Letters From Nowhere: Silent Hills

South Vale Tales

Dear RPS,

There's a place that I sometimes go to but I rarely talk about it. I can't find the words. Maybe the only way to tell you is to go back there and to write everything down in a letter. So here I am. The first time I came to this place, this special place, I didn't have the courage to remain there alone...

It's easy to forget that Silent Hill 2 is available on PC, if you ever knew to begin with. With no digital download available through legal channels, the physical copies available are usually being flogged on the Amazon Marketplace or ebay for £40+. There's an occasional cheaper sale, usually unboxed, but the third game is far easier to find at a decent price, and the fifth title in the main series, Silent Hill: Homecoming, is available on Steam.

Unfortunately, neither homecoming or Silent Hill 3 are likely to convince a newcomer to the series that it deserves its lofty place in the horror pantheon. The third game starts well, fracturing an ordinary day at a shopping mall to leave fragments and splinters that burrow and squirm under the skin. However, rather than being a character-driven psychodrama, like Silent Hill 2, or a work of weird fiction, Silent Hill 3 is restricted in its storytelling by the mythology of the series.

It is, in part, a direct sequel and concluding part to the story of the first game, although it does feature a new protagonist and passages of play that are self-contained viginettes as unnerving as could be desired. The reliance on loose threads from the original and an eventual reversion to the muddled and mystical mean that it's not the best place to start.

As for Homecoming, it's the equivalent of a direct to DVD release at the tail-end of a once venerated series. It came into the world from the creative womb of a new development team (Double Helix), and a marketing push that emphasised the new combat system. The previous games admittedly had combat that could generously be described as thematically appropriate in its awkwardness, but it's never a particularly good sign when a survival horror game falls back on fighting rather than frightening.

I think of Homecoming, along with Downpour (another numberless title), as an interlude from the core of the series. But, as I look through the list of releases, I realise that it's Silent Hill 2 that is the real interlude. Along with the excellent Shattered Memories, the second game is far superior to its silent siblings. The first game deserves mention and credit for introducing the titular town and the initial interpretation of it, as well as the beginnings of the psychological shocks and peeling back of the psyche. It also contains the first threads of The Order and cult mythology, however, that become a crutch for the series' more familiar horror waffling.

Silent Hill 2 has little in common with its predecessor. As the thirteenth anniversary of its release approaches (on Wednesday), it is still the greatest horror game I've ever played. With that anniversary approaching and the announcement of Silent Hills for the Playstation 4, I decided to revisit the town in the company of the great pretender James Sunderland on a summer weekend, and found new things to love. Without spoilers, this is Silent Hill 2 and what it means to me.

Well, I'm alone there now...

In our 'special place'...

Waiting for you...

Ghost Story

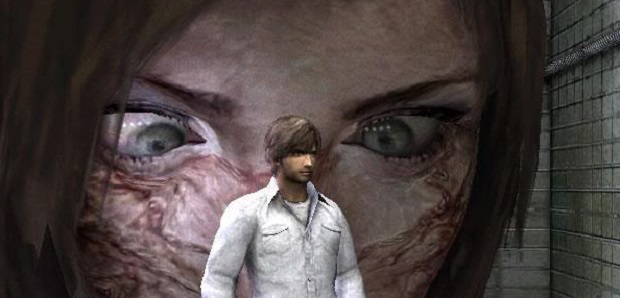

James Sunderland receives a letter from his wife, three years after her death. The letter brings him to Silent Hill, which is a ghost town in a literal and literary sense. Seemingly abandoned and fog-shrouded, it has the qualities of a Mary Celeste, and it would be no surprise to find a great body of water at its boundary, isolating it from the rest of the world. It is a place adrift.

Water is an important motif in the game and when James eventually casts off onto the lake, which is a central element in his own story and the town's history, it has the qualities of a threshold. The sense of being at the border of reality, of scratching and bruising the liminal, is a vital element of the game's setting and mood.

James arrives at the town via a secluded walkway, a journey that lasts just a little too long for comfort. It's a distancing effect, marking the transition from one kind of reality to another, but it's also a clear denial of genre conventions. No monsters, no puzzles, just a linear path, a walk, a conference of whispers and footsteps.

The tone is perfectly set. At times it sounds as if James is being followed but nothing manifests and if you choose to stand still, as soon as the sound of your footsteps ceases, so does the sound of whatever might be lurking in the undergrowth. The camera angles are indicative of eyes in the fog, things waiting and watching. They don't pounce though and they don't make themselves known.

Nothing terrible happens as James approaches the town. A meeting in a graveyard is confusing rather than horrific, and the final stretch of the journey is marked by the banality of chainlink fences and an industrial hinterland. No traps, no jump scares, no sense of an ending.

And so I wait...

Industrial Nightmares

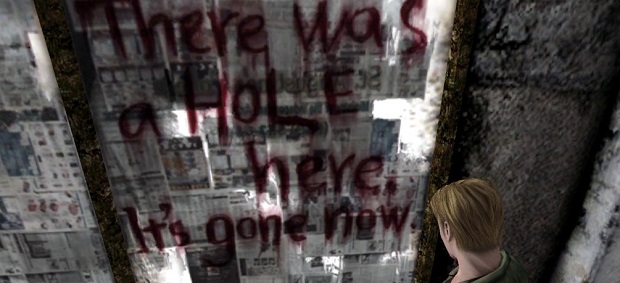

Nothing happens but everything is possible. Silent Hill shows its monsters eventually, but it creates spaces for the imagination to fill during that first long walk into town. Silent Hill, as both a game and a place, has mechanical and industrial qualities. Although it rarely reaches through the fourth wall directly, it isn't averse to displaying and alluding to the cogs and gears that drive the apparatus of the ghost train and the haunted house.

In Philip K Dick's fragmented nightmare, Ubik, Joe Chip holds onto remnants of reality by deferring to the logic of machines - "Machines could not imagine." Despite its humanity, Silent Hill 2 is a game that understands the threat of machines as well as flesh. Many of the most uncomfortable scenes contain human-like constructs - Frankenstein's mannequins - and the sound of metal blade scraping on metal bone. There are tears, blood and at least the suggestion of almost every other bodily fluid as well, but many of James' ghosts are in and of the machine.

Like so much horror, Silent Hill 2 is about the failure of things - of nerve, of compassion, of organs, of machinery, and of mind and body as a whole. Everything is in a process of decay, a town that has aged decades overnight and still carries traces of lives continuing just around the next corner or through the next door. It's unclear if James himself is the ghost, walking through lives in process but failing to see them through the shadows of his own state.

It’s not that I'm getting better.

Body Horror

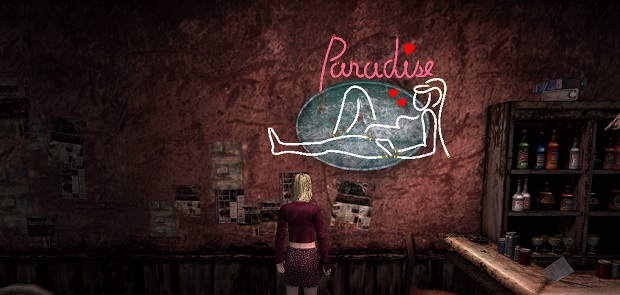

Silent Hill 2's monsters are manifestations of its mysteries. Later entries in the series have been rightly criticised for recycling iconic creatures until they become mascots rather than meaningful entities. The unnecessary reuse of the creature known as Pyramid Head is most often the target of criticism, but I find the regular appearance of the nurses even more bizarre. They often appear out of context and have smoothly transitioned from being a psychosexual horror fantasy, product of a stunted and quasi-Freudian erotic urge, specific to a single character, into pin-ups. That's not just a symptom of the film adaptations and fan art - it's evident in some of the later games as well. Everything in Sunderland's story is precise and there is a cohesion to the cast of malformed creatures, but the same is not true across the series.

The first living (?) things seen on the streets look like straitjacketed patients shambling in the fog, but typifying them as such is evidence of a reliance on the expected tropes of horror. Madness visualised as a dangerous, restrained lunatic, a gurgling, bloody carcass animated by cartoon psychopathy.

Horror often relies on an injection of the unfamiliar into the familiar, but so much that was once unusual and uncanny has become familiar through repeated use in fiction that the box of tricks is depleted. There are several approaches to take, two of which are superbly demonstrated by recent films. The remake of The Evil Dead stuck with a familiar formula and ratcheted up the gore and body horror - it may be broke, but turning up the volume is easier than fixing it. Cabin in the Woods played with many of the same cliches and warped them into a running commentary on the genre, shot through with black humour.

Silent Hill 2 hews closer to Cabin in the Woods but it's approach doesn't even have a hint of a smile, let alone a nod and a wink. Part of the game's genius is in its representation of the supposedly unexpected trappings of horror at face value, and then a slow disintegration of those same effects, leaving something far more uncomfortable and unnerving among the remains.

In this game, madness isn't a violent force, nor is it loud and angry. Silent Hill 2's psychology is that of grief, hope and loss rather than a mostly invented animalistic fury. The edges of sanity are malleable, recognisable and human. Sunderland's doubts and fears are capable of infiltrating and residing under our skin because they are the residue of something already there.

In my restless dreams,

I hear that town.

The Sound of Silence

Whatever failings the series may have accrued over time, Akira Yamaoka's work as sound designer and composer has rarely stumbled. I can recognise almost every room and location in the games by hearing the sounds associated with them. There are places that I have to leave after a minute because the looping, grinding chips away at my own internal health bar.

When I think of audio design in games, I tend to think of Thief's brilliant mechanical use of sources and interactive sound. Yamaoka takes a different route, composing a jarring symphony that doesn't affect the avatar or the state of play, but cuts directly into the player. Sometimes it's an assault and sometimes it's a lingering sense of dread. Every now and again, there's a song from the hit parade of another world.

...laying here...

Tragedy

Even though it's certainly the most intensely frightening game I've ever played, my reaction to it has changed over the years. It reminds me of A Tale of Two Sisters, a film that can make my blood run cold even just through remembering its most harrowing scenes. But it's not a horror film, not really. It's frightening but its narrative is tragic and as I watch it again, I brace myself at certain moments but am more likely to cry than to cower.

Silent Hill 2 is the same. I still can't play certain sections without company - I am the world's most cowardly horror fan - but the lasting sense is of sadness rather than spooks. Tragedy requires flaws and the game's narrative of decay is built upon human failings of every kind. It's a more sorrowful experience than a stack of melancholy 'art games'.

You promised me you'd take me

there again someday.

But you never did.

Silent Hills

If you haven't played Silent Hill 2 and have any interest in horror, you must. Indeed, I'd recommend the game to people who simply have an interest in the evolution of the medium, whether they enjoy horror or not. Chances are you won't actually enjoy it at all, whether your in the mood for terror or not. It's not a game to be enjoyed, but then neither is Bergman's Persona - some work is intended to disarm and dismantle its audience.

The HD release of the trilogy on console is poorly remastered but might be the cheapest and most readily available option, but if you can find the original on PC, it's the definitive version. Not many people realise that - the series is at home on PlayStation but its best entry found a home here, on the computer.

And I have hope that Silent Hills, which was announced by way of a playable teaser a few weeks ago, will come to PC. That initial concept demo and a new trailer are reminiscent of the fourth game, The Room, which had peaks as high as anything else in the series.

The cynic in me recognises a terrifying take on the walking simulator, which is nothing new or particularly inticing, but there's a sense of otherness that is still unusual. The ending of the trailer, below, holds the horrible promise of all of the elements above. Hauntings, tragedy, industrial noise and humanity stretched and distorted. Whether there will be meaning behind the monstrous again is yet to be seen, but I'm eager to find out.

If we can have Metal Gear Solid V, perhaps we can have Silent Hills as well. It'd be so good to go home again.

Well, this letter has gone on

too long, so I'll say goodbye.

This article was originally published as part of, and thanks to, the RPS Supporter program.