Generation Next, Part 1: How Games Can Benefit From Procedurally Generated Lore

A four-part series on the future of procedural generation

Mark Johnson is the developer of Ultima Ratio Regum, an ANSI 4X roguelike in which the use of procedural generation extends beyond the creation of landscapes and dungeons to also dynamically create cultures, practices, social norms, rituals, beliefs, concepts, and myths. This is the first in a four part series examining what generating this kind of social detail can bring to games.

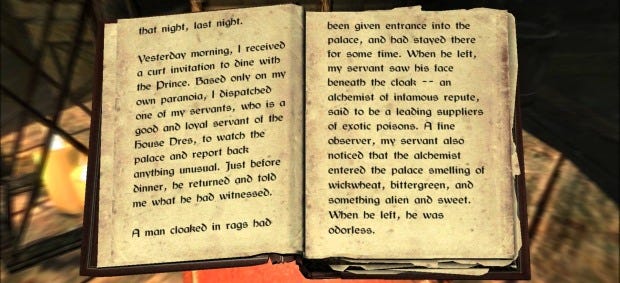

In Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage, a 2015 scholarly work by Erik Champion, a very intriguing point is made about the books in the Elder Scrolls series. In considering the interactive options given to the player, and the detail of the “lore” books the player can encounter, Champion argues that the books in the Elder Scrolls series describe a far richer world than the player is actually able to engage with. He proposes that the fiction in these works speaks to a social world with a grander possibility space, and a set of more detailed cultural, social and religious elements, than the fiction the player is able to create through their actions. Elder Scrolls books speak of remarkable unique stories with a tremendous scope of actors, events, cultures, and places; within the play of the games themselves, however, it is difficult to break out of several core gameplay loops of combat, conversation and exploration, to experience or even create the kinds of stories and social worlds we read about in the game’s libraries.

As well as feeding into this disconnect from gameplay, all this background world detail was hand-written, once, by the game’s developers. As deep and rich as many of the tales these books tell are, they remain the same no matter how many times the player starts the game. Few players will ever return to a previously-read book a second time, making their reading a one-off activity done at the start of the game, and even then something that most players gloss over, fully aware of the lack of immediate relevance to their character's experience that most books (except for “skill books” that raise your stats) actually have.

The intersection of these two concerns – their disconnect from the gameplay, and their unchanging nature – severely limits the social detail of the Elder Scrolls world to being only incidental, a backdrop, a player-created side-quest, or something to be considered once and then entirely forgotten. But what if such sociocultural detail could always be new and fresh, and always be actually reflected in the world(s) the player explores? Would players want to engage with this kind of detailed and always-distinctive worldbuilding, and how could worlds with those sorts of elements affect a player's actual experiences instead of being nothing more than background reading?

This four-part series will examine what procedural content generation (PCG) – a set of techniques for creating (game) content algorithmically rather than by hand – might be able to do for the creation of rich in-game social and cultural worlds, and how such procedurally-generated virtual worlds can offer far more gameplay relevance in their worldbuilding than their handmade cousins. PCG to date has tended to focus on generating spaces and areas of various sorts – we can witness this at many scales, ranging from the galaxies of No Man’s Sky, Stellaris and Aurora 4X, to the world maps of Civilization, Dwarf Fortress and Minecraft, and from the expansive dungeons of NetHack, The Binding of Isaac and Cogmind, to the individual buildings or streets of XCOM and Invisible, Inc. PCG outside those limits has explored the generation of narratives, puzzles, game mechanics, and in some cases entire games, but has tended to gloss over the generation of social or cultural detail of the sort related in your average Elder Scrolls book that tells of religious practices, historical events, everyday life, artistic or musical activity, scholarly enquiry, or theatrical performances.

When “sociology” gets a look-in in game design, it tends to follow a model of social-as-statistical – selecting a particular “policy” or “civic” gives an abstract boost to your civilization of some sort, as shown in most modern grand-strategy games. However, we can algorithmically create emergent and detailed in-game societies and cultures through what I’ve taken to calling qualitative procedural generation, and in the process achieve two goals: a far greater originality in sociocultural in-game elements and a far more convincing act of virtual worldbuilding. This opens up the potential for these elements to stop being backdrop and start to affect the world the player explores directly, and the possibilities and affordances of those worlds.

To begin, however, it’s important to have a quick overview of where games currently stand in this kind of sociological worldbuilding detail and its effects (if any) upon gameplay, which to my eyes comes in three flavours: histories and lore relating to the important events of a fictional world; in-game cultures; and in-game religions, beliefs, practices or political positions, which I’ll group under the heading of “ideologies” for this discussion.

Firstly, in-game histories. Role-playing games in particular are increasingly turning to rich historical detail in their worldbuilding endeavours, most often talking about ancient societies, cultures, wars, religions, and noteworthy people and ideas. In Elder Scrolls, as mentioned above, there is a history stretching across thousands of years underlying all the games, which is mostly acquired through reading the in-game books, and in some cases talking to particular individuals or performing certain quests. A different model is pursued in the Souls games where the player is given hundreds of fleeting glimpses of the game’s world through NPC comments, item descriptions and the environment through which they pass.

In these games the physical world itself is intricately tied to the world’s societies and history, and this kind of lore yields tens of thousands of forum threads dedicated to analysis of the fiction. In the Dragon Age and Mass Effect series players collect information for a “Codex” of data about their game-worlds through conversations with characters, finding items, or undertaking events that trigger the unlock of new knowledge; in many cases this information is quite closely connected to gameplay and can offer hints about combat or conversation strategies. Many other games use the “dropped documents” style of worldbuilding, whereby the player finds pieces of paper, or books, tapes, data files, or some other equivalent unit of data storage, as they progress through the game. These elements each give fragments of information about the game’s narrative, world, or both, and the player then builds up an idea of the game’s background fiction as they play.

Secondly, in-game cultures. Well-known examples can be found in grand strategy games of the Civilization and Europa Universalis ilk, where different cultures or nations serve both as markers of different players, methods for introducing and encouraging different styles of play (if different cultures have different abilities), and varying traits such as the inclination of an AI player towards war, peace, diplomacy, science, culture, and so forth. On games of this sort cultural traits are thereby condensed into a series of high-level global preferences for each faction.

Digital fictional cultures can also be found in MMO games. In EVE Online, for example, players choose from one of four factions – the fast and lightly-armoured Minmatar, the slow and heavily-armoured Amarr, the long-range sniping Caldari or the close-range brawling Gallente – who each have a large amount of cultural detail behind them to be found on the game’s website, Wiki, and forums. You’ll see that I’ve described the four cultures in gameplay terms; EVE’s worldbuilding blends the cultural practices of each faction (the Minmatar are quasi-nomadic, the Amarr absolutist and theocratic, etc) with their preferred gameplay style and the naming of their vessels, whilst also treating the four factions as the foundation of many of the game’s conflicts, the distribution of space and system territory, and what in-game communities players are likely to become a part of. A similar idea is present in World of Warcraft and many other MMOs where we see particular units, characters, abilities or items tethered to particular cultures, and players are encouraged to align with a specific culture.

Thirdly, religions and ideologies. Religions seem more common in games than detailed political ideologies of fictional factions, nations, or organizations, although both are present. For example, the Yevon religion in Final Fantasy X is the foundation behind much of the game’s story and is reflected in great detail in the actions of its characters and the places and monsters encountered during a playthrough. The Covenant religion in the Halo series, which believes the ancient “Forerunner” species had achieved godhead by transcending the material world through the use of the “Halo” devices (in fact deadly galaxy-sterilizing superweapons), serves as much of the narrative motivation for the series. In the God of War series classical Greek religion serves as the thematic and mythological foundation of the places, people and monsters the player encounters, but is presented as a reality rather than a set of theological beliefs. In Dead Space the player battles against the “Unitologist” religion, convinced that the human race should “converge” into the game’s zombie-like necromorphs, and their symbolism and iconography can be found throughout the series whilst their NPC agents advance the narratives and pose challenges to the player.

While religion is the dominant ideological vessel, there are also games of politics. Prominent examples include the many real-world nations in the Democracy series and other comparable games in the “government simulator” genre, and the ideologically-driven factions of Alpha Centauri (rigid militarist, deep ecological, authoritarian collectivist, anarcho-capitalist, techno-utopian, fanatical religiosity, and liberal democratic). In all of these cases, beliefs and ideologies serve as primary motivators for the games’ (sometimes fixed, sometimes emergent) narratives.

This is naturally a very terse overview of these elements in game worlds, but we can nevertheless see their increasing ubiquity and centrality to contemporary games. Some games have this worldbuilding layer in order to add detail and in turn, believability – making a world seem more alive, more worthy of the player’s time and engagement, and more accurately resembling some of the systems (political, religious, cultural) we see in the real world.

Worldbuilding also offers substantial roleplay potential for players who are less interested in the technical game mechanic elements of a game, but who might be more interested in exploring that fictional world’s social, cultural and narrative aspects. We can also see two basic models for player engagement with this sociological detail, according to what direct mechanical impact that detail has on the game world. In grand strategy games, a particular policy directly affects the technical specifics of play – such as “+X Gold Per Town” – rather than any deeper engagement with the kind of social structuration that terms like “Mercantilism” or “Serfdom” truly represent. On the other hand, many worldbuilding elements have no direct impact on play, but their discovery can become an additional play element for dedicated fans intrigued by the fictional universe. The hunt for lore can be an end in and of itself.

Despite online discussions around lore, fan-fiction, cosplayers who identify with characters, and even the popularity (or not) of spin-off books and films, it's very difficult to know whether the majority of players are actually interested in these social, thematic and cultural elements. If not the majority, does a sufficiently non-trivial volume of the player base care enough to make these worth including? On the one hand, there is a tremendous drive in many quarters for the creation of games with deep and affecting stories (seen by many as a route towards the greater cultural legitimation of the media form).

On the other hand, heavily story-driven and relatively gameplay-light games risk being disparaged as “walking simulators” or as “mere” interactive fiction, and concerns of gameplay still dominate the reviewing processes of most critics, design decisions of most professional developers, and purchase decisions of most players. Despite these latter points, I think a lot of players would criticize an RPG, for example, for lacking this kind of worldbuilding detail, even if they never directly engage with it – there is an expectation of detailed fiction that players want to know is present, even if they ignore it. Many players of the Souls series have little interest in the cultural and thematic elements of those game worlds compared to the tight and precise gameplay, but still acknowledge that their very lack of knowledge of the game’s lore, coupled with an understanding that such lore does exist, is important to the overall “feel” of the game as mysterious and cryptic and to the creation of a convincing virtual world.

As outlined as the start of this piece, however, this kind of social, cultural, religious or ideological worldbuilding tends to suffer from two problems – it is often (though certainly not always) disconnected from gameplay or otherwise abstracted out, and once read the first time, players almost never return to it on a subsequent playthrough. To aid our thinking about how worldbuilding might be more closely integrated with gameplay, and kept fresh and original, in the next three parts of this series I’ll examine in detail the possibility of procedurally-generated social, cultural and religious worldbuilding and what it can bring to both background detail and immediate gameplay. To do this I’ll consider my own work and the work of others in these areas; explore where the cutting-edge currently lies, and how that cutting-edge might move forward in the coming years; and summarize what this can bring to worldbuilding as both intriguing detail, and gameplay-relevant information.