The Flare Path: Emotionally Authentic

Luke Hughes on war, wargaming, and the Burden of Command

Because Luke Hughes has a master's degree in neurophysiology and psychology from Oxford, and uses terms like “emotional authenticity” when talking about his upcoming “leadership RPG” Burden of Command, I reached for my little tin of Big Questions when preparing today's interview. Amongst the sensitive subjects discussed below: the glorification of war through video games, swearing on virtual battlefields, and why players of XCOM resemble seagulls.

RPS: How are you hoping to achieve “emotional authenticity” in Burden of Command?

Luke: By making it first and foremost a human experience rather than a tactics and strategy experience. Thanks primarily to permadeath, death has real significance in Burden of Command.

Permadeath matters not just because your player character might die but because as a leader you have to think about your NPC lieutenants and enlisted men’s deaths. You will have to consciously send men you’ve grown to like and respect into harm’s way. If they don’t come back, you can’t just reload and bring them back. Time and again vets on the team, including ones with combat tours behind them, have emphasized the importance of this aspect of command. What we call Men versus the Mission. This War of Mine, Darkest Dungeon, XCOM and of course more traditional roguelikes have employed this mechanic, but here we use it to make you think about the virtual lives you hold in your hands, not just your own.

Of course if you don’t give a damn about them and view them only as sprites this will fall a bit flat. So as a second technique we use ‘choose your own adventure’ like leadership moments. These seek to focus you on the Burdens of Command by presenting you with tough and often very historical choices. Not only Men vs Mission but for example, your men versus say the fate of other men (e.g. do you hold the hill at terrible cost so a different company is not outflanked?) What about the lives of civilians caught in the crossfire? Or even those of the enemy when the opportunity for perhaps too needless a slaughter is offered (like the still debated Highway of Death in the first Gulf War). When is it right to offer up your own life, ending your avatar’s career?

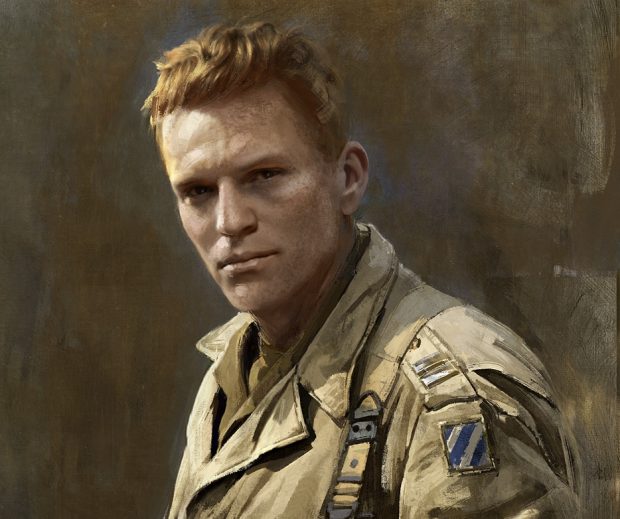

Context-linked character outbursts (“barks”) and the wonderful portraits created by Mariusz Kozik regularly appear on the screen further humanising your troops.

Finally, we try to center the tactical battlefield mechanics around human psychology: Morale, Suppression, Trust, Respect, Experience, and what might be called of the natural human “fear of death.” We try to create emotionally authentic battlefield mechanics.

RPS: Computer wargames have got by with simple morale variables and leader proximity buffs for decades. Why go deeper?

Luke: Why is a wargame experience only about tactics? The founding father of tactical wargames, Squad Leader’s John Hill once wrote:

"Squad Leader was a success for one reason: it personalized the board game in a World War II environment. Take the "leaders," or persons, away from it and it becomes a bore. Though this may sound surprising, the game has much in common with Dungeons & Dragons. In both games, things tend to go wrong, and being caught moving in the street by a heavy machinegun is like being caught by a people-eating dragon. Squad Leader was successful because, underneath all its World War II technology, it is an adventure game, indeed Dungeons & Dragons in the streets of Stalingrad."

Since then we’ve largely lost sight of his insight and left the roleplaying and emotional experience to the dice (“Snake Eyes! My squad just went berserk right as you charged across the street.. Oh man it just took out… etc, etc”). Close Combat digitally went significantly further with psychologically modeled soldier sprites. Unfortunately the sprites died so quickly you never had time to form the emotional connections like real bands of brothers do.

Why not take John Hill’s D&D analogy seriously? What we do first is attempt to put you in the boots of an infantry captain in World War II. That’s why we brought in historian John McManus, have many vets on the team, and even hired an archivist to go into the US National Archives and retrieve actual after action reports written by the captains and lieutenants who were there at the time. We’re hoping that by emphasizing the personal emotional experience of being a wartime leader, with all the responsibilities and emotional burdens that entails, that we are doing a more authentic war game, not a less authentic one. Just like how This War of Mine conveyed some of the emotional experience of being civilians in a war zone.

That being said, “simple morale variables and leader proximity” go a darn long way on the tactical side. But in the 30 years since John Hill there has been a lot of fine thinking in tactical board games as well as digital ones (Steel Panthers, Close Combat, Command Ops, anyone?). Standing on the shoulders of those giants especially those in the boardgame space we believe we can emphasize even more emotionally authentic tactics and aspects of battlefield leadership. For example, many many tactical games both cardboard and digital focus on firepower even if on the surface they appear to focus on morale.

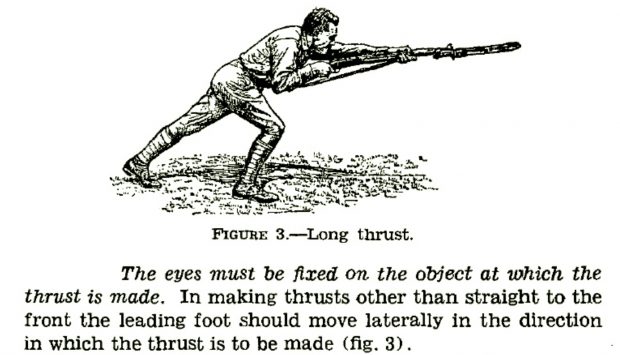

Typically you repeatedly fire at an enemy unit until it “breaks” and “routs” or is otherwise removed from the map through firepower alone. Firepower equals the “kill.” A fair statement for artillery but much less so for small arms fire. On real battlefields soldiers who weren’t panicking kept their heads down because they didn’t want to die. Would you stand up in the face of active machine gun fire to surrender or run away? I wouldn’t and they didn’t. Hence in WWII it took something like 8000 bullets to inflict a casualty. So instead you’ll need to close to assault a suppressed enemy.

But real warriors are usually reluctant to engage in hand to hand fighting. Leo Murray, the author of the superb book Brains & Bullets, estimates that left to their own devices fewer than 20% of soldiers are willing to commit to a hand to hand assault. It will be your burden as a leader to motivate that other 80% into finishing the job. For that you’ll need to have earned their trust by risking your own ass with them under fire. You can see how the human factors built on and off the battlefield come back to play a role in tactical mechanics.

I go into more detail on the mechanics of suppression, trust, and so forth in my latest dev blog.

RPS: War is a cruel, capricious creature so, surely, games that represent it accurately must be cruel and capricious too?

Luke: Random death was of course pervasive in World War II, and officer casualty rates were high. What you might call the all too real “physical authenticity” of the battlefield. So shouldn’t we just have your or your officers randomly die with frequency to be authentic? Well, two answers, first the casualty rates dropped significantly if you had battlefield experience. A lot of the casualties came on the first day or even moments of battle before soldiers had learnt to keep their head down, read the terrain, etc. Secondly, and perhaps more subtly, I think we need to juxtapose physical authenticity and emotional authenticity. Real soldiers form emotional bonds. Good leaders are often like fathers to their men, shepherds. And real soldiers have lots and lots of time off the battlefield to form those bonds. Remember the saying “war is 99% percent boredom and 1% sheer terror”? Well unless we plan a boredom simulator (probably not a sensible move from a sales perspective), we have to capture that emotional authenticity by reducing capricious death sufficiently to allow you to develop the emotional connection with your men that is part of the reward and burden of command.

All that being said if you insist on wandering around in the open in front of unsuppressed machine guns then yes you will experience the capriciousness of war. And sometimes even if you don’t act with folly. Though typically we’ll wound you and put out of action if you’re following good tactics rather than just kill you outright. Everyone is subject to permadeath in Burden of Command, including you. But we lighten up on the pedal to create the time for emotional authenticity and thereby an engaging gameplay experience.

RPS: Do you think games about war can glorify their subject thereby making real wars more socially acceptable?

Luke: As Robert E. Lee once said, “It is well war is so terrible or we should grow too fond of it.” Many wargamers, myself, among them, have sometimes felt concerned that, as I believe you once put it, we are playing in a graveyard. That we extract and focus on only the intellectual challenge of generalship and or the excitement and ‘glory’ of a well fought tactical battle. Similarly it is clear many people feel disquiet at the “power trip” that the endless offing of the enemy in a first-person shooter like Call of Duty creates. There is a place for the study of strategy and tactics and a place for escapist fun but there is also a place for an engaging experience touching on complex realities. The sales of games like This War of Mine - which explores the harsh realities of civilian experience in a warzone - suggests players of all kinds and not just wargamers might welcome engagement just as much as “fun.”

Interestingly I have never felt any disquiet working on Burden of Command. Quite the opposite, in fact, that perhaps we are doing some small service by showing respect for the realities of war and the burdens of leadership. Interestingly we have many vets on the team and among the playtesters, including some with combat experience, and while they are quick to point out that no game can really touch directly on the reality of combat, they also feel that Burden of Command, by being respectful of the emotional and leadership burdens of the real experience might do a service. Much like Band of Brothers, or American Sniper, if done well we can gain not only a sober sense of the challenges of war, but also a respect for those who endure it on our behalf. In short we can take away not the “glory of war” so much as a respect for those who serve and those who have served. Men like the Cottonbalers, the focus of our project.

RPS: Tactical wargames like BoC obviously can't show the disturbing visual reality of war but they could offer aural authenticity. Will there be F words and nerve-chafing screams in the game?

Luke: There weren’t going to be until you suggested it, Tim! But honestly, it’s an excellent idea. Our current plan is to have the writers Allen Gies and Paul Wang write many textual “barks” that trigger dynamically by situation and personalities involved to draw you into the “emotional action.” This War of Mine did a fine job on this. But if we can afford to do it on the auditory side for certain background human sounds like you suggest, that might be powerful.

RPS: I understand you've played the new CoD. If you'd been in a position to boost its realism in any single area prior to launch which area would you have chosen?

Luke: I'd have added respect for death. CoD does a remarkable job visually and with human characters setting the stage of war but then it pulls its punches through gameplay mechanics.

Right now in CoD your own death is only the inconvenience of a near instant reload. The NPCs around you are generally protected by “plot armor” meaning they have to stick around for the extended plot to be realized and the very expensive voice acting not to be wasted. Like Darkest Dungeon or This War of Mine I’d suggest taking the risk of giving it permadeath. Similarly, how can you experience the weight of war if your decisions can’t get others (the NPCs) killed? Look at how much players bond with the fanciful soldiers in XCOM or Battle Brothers. This comes back again to the core burdens of command, your irreversible responsibility over the life and death of others. Of course making such changes would mean a lot of other design changes for CoD (like procedural “levels” to make permadeath acceptable like in a roguelike). Not an easy task. It is our good fortune that we built Burden of Command from the ground up with emotional authenticity in mind.

RPS: The term 'hero' seems to be everywhere these days. Will there be heroes in Burden of Command and how will we know them when we encounter them?

Luke: Too often the a hero in a gaming context is someone who dispatches endless enemies with dramatic skill. In his book On Combat Colonel Grossman talks about certain men being “sheepdogs” meaning they see their role by contrast as the protection and welfare of others. Such men often make good leaders, like Captain Winters in Band of Brothers (a personal hero of mine). I always remember that scene where Winters decided to falsely attest to his superior to having sent out a second canal patrol at the end of the war to spare needless loss of life. However, I also remember many times where he had to order attacks that would likely kill men he respected and cared about because of the responsibilities of his role. In Burden of Command we similarly want to give you a role where you decide how you balance your mens’ futures versus your moral responsibility for the mission’s success. Where you have a chance to be a different kind of hero.

RPS: Does your knowledge of neurophysiology and psychology influence the way you design?

Luke: I tend to think about game design from the mindset of the “biological basis of behavior.” When Sid Meier says “games are a series of interesting decisions” I’m immediately thinking “what the heck is an “interesting decision” in biological terms? Well animals assess the world constantly in terms of “threats” and “opportunities.” I remember once watching a seagull I’d thrown some bread to… bread I threw deliberately close to me. It kept dancing into range of the bread (“opportunity!”) and then dancing back as it saw me too close (“threat!”). That seagull was dancing on the cusp of an “interesting decision.”

Guess what. Our biology as gamers isn’t any different. So when we realize in XCOM that if we move into the building this turn we’ll get to destroy the objective before the clock runs out (“opportunity!”) and then we realize there are probably Xenos hiding in the building (“threat!”) we suddenly find ourselves hovering on the cusp of an “interesting decision.” So in Burden of Command I try to make sure most tactical decisions involve an opportunity and a threat. Or at least two equally enticing opportunities where you get to pick only one. There the threat is the opportunity cost of the choice not taken. I push the writers to think similarly for the Choose Your Own Adventure decisions.

RPS: How have you prepared for your first foray into computer game design?

Luke: Well, I've sat at the feet of many virtual mentors during the past year. I've spent a lot of time watching Game Design Conference (GDC) talks on YouTube, listening to game design podcasts (shout out to Three Moves Ahead, Ludology Podcast, Dirk Knemeyer’s Game Design Round Table), and studying game players feedback in forums. I also spent a lot of time analyzing successful digital designs outside of wargames (XCOM, Crusader Kings 2, Banner Saga, This War of Mine, etc) to try to make myself think out of the (game)box about the wargaming genre. Then I read through all of William Bernhardt’s books on writing (the Red Sneakers series) to get myself educated on narrative design. We’re at a very fortunate time in the game industry when so many brilliant people are sharing their insights virtually. Finally I brought to the team of series of outside advisors and experts like Chris Avellone, Alexis Kennedy, William Bernhardt, well-known artists and more to advise us on good and visually appealing game design. So, well, we’ve been doing our homework. If our design falls short it won’t be from lack of trying!

RPS: Thank you for your time.

* * *

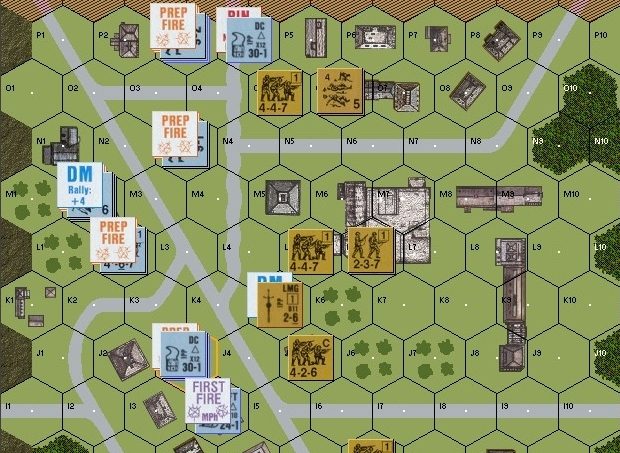

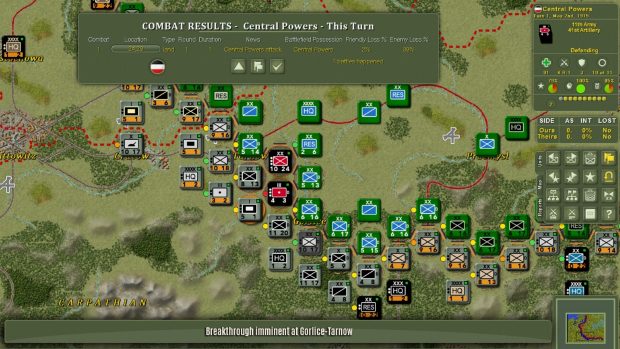

If Burden of Command has a polar opposite it's probably The Operational Art of War IV. Released yesterday, the most anticipated wargame of the year (according to its publisher, Matrix Games) is about as human/compassionate as a Czech hedgehog.

TOAW4 has much more important things to worry about than whether one wisecracking 18-year-old private from the Bronx steps on a Bouncing Betty near Aachen in 1944 while going to the aid of his wounded commander. Its concerns are generally brigade, division, or corps sized.

Capable of simulating almost any 21st, 20th or late-19th Century op, the TOAW series has been a genre favourite for almost twenty years. This latest version includes a reworked GUI, support for modern monitors, and realism advances in several areas including naval warfare and supply. A few quick-off-the-mark purchasers are clearly surprised and disappointed by the game's AI inconsistency (Some of the myriad scenarios feature a so-called Programmed Opponent ensuring challenge and historicism in singleplayer. Others rely on an incompetent generic understudy and are best suited to PBEM) but a slightly misleading feature list won't, I suspect, prevent TOAW IV from swelling the series' small but loyal fan base.

* * *