The Lives Of NPCs

What's in the NPC box?

While at a procedural generation shindig for ProcJam, roguelike developer Darren Grey answered a question about games which have characters who interact with one another and not the player. A member of the audience suggested Din's Curse and Depths of Peril.

"I don't know how interesting that is - having things interacting with each other - especially if they're out of your sight. What does it matter? A game should be player-centred in my opinion. I'm not interested in what goes on behind – simulate it. make it up, it doesn't matter. As long as the player feels like they're getting an interesting experience."

It's an answer which stuck with me because it touches on ideas I find odd about game world creation.

I want to feel that worlds exist and have a degree of permanence beyond my purview. The player is the reason these things exist, because they're commercial products, but I feel like if you cater to that idea too slavishly you'll end up with weird dead worlds which only spring to life as the player moves into the vicinity.

The things I crave in games are stories, surprises and systems. With an RPG the hero story might have the most monsters or lend itself to the most bombastic box blurb, but ultimately it tends to follow the same familiar trajectory. Humble beginnings, a wise dude sees a spark of promise and is avuncular at you for a bit, a path of increasingly difficult missions which lead you to world-wide renown, final act of heroism (might be tragic).

Those stories are pleasing when told well, but part of that is giving a sense of weight and consequence to other characters and the environment itself. That same sense of a rounded-out world is also what makes other types of story possible.

I have a bunch of Skyrim mods installed and one of my favourites is the one which gives you alternate starting points in the world. You character can then go and join the main questline but you could also just go and live a life, unencumbered by the responsibilities chucked your way by fate. The existence of those new possibilities felt like it opened the game up in an interesting way, making Skyrim closer to a living, breathing world.

Going back to Grey, what he was saying wasn't exactly that this stuff doesn't matter, but that the process by which you create it doesn't matter. Ultimately you're looking for the player to have an interesting experience, so why spend time generating NPC interactions when you can conserve resources and use other systems to create the same effect?

With the Skyrim example, knowing the world now had a number of entry points and that some player characters might entirely avoid being recognised as the last Dragonborn was important. There was no longer a single funnel into the world, nor a single pathway through it and that was important to me.

As ex-PC Gamer writer Rich McCormick pointed out when we were discussing the idea, "I think you feel more like a hero when the world feels like it can exist without you. You can stamp your mark on a place that turns on its own; if it's built for you, then of course you can win."

Of course, it's all a con to some degree or another, because NPCs need to have their behaviours dictated by equations or tools. That's where AI or procedural generation or some other type of behavioural programming comes in. The difference is in whether the end result creates that living world feel.

I remember in Fallout 3 I always checked the items in people's pockets. Not in a scramble to just fill my inventory and wallet, but I mean I really checked them, trying to work out why these people would have been carrying those combinations of things and telling little stories about them. That was a direct result of Bethesda's world. The NPCs felt real enough that analysing pocket detritus from unnamed hostile mobs was a meaningful activity.

(If they had killed me and picked through my own inventory they would have found a lot of thumbs, cutlery and coffee mugs from nearby people I had killed.)

The reverse was true of Bioshock Infinite. Bioshock Infinite never felt like a living world to me, just a play being put on for my enjoyment, as though I was some cartoonish French aristocrat who had put forward a request for a game in which you make a lot of people's heads fall off (oh, the irony). Depending on what you think of the game's ending, that might seem apt or massively jarring in retrospect, but while playing I found it really irksome – a barrier to engagement and enjoyment.

There were some wonderful atmospheric moments in that game, but they tended to be closer to tableaux you could wander round. The rest was story sections punctuated by combat in the form of shooty busywork.

Probably the worst element in terms of generating a believable world in Bioshock Infinite was the scavenging system. Where I spent minutes pondering the pockets of lone Fallout 3 foes, Bioshock Infinite offered up a random assortment of gubbins in whatever receptacle happened to be nearby entirely to cater to the player's mechanical needs and with no kind of logic to their spawning.

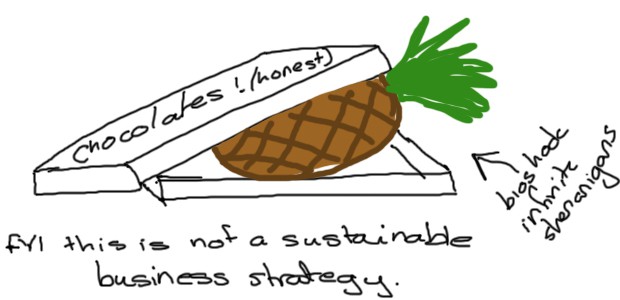

The closest I could get to making sense of any of it was when I got to the shop which sells boxes of chocolate. The looting system meant that when you opened them they were actually full of things like pineapples which wouldn't even match the dimensions of the container. I made sense of it by deciding the shop was run by a newly converted health fanatic, and that part of their approach was to trick their customers into eating fruit by fashioning pineapples into chocolate shapes and resealing the chocolate boxes.

For me, Bioshock Infinite was doing the opposite of what Grey advised. It had a system in place which had an effect on how I saw the NPCs. Ultimately it was intended as player-centric and helpful, but the way it had been implemented made for dull content; functional and divorced from the game's world and narrative. I didn't feel like I was getting an interesting experience.

Ultimately, when I'm playing a game the technical side of how an NPC came to act a certain way doesn't matter. What matters is the result. At their best these characters and the systems which underpin them form parts of the world capable of expanding the fiction or augmenting my enjoyment of it. They hold my interest. They give reasons for my own attempts to save or interact with the world. At their best, these mechanics are invisible. It's when they break that we remember we're in a game that's hankering for our engagement, and the world can suddenly seem so paper thin.

This article was funded by the RPS Supporter program.