How Doki Doki Literature Club's subversive satire explores the power of visual novels

welcome to the club

What if your favorite game got removed from Steam, but nobody seemed to notice? That’s what happened to Muv-Luv Alternative, a nigh-hundred-hour visual novel from Japanese developers Age that some have called the magnum opus of the genre. It’s currently the highest-rated title on the Visual Novel Database, barely eclipsing the better-known Steins;Gate. But in January, the censored non-18+ version of the game disappeared from the Steam storefront without explanation, with members of the development team apparently scrambling to get it back up, using the discussion board to document their progress, or lack thereof. Very few sites reported the news, and understandably so: according to SteamSpy, this hyper-niche game with its adoring fanbase has sold just shy of 10,000 copies on Steam, roughly half of its predecessor.

Meanwhile, a newcomer to the genre, that broke many of the rules that epics like Muv-Luv follow, was reaching millions of people. This is the story of Doki Doki Literature Club.

Muv-Luv’s sales reflect a commercial reality on Steam and in the West: though many gamers know what visual novel are, the market for most of them remains extremely slim, especially for the exotica brought over from Japan. For many VN aficionados, there’s a single game that sucked them into the strange, static world of text boxes and sun-dappled imagery, but the journey past entry-level fare like Phoenix Wright and Danganronpa can be rather harrowing, especially due to the prevalence of extreme eroge in the space.

You probably haven’t heard of Muv-Luv but chances are you’re at least vaguely aware of Doki Doki. It received coverage from sites that wouldn’t normally spare a second thought for a visual novel, and became one of 2017’s talking points.

That’s precisely because of the rules that it breaks. Doki Doki is a brief excursion into a twisted version of the typical school-set romance and since its release last October, it has been downloaded more than 2.5 million times. It’s a success story on a level far beyond what followers of the VN scene expect even from break-away hits, and its success has been a surprise to VN developers and to creator Dan Salvato himself.

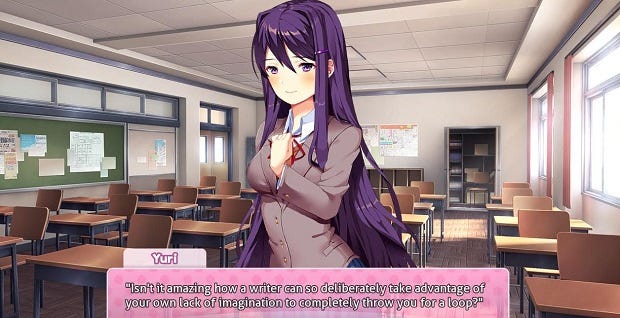

In short, Doki Doki is a self-effacing satire of treacly dating sims, and the fantasy fulfillment that they traffic in. You play as a nondescript Japanese high-schooler - a.k.a. the protagonist of 95% of all slice-of-life anime - who joins a literature club populated by four doe-eyed anime archetypes, each primed to swoon at your leisure. Once you pick your favorite through a charming “pick-the-word” minigame, the cogs of romance begin to turn swiftly, before suddenly delving into a nightmare world of trauma and horror which eventually - in classic VN fashion - leaks out and bursts the seams of the fourth-wall itself.

To hear Salvato tell it, the project that became DDLC came out of his growing frustration with what he views as the self-imposed limitations of visual novels, and a desire to share the form with the world. “I’m a fan of them, but not a fanatic,” he says. “There are other VN readers who have read five times as many as me. To me, what makes VNs really powerful is their ability to create empathy in the reader. My goal was to take that to a wider audience. But the response has been twenty times what I thought the best-case scenario could possibly be.”

To that end, Salvato decided to indulge in some design decisions that he knew would be anathema to the hardcore VN-reading audience in the West. Foremost among them was the length of the game. Most of the visual novels that Salvato affectionately refers to as the “top-tier” are at least twenty hours long - Doki Doki is tiny, in comparison.

Then there was the tone. While there are certainly exceptions, VNs tend to be mellower and more laidback in their pacing than audiences unfamiliar with them might expect. They’re content to saunter where others might sprint.

“I knew I wanted about an hour before the gimmick of the game reveals itself,” says Salvato. “If I tried to please the VN audience there, by giving them more time to get to know the characters, I would’ve lost the general audience. And [winning over that audience] was my overall goal.”

While certain design elements of Doki Doki have stoked ire within the VN community, a debate still rages on as to whether or not the game qualifies as a satire of the genre it has come to represent in the minds of so many first-time VN players. At first, Salvato takes great pains to paint the exaggerated pastel universe of Doki Doki as altogether normal, just like the ultra-generic games that inspired him. Even as that world breaks down around you, whirling through a morass of self-reference and meta-commentary, the game never turns its many knives against you, the player - rather, it’s the characters and the world itself that take the punishment, cracking open to reveal nothing but artifice. The game doesn’t tell you that its entire construction is empty wish-fulfillment, at least not directly - in his own words, Salvato wants you to determine that for yourself.

“People make fun of anime because it’s easy to make fun of these tropes,” he says. “I can’t accuse any culture of being more reliant than another when it comes to fanservice, or fantasy fulfillment. Western games have plenty of both. I think the reason people consider DDLC to be satire is that in anime, it’s the delicious, generic fantasy fulfillment that has become the meme. The game makes fun of these tropes, but it doesn’t condemn you for indulging in them. I didn’t have to try too hard to express the satire while I was making the game. Simply the fact that the game presents itself in a generic fashion makes it satirical to the community. To me, that’s what makes it satire.”

Though the VN community remains decidedly mixed on the subject of Salvato’s game, other visual novel developers regard DDLC’s massive success as a positive development for the genre. “Anything that can increase the number of players interested in the genre will help both new and veteran developers sell their games,” says Christopher “kiririn51” Ortiz, artist and designer of 2016’s cyberpunk VN hit Va-11 Hall-A, which itself served as an entry-point into the genre for many. “There might need to be a shake-up in the community. There’s an overall supportive environment, but there are some purists that are against innovation. Something as small as including a shooting scene in [Hideo Kojima’s cult classic] Policenauts is enough for them to dismiss a game as ‘not a VN.’ They have an idea of what a visual novel should be.”

For Salvato, though, the takeaway from DDLC is simple: he wanted to bring visual novels to a wide audience, and he undoubtedly succeeded. “I want people to understand the power than an interactive narrative can have, through connecting you to the characters. A lot of first-time VN readers got those elements out of DDLC, at least based on what I’ve heard through feedback. It’s not the exemplary 50-hour epic that avid VN readers want people to read. But, hopefully, through DDLC, more people will go out and commit to the larger VNs. I think it helps both developers and readers realize that there are other stories that do what DDLC has done, both inside the genre and not, maybe even better. And that’s what it’s all about, really.”

Doki Doki Literature Club is available now via Steam and is free.