A Panel Shaped Screen: remembering the sprite comics of the mid-2000s

Get ripped

If you're a digital artist, or have a friend who is a digital artist, then you're intimately familiar with the dread associated with the following phrase:

"Your job looks easy, the computer draws everything for you!"

Art is not a game, but games can help produce art. In the hand of capable webcomic artists, games can become brush and canvas and muse, and be ripped apart and glued together in new weird forms. Take sprite comics, for example.

Sprite comics are — guess what — comics made using videogame sprites instead of normal drawings. If you were a kid in the 2000s, you probably read some, like Bob and George or 8-bit Theater. Maybe you even made some, and then pretended to forget about them. Nowadays, sprite comics are remembered as something embarrassing we all liked when we were kids, but aren't cool anymore. They are still a big part of some communities, though, like the Sonic fandom, Megaman, Kirby and Pokemon games.

All those games feature simple character designs that can be easily altered to create your own characters. And while most aren't PC games, you can bet people were emulating them on PC to use them to make comics.

"My foray into sprite comics starts in late 2002, early 2003", recalls Pablo F. Quarta, former sprite comics author involved in the Sonic fandom. "My time on the Sonic Stadium Message Boards led me to discover a world of Sonic sprite comics, which seemed in the middle of a 'renaissance' of sorts; the recent release of the Game Boy Advance Sonic games had allowed comic artists to rip new, 32-bit, stylized sprite sheets of their favorite Sonic characters to update the old 16-bit Genesis ones they’d been using for years."

By "ripping" he means extracting art assets from a commercial game using a variety of tools and emulators. It's not exactly legal, but developers usually turn a blind eye as long as people don't profit from it. Ripped sprites are collected on databases like The Spriters Resource, a treasure pile for sprite artists, content creators and amateur developers.

Alas, old-school platformers often involve a great deal more punching than talking, meaning artists often have to edit ripped sprites to better suit their needs. An old Sonic game might contain hundreds of sprites of Sonic running, falling and jumping over enemies, but never show Sonic being sad, angry or surprised.

"In as far as where I got the sprites: most of them I got from sprite sheet websites and modified to make them into slightly more unique characters," explains Pablo. "A lot of recolouring and adding accessories and other details to help distinguish them. I never got too into making sprites entirely from scratch as other, more talented artists did."

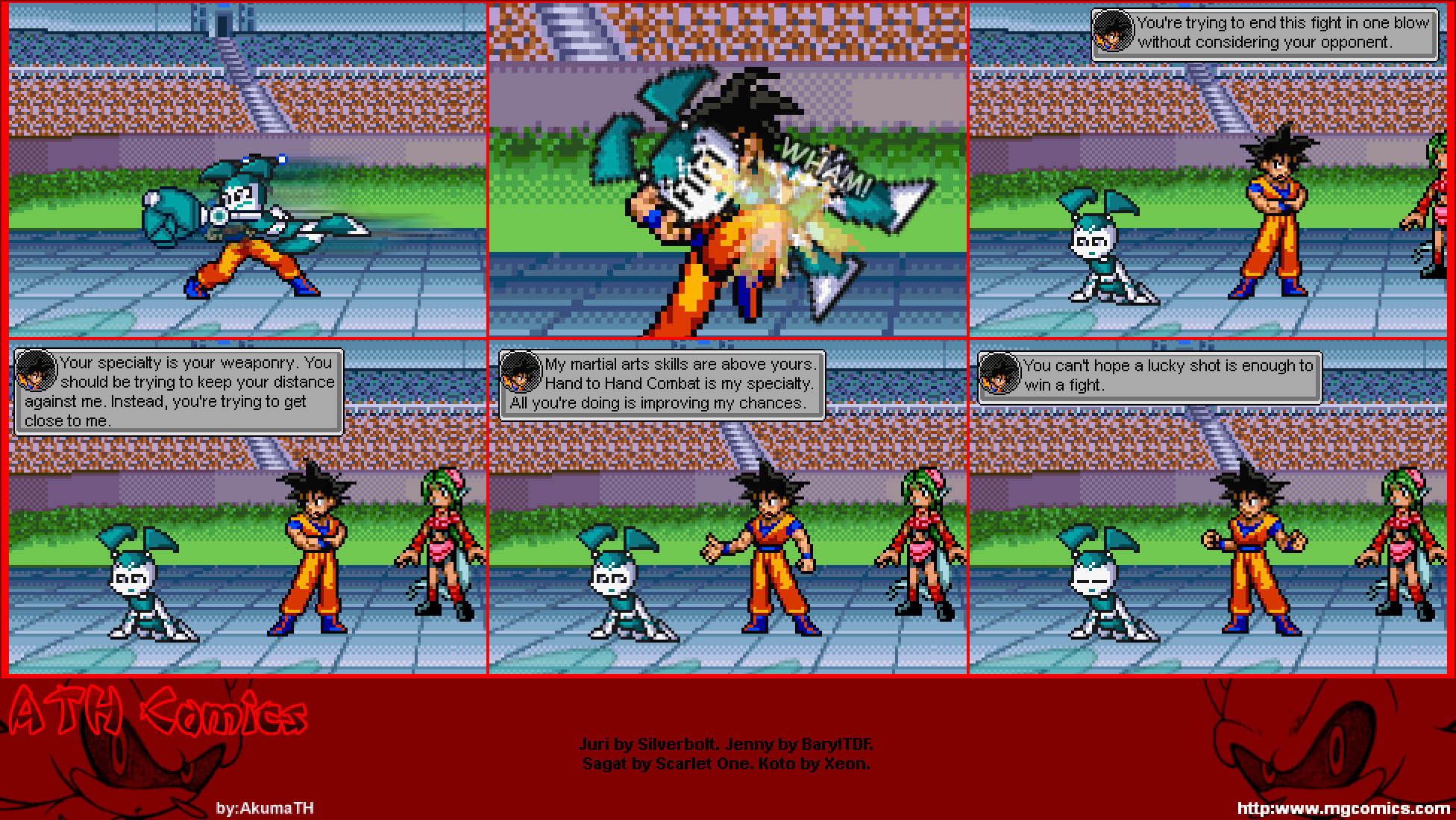

Where sprite comics lacked in art, they made up with inventiveness. Sometimes creators team up, like superheroes, as in the World Spriters Tournament, a series of collaborative comics where everyone can make up a fighter, create a sprite sheet, and pit their character against others' creations. The comics are made by different artists, and the results of each battle is decided by the community. I used to help organize tournaments and such in RP forums. At least one ended with a dramatic break-up, multiple people hating each other, and an entire forum getting deleted as an act of petty revenge.

World Spriters Tournament comics don't look impressive. Many would call them "lazy". I look at the disjointed pixels, and I tremble imagining the organizational effort required to create a single page.

As videogames evolved, new possibilities for self-expression opened up for wannabe comics artists. Some dress-up games allow players to create fake comic pages. You can find many on Rinmaru Games. Choose a page, customize the characters, add special effects and balloons. While you can’t really tell a story with a dress-up game, you can recreate the fantasy of making a comic. Dream that the original character you roleplay on Tumblr is actually the protagonist of a critically acclaimed comic series.

More elaborate tools, like Manga Maker Comipo and KumaKuma Manga Editor, allow users to customize, rotate and pose 3D models on a virtual comic page. It's a process more akin to playing dolls than to drawing, but by no means less creative.

Some artists work hard to overcome the tools' limitations, painting over virtual pages to polish the image and add their personal touch (an example: Snippets). Others fully embrace the wonkiness of the software, giving birth to trashy masterpieces like Kawaiikochan!! Gaming No Korner — a parody of both anime fans and of the dark, dark age of videogame-themed webcomics.

In the mid-2000s, roughly 50% of all webcomics were about two dudes on a couch talking about games. It's all Penny Arcade's fault, of course, for making their formula so appealing.

If you make a comic about two dudes on a couch talking about games, you only have to know how to draw two things: people and couches. You can insert yourself and your friends as characters, and string a plot out of your preferences and hot takes. Open this excellent Twitter thread if you are having an attack of masochistic nostalgia.

The explosion of post-Penny Arcade comics would merit a separate article. I don't miss that era, but it saddens me to see people pretend it didn't exist. It would be neat to see more comics about playing games — something with less sarcasm and a bit more joy. Perhaps we should just give Zeal all the money, and let them keep publishing personal videogame-themed essays in comics format. (Disclaimer: I wrote an article for Zeal last year. It was about smooching boys in a mobile game.)

You can make a comic about talking about games. Or you can completely disassemble a videogame, stringing together screenshots to create a story. Before streamers became a thing, text-based "Let's Plays" were (and are still) made this way. People would put together screens, dialogues, and comments to create something that is half-comic, half-script. It's more a form of storytelling compared to the video Let's Plays of today - more focused on narration than on performing.

This Let's Play comic of Princess Maker 2 by "SynthOrange", for example, simply adds dialogues between screens to add depth to an already charming simulation game. This Animal Crossing LP by "Chewbot" starts like a traditional LP, mixing captions with screens, only to replace screens altogether when the story goes so off the rails it becomes impossible to "act" in the game itself.

I know what you are thinking. "Giada, most of the comics you mentioned are quite rubbish". You're not wrong. And yet, that's exactly the point. Fan comics made with or about games are rarely literary masterpieces. They can be juvenile, rough, or plain unfunny.

But lack of quality doesn't equal to a lack of passion. It takes hours to assemble even the most basic-looking sprite comic, and many series went on for hundreds of pages. Let people make bad, goofy comics. Those artists are not professional - but they might end up becoming pros, if you let them. Professional artists like Tyson Hesse, who now draws official Sonic comics, began his career as a sprite comics creator.

Art is not a game, but it doesn't mean you always have to take it seriously.