave Deadra more of her own decisions to make and her own character arc in the second game, whereas in the first one she's asking a lot of questions to Ghat just so he's not monologuing the whole time. In reality, though, almost her only function in the first one is being empathic and the grounding force for Ghat."

Lights and Magic

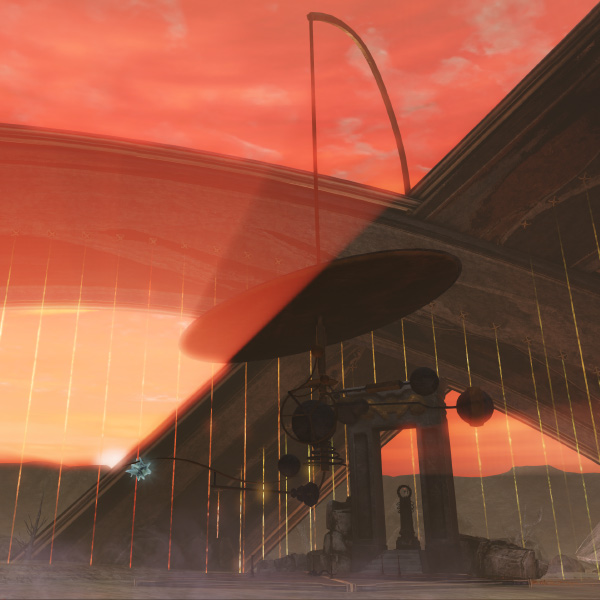

The more apocalyptic the game, the more likely it is that the antagonists will have all the light bulbs. This is beautifully upheld by Zeno Clash II, where the ancient Golems literally electrify a world of mottle and daub, wrapping its stone in holograms and wires. Trespassing onto their island, Ghat and Rimat are quickly surrounded by marble ramparts and enchanted jewels, not to mention tall obsidian watchmen, the Shadows, whose movements seem based on gaming's creepiest glitches.

Edmundo: "The second game definitely has more focus on the Golems because in this one we're explaining more what they are, and a lot of the conflict is between the Golems themselves. Electricity, and these cyan, green and blue lights, are what we decided would differentiate their advanced technology from the primitive Zenozoik. In the case of the End World [a later level] we really wanted it to not actually be the end of the world, but to let the player see that there's a whole other civilised world beyond it. We knew it was a bit risky to show this cool modern city to people and then tell them no, they cannot go there. But that really makes people hate the Golem, even if the Golem in general are not bad people.

In both games we decided that Golem architecture would be of materials that basically last forever: marble, gold, and these things that, no matter how expensive they are, form kind of monumental, impossible buildings. Gold really doesn't mean much to people in Zenozoik because there's no currency, so in a way they're obsolete symbols for Zenos. And the Shadows, they were supposed to be almost like modern art in a way, because the Golems can decide what shapes they want their minions and even themselves to adopt. They decided their upgrades, they use their own reasons and desires to say, 'Okay, I want to have these symbols of authority, this Greek look," or some other symbol like a crown.

Sunstroke

There's a piece by John Blanche, usefully 'Untitled', that seems awfully close to Zeno Clash II's loading screen. Even more usefully, I can't find it to show you. It's a fairly straightforward image of a sun setting through the layers of smog and grit that choke even Blanche's most idyllic scenes, a web of thin black branches in the foreground. That's basically the loading screen, too, the trick being that its bottom 'layer' rotates with the game's day/night cycle. For the game to be perhaps the only Unreal Engine game to simulate a full shadow-casting sun and moon - I'm really struggling to think of another - is one thing. But what's magical is the art of it, how it mixes with layers of atmospheric detail to create roiling, multi-coloured skies.

Edmundo: "It took a lot of iterations. The main difference between trying to do a simulation cycle and what we did is mostly choice of colours - like, say, the sky light can be pink and the backlight can be green, and the fog can be something that doesn't clash with those. Second is the skybox itself, the image. Those two things find the right balance between how real it needs to look. Because if it's completely abstract, that will clash with the rendered scene with its shadows and aspects that are real in a way. Surrealism is not necessarily a Picasso painting where nothing has to make any sense. It has a dreamy quality to what it is rather than how it's drawn.

One trick we have is that when the sun is very close to the horizon, when the shadows would be most bothersome, the intensity of the shadows fades and it turns almost 100 per cent into ambient light, which is not directional. And then during the night the moon illuminates things. My favourite time is right before this horizon time, when the shadows are very horizontal, where the sun is intensely red and you have these long shadows. That's my favourite time in real life too."

Texture Clash

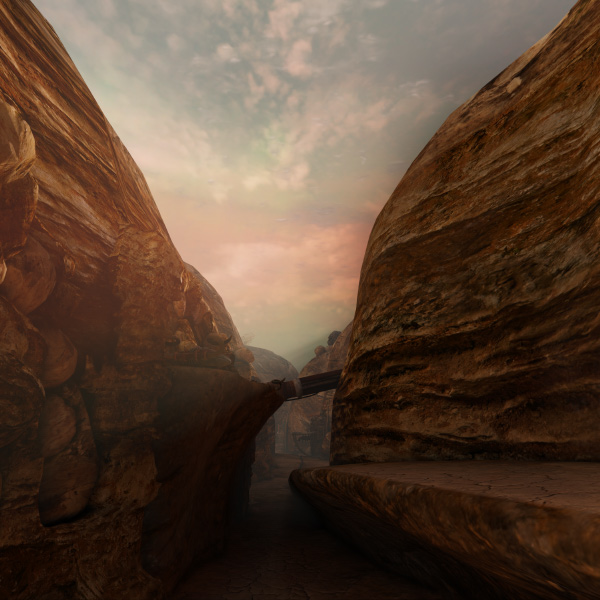

Trust Zeno Clash to not conform to any one current model of 3D texturing and colour-grading. It doesn't use the compression-friendly painterly style of Dishonored or Brothers: A Tale Of Two Sons - at least not always. It doesn't always try to hide the photographic origins of, say, its rock textures, or use a sepia wash to achieve a unified look or conform to expectation.

Edmundo: "I don't think it's usually difficulty in making things look real that makes people lower the saturation and things like that, but a conscious decision. Saving Private Ryan, for example: after that movie, so many war games used it. It's how people expect these games to look, like how a sci-fi game should have these blue hues... When we said we didn't want to do this in Zeno Clash, it wasn't because we wanted ours to look better, but because we were bored of these styles. We want to make something look different, even if we cannot achieve the most beautiful look and it looks ugly.

We do use photographic reference but we always process it in Photoshop, trying to keep a consistency between the things that are pure fantasy and photographic, finding an area in between. We did do some attempts at using post-processing to kind of have these styles you could get away with, but we found out that usually people prefer to look at it without the post processing on. Now I have learned more about post processing and so we might use that for the new project. But Zeno Clash has a very thin layer."

Region Coded

As good as games now are at using skyboxes to communicate distance and place - a Citadel here, a Shard there; a Founders Tower or abandoned radio mast - few attempt more than the hub-and-spoke tactic of having one key landmark that reminds you that you're 'there'. Zeno Clash II prefers a kind of camera obscura approach that maps most of Zenozoik onto the skydome, the obvious risk being that the whole place feels like a theme park.

Edmundo: "Before creating the levels I first created a world map where every region would go. I even created it in 3D, and for a very long time in the project each level was placed in its exact location on the planet; one level would be 1,000 miles north, etc. We even had technical difficulties because in the engine you're not supposed to do things so far away from the origin of the level. But it helped us keep places where they actually had to be in relation to each other.

For the final game we realised that the distances I'd picked were way too realistic, and so great that you couldn't see the landmarks far away. So, though I was afraid that making things bigger and closer to each other would make the world of Zenozoik look too small, it was better for the final game.

We had this thing where my map actually represented part of Chile. In the first game, just without thinking it, we put mountains on one side, sea on the other and a desert to the north. And I realised that of course we did that, that's how the world is in Chile. So we worked that in, made it explicit if you search the lore in the second game. Of course, the distances you travel in the game are ridiculously short, but when did they ever have to be realistic?"

You can follow ACE Team and Dead End Thrills on Twitter. There was a better prize for getting to the end, but I ate it.