Why Adventure Games Don’t Have To Suck: Ron Gilbert Talks Thimbleweed Park

More than a throwback

Yesterday, I spent forty five minutes with influential adventure game designer of yore Ron Gilbert. We played a portion of his point and click revival Thimbleweed Park and discussed adventure game design in depth. Many of my questions were inspired by Gilbert’s 1989 statement of intent, Why Adventure Games Suck. As Thimbleweed Park looks back to that time, it seemed appropriate to ask what has changed for the better. And for the worse.

A clown is scrubbing and clawing at his face, attempting to remove the pasty makeup and honking red nose that are the tools of his trade. He can’t. The clowning is no longer a costume, it has become his reality. Long live the new flesh.

Thimbleweed Park is an absurd, sinister, comedic point and click adventure that looks back to the golden age of Lucasarts, when its creator Ron Gilbert helped to forge many of the rules and standards of the genre. I spoke with Gilbert at GDC as he and programmer Jenn Sandercock walked me through a few scenes from the story’s first act.

It begins with the detectives, the two first playable characters, but the demonstration is all about Ransome the clown. He’s grotesque, in both appearance and character, an uncaring celebrity made famous by a stand-up routine that seems to consist entirely of heckling his own audience. The insults he slings aren’t creative or witty; they’re cruel, attacking any visible difference or perceived flaw for cheap laughs.

In a flashback sequence, he targets someone whose words have actual power and she responds by cursing him, making the cosmetic alterations that are the costume he hides behind a permanent fixture. Of the five playable characters in the game, three will be introduced through similar interactive flashback sequences, set in self-contained areas of the wider world. They’re origin stories, of a sort, explaining how these people came to be the (in one case literal) ghosts that haunt this derelict town.

An important part of Gilbert’s design ethos, as I understand it, is that every part of the game should serve every other part of the game. At its most basic level, that means a puzzle should inform the player about the state of the world, the progress of the plot, or the motivations and flaws of a character. In a more intricate sense, as it relates to the flashbacks, it requires the self-contained puzzles within to teach the player, ensuring that the kind of logic they’re discovering is applicable in the large, nonlinear area of the ‘present day’.

I hadn’t expected to find the game as weirdly charming and creepy as I did. The entire setup of Ransome’s life has its own peculiar logic that serves as an efficient cornerstone of worldbuilding. We’re in America - the diner, the feds and the store signs are confirmation - but this is an America where an Insult Clown is not only a celebrity, but an apparent A-lister, who can treat fans and employees with Hollywood disdain and fly from show to holiday home by private jet. He’s a rockstar and circus tents are the stadia and arenas of this world.

And, yes, Ransome’s introduction is funny, packed with gags that in the current build are delivered through uncannily well-timed text that leaves just the right pauses and hits all the right beats (voice acting will come later). It’s also weird though. Why a clown celebrity, I ask Gilbert.

“I’m a huge fan of David Lynch and, as you pointed out, the agent coming to a small town to investigate a murder is reminiscent of Twin Peaks.” The Lynchian influence isn’t just present in terms of nods, winks and allusions though. “What I love about Lynch is that he can show an ordinary situation, something calm and everyday, and skew it so that it becomes strange.”

Strange and sinister.

“Yeah. He only has to change one or two details to make something recognisable seem incomprehensible. Thimbleweed Park isn’t about the corpse you see at the beginning. I can’t tell you what it is about but it’s much bigger than that and you haven’t even seen the beginning of the real mystery yet.

“It is a dark story. Not as dark as some of the things in The Cave but it does have a serious quality to it. That’s been the case as long as I’ve been making games - look back to Monkey Island and it’s a serious story about a man who wants to become something better than what he is, a pirate in this case, but he is a flawed character. It’s a romance as much as anything else.”

Any story can become funny when seen through the right lens, perhaps. I’m reminded of the Mel Brooks line: “Tragedy is when I cut my finger. Comedy is when you fall into an open sewer and die.” Tragedy is when my aspirations are mocked and the person I love is abducted by a hideous undead brute. Comedy is when you make a point and click game about it. I suggest that point and click adventures have an inherent absurdity that can become comedic even unwittingly.

“I think you’re absolutely right. The way that you interact with the world and the things that you’re asked to do are often so unusual that it becomes amusing. If you need to open a door, you don’t get the key out of your pocket, there’s a whole sequence of convoluted events required to get where you need to be. If I don’t acknowledge the absurdity of that by having the characters respond humorously, the player will still recognise it.”

While we’re on the topic of convoluted and absurd things, it seems appropriate to ask Gilbert about puzzle design. I relate to good puzzle design in the same way that Justice Potter Stewart related to pornography: I find it hard to describe but I know it when I see it.

“An adventure game is like an onion.” Not that it should make you cry, The Walking Dead style, but in that it’s constructed of layers. “Every layer should feed into the ones around it. A good puzzle has to tell you something about the world, about the characters, about the mystery, about the plot. Too often, and I’ve been guilty of this myself, puzzles are used as roadblocks to slow you down and block your progress. Really they should be like signposts that you’re trying to decipher.

"In Thimbleweed Park we have a large world to explore and that can be intimidating so there are some obstacles to prevent you from going everywhere right at the start. But when you need to solve a puzzle to advance, that puzzle must have some context. When you solve it you should understand how and why it was necessary to do what you did in order to move forward and to open up a new area.”

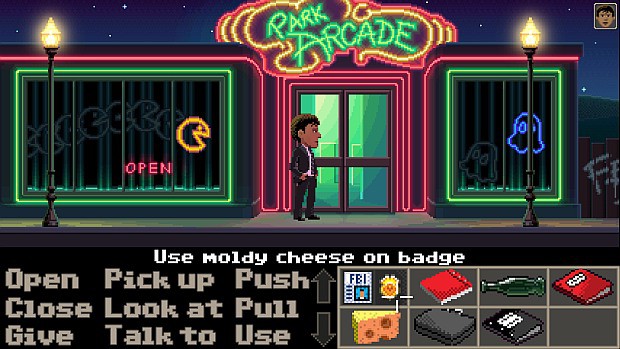

A good puzzle should also make you think. You should puzzle over it. This is one of the reasons Gilbert and his team have returned to a verb interface similar to that seen in his SCUMM days.

“I sometimes enjoy the simplicity of modern point and click interfaces but I like to make the player think and explore the world in more detail. If you can choose to push or pull something, or use it or look at it, you’re thinking about the specific way in which the character is interacting. It helps you to understand the interactivity rather than clicking on something and seeing an animation play out that shows something completely unexpected. Maybe you didn’t want to, or understand that you had to, act in such a way but the game does the thinking for you.”

For convenience, Thimbleweed does highlight a suggested verb when you hover the pointer over an object in the world, but you’re free to select any of the available options. And the suggestion is the most obvious choice - for a door, ‘open’ or ‘close’, for a person, ‘talk to’ - rather than the correct choice. Correct and obvious might be one and the same in most cases, but not always.

“Having these interactions, particularly ‘look at’, is a way to add details to the world as well as more jokes. And the jokes are adding detail to the world as well.”

The same is true of dialogue.

“The two agents have different dialogue trees and they’ll reveal more information about the people you’re talking to and the history of the town, as well as characters’ motivations and thoughts. You learn about the agents, who are working together for the first time and don’t always trust one another, by seeing how they read situations differently.”

I asked Gilbert if he can think of a single puzzle that he’s created that captures his thoughts as to how good design can work. One that he’s particularly proud of. He thinks for a while before answering.

“The faith puzzle in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is one of my favourites. The game tells you that if you need to have faith to walk across a ledge that seems impossible to cross. If you spend time clicking on things in the environment and trying to find a solution, you will fall. To cross, you need to ignore all of the usual puzzle interactions and just click the other side of the bridge.

In that sense, it’s not a complex puzzle but the player has to read the situation and understand the context of the world in order to solve it.”

That subversion of expectation is something that has been a part of Gilbert’s games since the beginning.

“With Maniac Mansion, we didn’t really know what we were doing. Monkey Island refined our ideas.” I’ve never been sure if the fake death scene in the first Monkey Island game, in which Guybrush falls to his apparent death, terrifying any players who haven’t saved recently before delivering a punchline that allows them to continue, was a jab at Maniac Mansion’s punishing design or a jab at rival developers Sierra, whose Quest games required a great deal of trial and error.

“It was mainly aimed at Sierra,” Gilbert says without hesitating. “That whole situation was so annoying because we made these games that encouraged players to explore and experiment and rewarded them, and we got better reviews, but Sierra would outsell us. They sold ten times as many games as we did sometimes.”

That’s not to say there isn’t an element of self-critique though. “With Monkey Island we were supposed to make a forty hour game. That was the requirement, seen as value for money. That leads to filler and puzzles that serve to frustrate and delay the player rather than to tell a good story.

"Thimbleweed Park is challenging, the verb system is part of that, but there’s an easy mode in which the harder puzzles will be solved for you. You still encounter them but the solutions are in place. Even if you’re playing in the regular mode, those puzzles form part of the story and characterisation though. Everything that you do has to fit in with the context of the plot and the world.”

The entire conversation changes my idea of what Thimbleweed Park is, or of what it is supposed to be. I’d thought, backed up by the notion that this is a throwback of sorts, that Thimbleweed was about returning to a golden age. Finding solutions by looking to the past where problems had already been solved and correcting decades of deviation from the correct course.

Gilbert’s views are far more complex.

“We want to make a game that is like your memories of those games. If you go back and play Maniac Mansion or Monkey Island now, they’re kind of crappy, and not necessarily as you remember them at all. We want to make a game like the thing that you remember rather than the thing that you played.”

The Lucasarts games, beloved though they are, were experiments. Not the ideal form of the adventure game but a process of discovery for the designers as well as the players. When he says that Thimbleweed Park should feel like the way you remember those games rather than they way they are, he isn’t simply talking about the addition of neat lighting effects and pixel graphics that are an improvement what could have been achieved on the machines of the time, he’s also talking about the design of the puzzles. And, perhaps most important of all, the storytelling.

“The behind the scenes fight in Monkey Island,” a scene in which a prolonged action sequence takes place entirely out of sight, “had originally been planned as a big visual setpiece. We didn’t have time to finish it so we came up with the solution of hiding the action and suggesting all of these things through on-screen text and visual cues. It turned out to be a great gag.

"Working within limitations is always helpful and makes you think of solutions that work. People sometimes say to me, what would you do if you had an infinite supply of money. What kind of game would you make? And I say, I wouldn’t make ANY game. I’d fuck it up.

"Good design needs limitations and flexibility. And that’s what we’re working within. It’s like a stage play, where you need to understand and work within the specific limitations of the set and the space.”

Thimbleweed Park will be out at the end of the year or early 2017.