Wot I Think: BattleBlock Theater

Block Party

Sprung from its imprisonment on Xbox, vaudevillian penitentiary platformer BattleBlock Theater has finally come to Steam. Its release is most definitely to be celebrated: BattleBlock matches shrewd puzzle construction with the furious pace and precise try-and-die challenge of Super Meat Boy, and yet fits all this in a difficulty curve so gentle you barely feel out of breath when you plant your flag at the top. The premise of each level - collect gems and reach the exit - may not be a stretch for the genre, but BattleBlock’s execution has few peers, plus it boasts co-op, both online and off, loads of competitive modes, mini-games, and a level editor with Steam Workshop support. And, because this is still a game from the makers of Castle Crashers, there’s a button which lets you fart yourself to death. Parp!

Let’s stay with the bum jokes for a moment. The first few hours of BattleBlock won’t win your heart on its awesome credentials as a piece of pure platform design, not least because the difficulty curve takes such a long time to take off you might be forgiven for thinking this was just a frivolous romp. Instead it’s all about the frivolous rump: though the mechanics don’t initially have a voice, internet-famous funny-word-speaker Will Stamper does, providing a constant maniacal narration which channels the Ren & Stimpy era of borderline-worksafe toilet humour. Stamper’s performance is so heroically entertaining it might singlehandedly save a much lesser game than this, interjecting with exclamations that are by turns snarky, sinister and silly.

Even if you are so mature as to find poop jokes resolutely unamusing, there is a joyous abandon to the way the lines are delivered that gives the game a responsive energy, as Stamper earnestly explains that the idea is not to die after a fatal pratfall, or simply shrieks, “OH MY GOD!” when you trim yourself on a saw blade. Even after nine hours in the singleplayer I was still hearing new lines and still chuckling. There’s a sort of freewheeling fun to it - the kind you can only get from indie studios, agile enough to seize upon an idea thought up while drinking beer and slap it in the game. Like, for example, the secret levels accompanied by Stamper scat-singing “It’s a secret!” with increasing feverishness. Stamper’s outro theme music, meanwhile, which might be considered a spoiler if it related to anything else in the game, is this marvellous paean to trouser security. (The entire soundtrack, which boasts contributions from the likes of Kid Koala and members of the Newgrounds community, is exceedingly eccentric and very hummable. The OST is to be released, apparently, though there is no certain date as yet.)

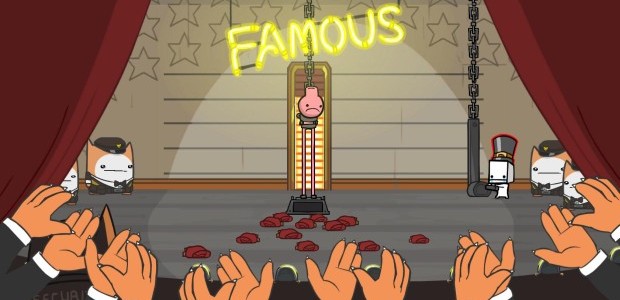

Who exactly this narrator is meant to be isn’t clear, but then the entire framing narrative, told via puppetshow cutscenes, is really no more than a cursory jumble of non sequiturs: you’re marooned on an island and imprisoned by a race of cats who force their captive charges to perform (and die) in a theatre run at the behest of a malevolent magical hat. The story knows it’s only there just to facilitate Stamper’s spittle-flecked chittering and the basic set-up for a series of deadly platforming challenges.

The levels are constructed of blocks, hence the name, and barring AI opponents, every obstacle or platforming appliance you might expect (saw blades, spring boards, wind turbines, etc.) has been compacted into a cube to fit within the level’s grid pattern. If this makes Battleblock feel a little inorganic and lacking the visual variety of other platformers, then at least it provides a toolset that can easily be wielded by community level designers. And the game squeezes a huge variety out of both its blocks and the ways they interact. There are ice blocks and spike blocks, of course, with predictable properties; blocks that propel you skywards; blocks that fling you sidewards; blocks that, when activated, project a light-bridge; blocks that toggle other blocks in and out of existence. They’re combined to create levels of meticulous design and compete with the barrage of ideas seen in the likes of Rayman, and other pre-eminent ambassadors for the genre, each idea itself spun out and elegantly escalated.

Levels often play with timing, establishing an apparatus of sawblades or other moving obstacles, that then trigger other blocks in rhythm: emitting deadly beams that in turn power a light-bridge, or cause a sequence of platforms to appear and disappear. Sticky blocks let you wall jump, and later levels combine these elements into an austere challenge, asking you to ricochet between sticky blocks, hang on wall-rungs and bound off platforms in their fleeting moment of existence in order to snag a gem and hit the next checkpoint - all while avoiding a cat’s cradle of intermittently activated lasers.

It’s not all just twitchy controller skills (and the game really does need a controller, I’m afraid), as later levels offer some head-scratchers, too, with some truly devious block-pushing, switch-flipping puzzles of procedure, and hidden gems that require a little bit of detective work to locate.

There are eight chapters in the singleplayer campaign with nine compulsory levels and a two-stage time-trial in each. There’s a further three optional levels per chapter, and secrets aplenty, with every level offering different degrees of success depending on the number of gems you attain and the speed with which you reach the exit - making the game unusually adaptive to different skill levels. There’s an extra incentive to doing well: collectibles are spent buying heads for your customisable character, or exchanged for handy weapons.

The game really lets you set your own challenge: even though it took me til the fourth tier before I graded anything less than an A, getting the A+ was a real test to my admittedly negligible speed-run skills. The tautness of each level’s design begs for you to return to it, to hoover up every missed gem while shaving seconds off your time. But even if your goal is to simply complete the levels, that difficulty curve begins to get a little slippery around the fifth tier, levels baiting you into imprudent actions that inadvertently lock off gems. By the eighth tier there are more than a few challenges that I would consider on the “total bastard” scale.

There’s a lot of room amid this content for people of every skill level, with an additional nightmare mode for players eager for punishment from the off, and a modified campaign purely for co-op. Adding a friend changes the flavour of the game, though, and not entirely for the better: the game demands well-timed cooperation but lends itself to chaotic self-sabotage, with players catching on each other or simply fumbling their sliver-thin cues to act. There’s fun to be had in griefing your companion, but it doesn’t get you very far. Similarly the other multiplayer modes are mostly brief entertainments, with the more aggressively competitive ones relying on Battleblock’s stodgy, reluctant combat. It’s a weakness in the campaign too - and a peculiar one given how lively combat felt in Castle Crashers. Here, enemies sometimes mob you and knock you repeatedly off your feet, giving you only a few moments to unhinge yourself from their collision box and initiate one of your own sticky, ineffectual punches. It’s not a lot better in multiplayer, despite an arsenal of bizarre weaponry, extending from bubble-guns to explosive gentleman frogs.

There’s a jolly but ephemeral pleasure in modes that pit you against an opposing team, each tasked with painting the level your colour, or dunking a basketball, even if they invariably descend into fisticuffs. But this stuff’s just the intermission ice cream - the main performance here is the singleplayer campaign. Castle Crashers showed the developers could make a game of splashily kinetic thrills and gleeful immaturity; Battleblock’s meticulous mechanical design, its taut level construction and soaring learning curve shows that they’ve grown up - if only in the ways that matter. Parp!