Wot I Think: Pyre

The holy sport of Pyreball

A purgatorial fantasy sport is not the direction I expected Supergiant Games, creators of Bastion and Transistor, to go with their next game. Then again, expectations seem increasingly useless when it comes to a studio such as this. Pyre [official site] is set in a world where literacy is banned and punishable by exile – banishment to a dangerous land called the Downside, cut off from the home realm of the Commonwealth. This underworld is where you find yourself. But you soon make new friends and, to earn your freedom, you start to compete in a quasi-religious tournament of orb-throwing and goal-scoring.

The sport of Pyreball itself has caused me to curse and sigh many times, but I can’t accuse it of being uninventive. That goes double for the story of this band of exile-sinners, told through visual novel-style interjections and dialogue choices. It’s a great story. One I often wish didn’t have fantasy netball clinging to it.

The Spoilerless Part

I’m going to keep this part of the review as free from spoilers as possible. However, because so much of what makes the game interesting and worthy resides in the tale itself (and the demons and dogmen of the world) I’ll also be writing a little about that afterwards. Don’t worry, you’ll see the warning. But first of all, you should know that how I feel about Pyreball is not necessarily how I feel about Pyre.

To explain some things. The ball games themselves are called “rites” and hold a spiritual significance. But it’s also a recognisably sporty tournament. Half of the game sees you pottering about a large-but-limited world map in a wagon, talking to your team members – demons, humans, imps, anthropomorphic dogs – and deciding which route to take according to their sometimes conflicting advice. You often duck into the wagon itself, where characters will reveal their pasts, and where trinkets and useful objects slowly accumulate as you continue your journey. The other half of the game takes place on the field, in locations preordained by the stars. Here’s where you’ll play some holy sports. YEAH. But it doesn’t even matter if you win or lose, the tourney keeps on going.

The ball game itself is three-a-side. Each team starts with a pyre of 100 strength. You need to grab the ball (a “celestial orb”) and dive into your opponents flames with it to reduce the fire’s strength by a certain amount. Repeat this until someone’s fire is snuffed out like a cake candle. How much your foe’s fire wanes depends on the character you scored the “goal” with. A small character might only reduce it by 15 points, a larger character might reduce it by 30. The disadvantage to plunging into the pyre is that this character will now be “banished” until the next goal is scored (by whichever side), leaving the most recent scorer with only two players against three.

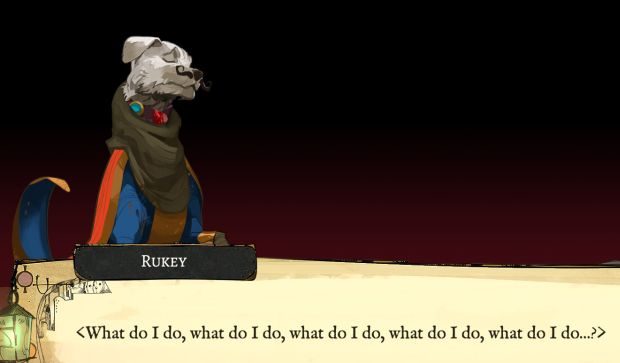

But there are other elements to keep in mind. Each player has an “aura” - a circular field around their feet which can “banish” another player that comes in range. Basically, they go in a sin bin for a few seconds, giving the other team more room and freedom to manoeuvre. The size of this aura differs between classes of player. For example, the large-but-slow demon Jodariel has a big aura and the small-but-quick dogman Rukey has a minuscule aura. So if they were to meet on the field as opponents, Jodie could simply walk into Rukedawg to banish him. Provided she can catch him. As I described it on the recent podcast, you’re basically moving Venn diagrams around while playing Weird Netball.

There are a lot of other small rules and elements. Your aura can be fired at opponents, like a wide, slow-moving laser. But its protective effects disappear completely if you are holding the ball, so you’re vulnerable while carrying it. Passing happens instantly, with no chance of dropping the orb or intercepting it. It just magically zooms, imperceptibly fast, from one player to another. And you can “shoot” the ball, by charging up a throw, with a little dotted line arc showing you the intended direction - scoring pyrepoints this way means you won’t be banished after a goal, since you didn’t immolate yourself along with the orb. Some player classes can also fly or hover over the field, but you can knock the ball from their arms by jumping into them. Your aura also disappears for a temporary moment if you jump – meaning you can’t just launch yourself into another player without zapping yourself in their own “grounded” aura, like a rogue chip flinging itself into the deep fryer.

But perhaps the most crucial rule is this: you can only move one player at a time. This is not like Pro Evo or NBA2K17, where uncontrolled players move at the computer’s behest until you possess them like some terrible footballing phantom. Here, you need to move and position each person yourself, keeping an eye on all three characters, while also striving for the goal and watching your opponent's formation.

I hope all this is enough explanation, because reciting a rule book makes for boring reading. I only want to give you some idea of how it plays, or how it feels to play. Because the truth is, it feels much better in-rulebook than it does in-game.

Much of that is down to controls and our expectations. The default keyboard and mouse scheme is a confusing affront to body memory. Holding the left mouse button moves your highlighted player forward – a control scheme I have long loathed and will never accept as feeling intuitive. The right mouse button throws the ball, spacebar flicks it between players, shift dashes, and the W key jumps. All of this combines in such a way that feels so contrary to years of moving little people around imaginary worlds. Perhaps it just doesn’t match anything in existence but my hands simply rebelled against it. “WHAT,” I hear them scream, as they jump head first into a foe’s aura. “Why are we using the W key, if we aren’t also using the ASD keys?” They stumble around the field, furious. “Why in the name of the holy scribes must we hold a mouse button down to move forward!?” They continue to hold the button in anger, as the demon Jodie tramples onward at the faltering pace of a dying rhino.

Mixing up controls and trying to establish a new kind of “literacy” for a game can be an admirable aim, but here it feels like the developers have gone against WASD convention for no real benefit. The controls don’t feel better, they don’t feel suited to a sports game, or any other game. Nor do they serve to add anything, or subvert your expectations or challenge you, a la Brothers: Tale of Two Sons, for instance. They just throw you off.

Luckily, a controller feels hundreds of times more straightforward and usable. But this only half-solves my problems. The sport itself still feels squiffy, although it’s hard to pinpoint why. The central problem I feel is that you only move one character at a time. The others just stand around in the last place you left them. This gives what should be a sport the feeling of a board game, or a tactics game, where pieces are sacrificed and left behind. Instead of an athletic game, where movement, speed, teamwork and agility should feel key, we have a game of starting and stopping, standing and swapping. The Book of Rites – an ancient lore text that lives in your wagon and describes the tournament - says “all move as one” but that’s not how this feels at all. It’s “one moves as one, and then another one moves as one, and then another one moves as one”.

Other annoying issues are small and more infrequent but nonetheless disruptive to the flow of Pyreball. You can get “caught” on certain bits of the field, especially at the bottom of the screen. The fields-of-play themselves vary, some with obstacles like fire pits or moving stones that block auras and obstruct movement. That variety of environment isn’t a problem in itself – it’s very welcome - but there are inconsistencies and quirks that irritate you mid-play. One field – a rainy shipwreck – sees your players jumping automatically over the holes. Another field – with a giant fiery unicorn corpse – has lava pits the same size and width but with invisible walls around them, no automatic jumping at all (and trust me, it’s better this way). Some fields have scrawls which simply look like lettering painted on the ground, something you’d expect from a heavily and beautifully illustrated game such as this. But these are actually impassable walls.

In other words, the sport Supergiant have made is an inventive and curious thing. It just doesn’t feel good. Much of it also has to do with readability – things will be slow and steady, then something will suddenly occur too fast for you to notice. Aura fields blending together, disappearing, reappearing, players dashing or blinking or throwing things at you while you search the field for the ball, where the hell is the ball? The sense of space on this angled plane is also often disorienting, especially when many players have vertical manoeuvres such as flight, hovering, or extra-long jumps. Sometimes you seem to pass right through the opponents flames. Other times, you land in the goal zone despite seeming like you were still a meter away from it.

Then there’s the existence of an overwhelmingly superior strategy. There is an advantage to having the big horn lady Jodie and other “strong” characters, in that they can boost your pyre’s health, cast bigger auras, chuck wider blasts of energy at opponents, and slam down with disruptive jumps. But I never felt those advantages outweighed the natural advantage of simply being quicker than everyone else, alternating between two fast characters and just diving into the pyre before the enemy even gets near the ball. It feels like there's an attempt to introduce a tactical dichotomy of speed vs strength in a game where there’s really only one way to play: be faster than your foe. You will mix up your triumvirate of players, yes, but this is for story reasons more than anything else, or out of necessity when some of your players get “banishment sickness”. In the end, I always made fast characters the linchpin of the trio.

Pyreball got less irritating the more I practiced and played. But I struggled until the end to get over that dislike, not of the sport itself, but of the way it felt in my hands, the way it hiccuped and faltered and twitched. When I think of fantasy sports, I think of Rocket League, a game that feels uniformly good every time, win or lose, an arcadey game of predictable and stable mechanics. But Pyreball is a wobbly sport you just play to proceed in an otherwise intriguing storyline, and where RPG elements have been stapled on in a contrived manner (There are stats and numbers behind it all, of course. Your “Glory” stat determines how much a character reduces their opponent’s flame by when they dive in. “Presence” dictates how wide their player-busting aura looms out from under them). It’s a game of fantasy netball that expects you to bump stats, mix up characters and abilities, counter special global effects or obstacles, and equip talismans and stuff for extra boosts. But I found that none of this really matters if you just use the fast dog to score points every single time.

What we have in Pyreball, is an almost-sport. As a contest, it feels like it should be faster, more brutal, more twitchy (which is weirdly how it would definitely feel if there were three human players per team, each controlling a character of their own). But it’s finicky and exploitable. And at its usual pace, it feels like it would have worked better as some kind of a turn-based tactical thing. Given the huge focus on levelling characters up, picking new abilities, buffing them with potions and powering them up with necklaces, it’s a little baffling why this isn’t the route Supergiant took.

As it stands, Pyreball is not a game I’d recommend. As inventive as it sounds in the Book of Rites, and as much thought and detail has gone into the design, it simply doesn’t play well on the field.

But that’s Pyreball, not Pyre. On page two, we're going to talk about everything else.

Skip to the final paragraph for a non-spoilery conclusion about the sport, the story and the whole package.

The Spoilerful Part

The problem with Pyre is that it’s a clash of lyrics and music. I don’t mean actual music – the music in this world is wonderful, varied and probably worth listening to independently of the game. I mean the story and the mechanical components don’t complement each other very well at all. They are connected in a vital way, as I’ll soon explain, but apart from some critical moments of decision-making, the wordy world of the Downside and the sportsball of the Rites just don’t gel.

Let’s talk about that world. The writing, being Supergiant, is the good sort of fantasy fluff. And it has naming conventions that’d be welcome in any Souls game. The “Bog Star”, “Wyrm Gulf”, “Slugmarket”, the “Hulk of Ores”, the “Nightwings”, “Deathless Tempest”. The lore of this world oscillates between being curious-sounding myth-history delivered by the Book of Rites (that tome sitting in your wagon) and character imparted world-building. You’re always seeking to know more, exploring a purgatorial landscape full of titan bones and diverse creatures, a physical place that can only be escaped meta-physically, via some ancient ritual of skill and valour.

The cast, meanwhile, could easily be dismissed as being a gang of JRPG staples. They are, in more ways than one, a literal bandwagon. There’s the happy-go-lucky girl, cute animal companion, anthropomorphic rogue, brooding strongwoman, mysterious cloaked figure who seems to know more than everyone else yet will never impart his full wisdom. The list goes on. But there is comfort in these tropes for childmen such as I, and the characters here do endear themselves to you in simple but effective ways. One shows fear at a creditor, another paces back and forth with worry for another character’s seasickness, three more sit and reminisce as a group about times long since past. One of them, perhaps the most unjustly treated of the bunch, befriends you with her wry behaviour, before rejecting you out of fear of closeness – and you find yourself thinking that she can’t really be blamed. There is a kinship in this rickety wagon of sportspriests, so much so that I find myself missing some of the characters now that it’s over. And I was even missing some of them during the course of the game, because Pyre’s most intelligent move is that it makes you get rid of your own team.

It works like this: when you finally reach the summit of a high mountain, having played in the tournament against several other “triumvirates” - each of whom have their own characters and motives, all generally well-written and some of whom are even themselves likeable – you discover that only one person is allowed to go free (and only if you win a final match). It’s up to you, as the Reader, to decide who goes and who stays. But you can only pick someone “worthy”. That is, someone who has played enough (levelled up enough) to deserve it. You’ll get the chance to do this “liberation rite” again and again after each new tournament, but only a handful of times. Some of you will not make it out of the Downside.

This is a wonderful idea. Imagine if that guy in XCOM came into your quarters and said “Hello, Commander. Please choose one of your best veteran soldiers to award with a happy life of retirement in a safe haven where they can live with their families and never feel fear or pain again. Oh, by the way, everyone else is stuck in the barracks until they die.”

How do you choose? Do you pick someone who you feel really deserves it, according to their own backstory or attitudes? Or do you elect somebody who deserves it less, just because you consider them less vital to the team and won’t miss them when they’re gone? And then there’s the added problem of friendship. What if you just like having this character around? Setting them free during one of the liberation rites means they won’t be there for the rest of the game’s plot. It’ll just be you, the wooden man and that bloody witch (this bloody witch actually has the best theme music in the game, so it’s not all bad).

But unlike XCOM, the dialogue and the character development make you feel for your team mates in a completely different, arguably mixed way. They are both resources – means of winning matches – but also people. People who’ve mostly been exiled and mistreated for unjust reasons, some of them staying so long in the downside that their figures have become roughened and demonised, growing horns and adopting permanently scowling eyes. You find yourself reluctant to let some of them go free, thumb hovering over the “Anoint” button, still unsure if you can face a Downside without their grumbling or their cooking or their stupid japes. And then there is the other conflict of emotions. What if your opponents also deserve their freedom? The opposing team during the final liberation match also has an appointed one who would go free should they win. What if you actually like your enemy?

Well, there’s absolutely nothing stopping you from throwing a game...

That’s another clever thing about the Pyre tournaments. Late in the game, you get access to a book that lists the ranking of each team. It transpires that your team, the Nightwings, are the team against which all others are judged. In other words, you will always play in the final. You’ll always get a chance to free somebody. But it also means that you can manipulate the rankings just by choosing a team and then purposefully losing, giving you some amount of control over exactly who you will face during the liberation rites. So if you really feel like the old dogman from team Fate deserves his freedom because, yes he’s your opponent, but he’s also a kind person and possibly close to death, there’s the chance to grant him that freedom at the expense of your own people.

It’s more complicated than that, of course. There’s a fellow on your team – a tree man who likes to smoke a pipe - who is formulating a plan to overthrow the entire system of illiterate justice on the “other side” by slowly releasing exiles loyal to this cause. The game’s story is clearly steering you towards accomplishing this goal. It forms the central plot and dialogue often displays a little percentage value of how likely "The Plan" is to succeed come the end of the game. You can increase that likelihood with each of your own freed people, but sometimes it remains more poetic, or even sensible, in a realpolitik kind of way, to let your enemies go free instead.

There are also smart parallels between the mythology of this world’s past and the revolution that your group of purgatorial sportsmonks are trying to achieve. Players and the lore scriptures are always referring to the godlike Scribes, “who gave their freedom so we could have ours”. Aside from being a hugely Christian sentiment (“he died for our sins”) it is also a reflection of your own fate. As the game nears its end, you know that some of your team will not be released from their purgatory. But that their actions and efforts in the arenas of the Downside will have resulted in the freedom of not just their fellow players but also the entire Commonwealth, who, if all goes to the wooden man’s plan, will be able to read books and never suffer exile or injustice again.

The Book of Rites is a particularly good depiction of how history may be warped into religion and how it often rhymes. You get the sense that these scribes were not gods or titan-killers. They were just the last bunch of Pyreball players to rebel, and slowly, as time went by, the Commonwealth they established decayed into its former practices of banishment and book-burning. This makes you wonder what the world of Pyre will be like 1000 years after the end of the game. It feels significant that, in the ending I got, the government established by the victorious rebels is called the “Sahrian Union”. There is a cycle at work here, although you never do see the whole circle.

Still, most of what is great about the story concerns individual characters, their motivations, their pasts, their intentions and the way they get along with each other. As with all parties that sally forth, your group of misfits have backstories and motives that slowly reveal themselves. A winged harp may be considered an enemy of the Commonwealth and an untrustworthy intruder, but secretly she harbours a deeper, personal reason for not seeming loyal to your own group of Pyreballahs.

This method of drawing out a story is one of Supergiants’ recognisable methods. It’s also, I’ve found, one of their biggest weaknesses, in the sense that they just can’t help but string things along far past the reader’s patience. There’s a point in Pyre, like in Bastion and Transistor, when you wish they’d just get on with it. The last few hours of this tale are especially heel-dragging, and I found each successive Pyreball match more and more frustrating, not only because of the problems with the sacred-sport I’ve already described, but also because I just wanted the story to reach its increasingly-obvious conclusion.

This tale of revolution, mercy, hope and choices could have been just as powerful and satisfying if it had been 5 or 6 hours shorter, even if that meant stripping out some of the more unnecessary characters, either characters whose stories don’t add much to the overarching tale or the Pyreball players who come later and feel like they’ve only been added to your roster out of necessity.

But the story is still good, is what I’ve been trying to say. And that one visual-novel style decision system of choosing who goes free does impact your upcoming games of Pyreball in a way that feels meaningful, even if it doesn’t technically improve the sport itself. Very late in the game I had to change my style of play to accommodate new characters, giving up on the superfast technique of my doggy pal in order to set the fella free. This didn’t make the sport itself feel any less fiddly and incomplete but it did make me think: “Oh man, I miss Rukey Greentail.”

And that, I think is the goal of Pyre. It wants you to recognise that people are not there necessarily so that you can Win Win Win, that others, even your enemies, sometimes deserve their desires over your own machinations. There are messages woven into the tale about justice, mercy, forgiveness, and liberty in a way that few games even attempt to cover. And I haven’t mentioned once how stunning the whole thing looks – I barely even need to say that. I only wish that the mechanics and feeling of Pyreball lived up to that strong storytelling, because it so often feels like an interruption to a great tale. But even I, who just rambled for thousands of words about how busted and rubbish I think the sport is, can forgive the game its flaws. Many people won’t get past those flaws (and I'm not sure I would have, had I not needed to review it) but those who play until the end will doubtless be moved by the plight of this particular bandwagon.