Fantastic Cartography: Why Videogame Maps Matter

From The Archive

Every Sunday, we reach deep into Rock, Paper, Shotgun's 141-year history to pull out one of the best moments from the archive. This week, Adam's celebration of videogame cartography, from cloth maps to digital records of procedural worlds. This article was first published in 2011.

Some of my earliest memories of gaming are not of the games themselves but of the things that came bundled in the box with them. Whether it was a hefty manual, full of lore and encyclopaedic listings, or a little extra something. My games don't even come in boxes anymore. Recently, I've been thinking about the shelves in the house where I grew up, full of big cardboard slabs with none of this DVD case finery. I've been remembering the excitement of opening the box on the bus, surreptitiously because my parents always thought I'd lose the manual or disks before we reached home. And I've been thinking about what else I sometimes found inside.

When it came to exciting extras, Infocom were the kings. The Lurking Horror was a good one. The player is a student at G.U.E. Tech, which has a great deal in common with Lovecraft’s Miskatonic. Inside the box, my excited boyish eyes discovered a student ID card, a guide to the campus and, horror of horrors, a rubber centipede! It’s easy to mock but it was genuinely exciting, not only because owning things was still quite novel for me back then, but because it was an attempt, no matter how crude, to make imaginary worlds easier to believe in.

There’s one physical object that came to define the area around my computer desk though. Not tiny figurines, as with many of my friends. They’ve never interested me particularly because they have an opposite effect to the Lurking Horror's student ID card. Figurines highlight the imaginary nature of the world. If I am holding a statuette of the player character, no matter how finely crafted, it serves to emphasise that the people of that world are collectible objects in the real world. It places me, as the player and collector, in a different relationship with the game world and it’s an entirely different sort of buzz to owning things that appear to be from that game world.

So, no figurines for me. The items that dominated my childhood gamespace were maps.

If I looked up from my monitor, I could see, pinned to the walls, many of the lands I’d explored, as well as the new ones that were still nothing more than ink on paper, great unknowns populated by who knows what or who. Like a good manual, a good map primed me for the game. I’d wander digital realms and discover locations only to realise, I've read about this. I've seen it. Being able to connect the map on the wall to the city on the screen added a layer of integrity that I felt but didn’t understand at the time. Even when I wasn’t playing the game, I could see the map, over my mum's shoulder as she busied about while I prepared to leave for school in the morning, one last look back to confirm what I knew. Other worlds were always waiting.

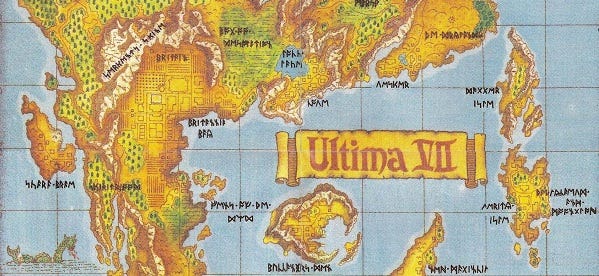

I’ve still never seen a finer collectible than the cloth map from the complete Ultima VII collection. I studied it so much and played that game so long I could probably draw it from memory, and every location, every building and every fork in every road, has a hundred tales associated with it. All my own.

Then there were other kinds of maps. The ones that I drew by hand on countless sheets of notepaper and in school exercise books. I used to play Dungeon Master and Eye of the Beholder with my sister and we’d take turns controlling the action. While one person took control though, the other wasn’t just watching, they were playing as well, pencil in hand, drawing corridors and rooms...annotating. Not only was it a social experience, it added another level to the game. We were essentially roleplaying those characters, one the leader, another the scribe. There were no cutscenes to show it, but we knew they huddled around a campfire whenever they rested and took out the parchment to fill in the blanks. In Dungeon Master particularly, seeing those labyrinth later levels scrawled out on a WHSmith notepad often filled us with a sense of horror. We were so far from safety and anything resembling home.

Those are all physical maps though. What about in-game maps? They can be rather special too. There are user-generated ones, as in the please-God-why-won’t-they-port-it-to-PC Etrian Odyssey series. And there are those that the user can modify through the addition of notes. Ultima Underworld springs immediately to mind. I do talk about Ultima a lot when I’m waxing nostalgic. But my favourite map ever in-game map is the one in Silent Hill 2.

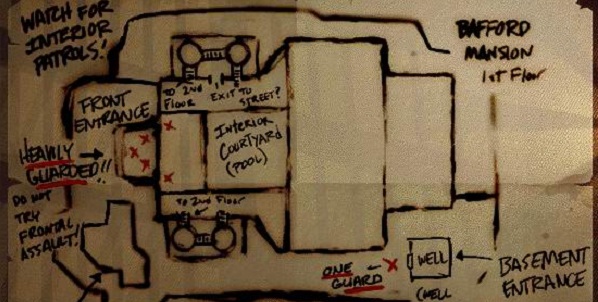

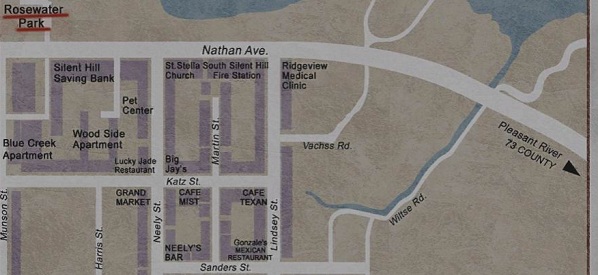

If you haven’t played it, it goes a little something like this. Nothing works like it should in Silent Hill (the town, not the game), so streets end in chasms and a hole might casually appear in the floor of an apartment. The lead character, James Sunderland, doesn’t work quite like he should either. He’s slightly confused but not as confused as you or I would be. It’s as if he almost expected all the rotten wrongness he’s experiencing. That’s reflected in the way he annotates his maps.

James doesn’t automatically have a map of each area, he has to find it. In an apartment building it might be stuck to the wall in the lobby, as may be the case in the real world. The problem is, that map shows the place as it should be, not as it is now that reality has shifted. It doesn’t reflect the space as you experience it. So, when a door suddenly ceases to be a door, James scribbles it out on the map. When a room takes on physically impossible proportions, James just scribbles out the walls. He does it quietly, without reaction to the madness of it all, so there’s no prompt to inform the player. But the next time you look at the map, you can see that he’s been updating it while you weren’t looking, taking the irrational and imposing what order he can on it. It’s brilliant because it takes a tool that’s primarily there to assist the player and makes it part of the psychological narrative.

I think there’s a reason my love of game maps is mostly fuelled by nostalgia and that’s because I couldn’t just jump on the internet to find information back in the day. I had my experiences in the game, the trinkets in the box, and that was it. Everything I could ever know was in there somewhere and I’d have to explore to find it. I’m not complaining about the vast swathes of information on the internet, especially not while I’m contributing to it, but there’s something about that sense of discovery, when I was the first to step into a world. Now, it’s hard to avoid the feeling that the legions of Gamefaqs have already been there and that I’m walking paths well-trodden.

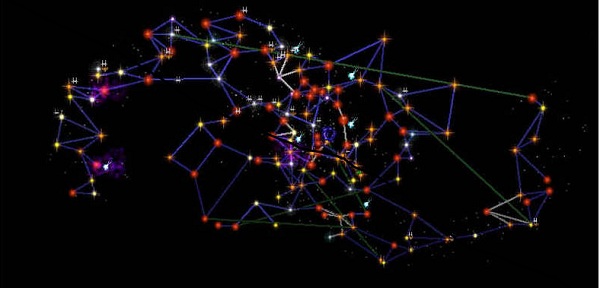

A couple of weeks ago I saw this, which provides yet another way of exploring the fictional. Many of us are already familiar with Street View as a tool for finding directions or indulging the morbid fascination of staring at childhood homes and dwelling too much on the past. Because of that, I find there's something uncanny about skimming through an unreal place using it, enhanced by the fact that, in a sense, I have walked and driven through the streets of Liberty City. There are other examples of created worlds being transposed onto Google Maps and I'm particularly interested in how this changes the way we view procedurally generated spaces. Displaying virtual spaces in new ways recaptures a little of those maps on my wall many years ago. There are still cloth maps to be had but I’m happy to see new ways of investigating the worlds I escape to.

We asked you about maps once before and it’s a subject lots of you had obviously thought about. I’m sure I’m not the only one who finds the world generation in Dwarf Fortress a source of wonder almost as great as the complex machinery of the simulation itself, or who enjoys strategy games partly because it’s joyous just to watch the map change colour as borders shift and factions crumble. Any game that shows a replay of events on a map afterwards becomes seven times more pleasing when I get to the end. They tell us stories, these imagined topographies, and they become repositories for the stories we create. And there’s something pleasing about the fact that what is designed to ensure we don’t get lost is often the thing that helps us lose ourselves completely.

Here’s to maps. Not just for their utility but for their position at the foundation of so many worlds.