Premature Evaluation: CrossCode

Belle of the balls

Each week Marsh Davies jacks into the virtual battleground that is Early Access so that his spandex-clad avatar may wrestle with the digital monstrosities therein. This week he’s uploaded himself into CrossCode, a top down 16-bit-styled singleplayer ARPG set within a distant future MMO, where the boundaries between the real and virtual worlds have blurred.

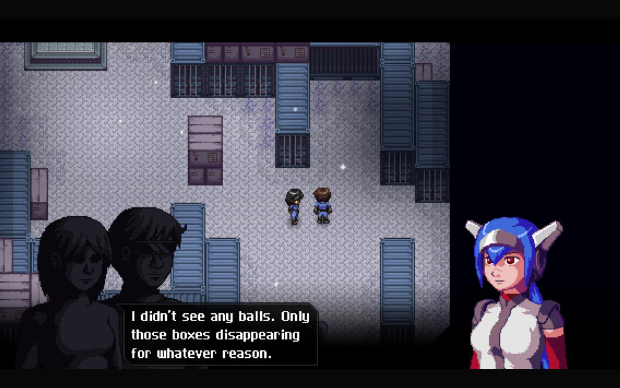

It is a strange vision of the future in which the world’s number one entertainment involves me slapping a hedgehog to death with my balls. These balls are sadly just glowing projectiles, of course, aimed in 360 degrees and fired continuously if desired, ricocheting off walls to hit enemies and switches out of the line-of-sight - but the game does insist on referring to them as “your balls” in a way which is either deadpan mischief or minor mistranslation from the developers’ native German. It is but one of many mysteries in the intriguing world of CrossCode - and a rather natty combat system to boot.

You play as Lea, a spheromancer class avatar - which is a better title than ballromancer at least - and is seemingly a part-flesh, part-virtual body, supposedly manipulated by some distant player. The game being played is CrossWorlds, an MMO which is like Tron mashed with The Crystal Maze and set in Centerparcs. Its hills, lakes and forests form a virtually augmented but otherwise physical space, maintained by a cast of humans who must don special visors to see all aspects of the reality in which you operate.

The MMO itself appears to have an ambiguous though clearly important role in this future culture, and its avatars inspire reactions veering between veneration and revilement. Though exactly who you are is unclear - a dramatic, playable prologue poses a huge number of questions as to your identity and purpose, which the ensuing game doesn’t look like it’s going to answer any time soon, since Lea loses both her memory and her voice. It’s a surprisingly multilayered fiction, which, despite the chirpy caricatures, feels like it might go bleakly Ghost in the Shell at any moment.

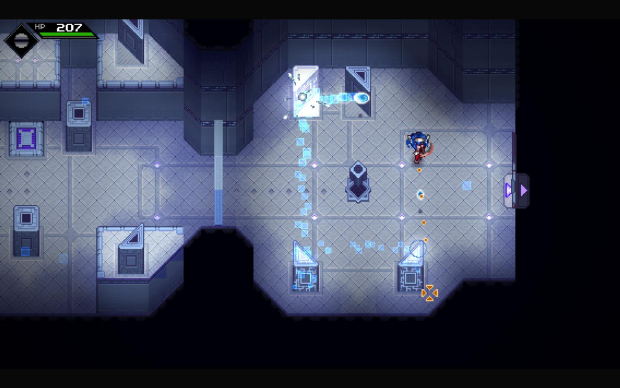

Currently this experience is split into three parts for the purposes of the Early Access build, which the developers are labelling as a demo. There’s a story mode, which includes a tutorial and prologue, a puzzle dungeon, featuring a lively but familiar mix of Zelda-style flip-switches, pressure plates and platforming, and an exploration mode, which lets you loose in the sprawling CrossWorlds countryside to slay hedgehogs, headphone-wearing meerkats and semi-mechanical buffalo.

As you do, you level up, unlocking an elaborate skill tree that upgrades your combat abilities in rather colorful ways. From the get-go, battles are frenetic affairs of split-second dodges and assiduously timed volleys and shields. Crowd control is key: enemies often cluster around you forcing you to dart between their ranks and kite them around the space, focussing down the weaker ones. Each have different vulnerabilities and attack sequences. Hedgehogs will periodically wind up into an invulnerable spin, bouncing towards you erratically; meerkats will burrow to a new location and hurl rocks; buffalo need to be tempted into ramming a wall before your bullets - sorry, “balls” - have any effect.

Aiming accurately takes a moment, and though it is perhaps less than a second for the potential scope of your shot to narrow to a single vector, in the chaos of battle such timing is critical. Knowing when to risk a volley of fire is even more important when enemies are capable of returning it; in places, CrossCode plays like a bullet hell shooter. On top of this basis come unlockable moves known as combat arts - like the ability to dive straight through enemies, dealing damage as you go - which are limited in use by a replenishing pool of charges. You can equip four at a time, one for each discipline - dodging, shielding, shooting and melee - though there are plenty to choose from as you mine the skill tree, creating an elaborate and hugely customisable moveset. And you’ll need it too: pretty quickly the number of enemies you fight exceed your ability to corral and kill them - AOE stuns and powerful charged shots become an essential part of survival.

It looks like the skill tree in the full game will quintuple in size, adding four branches of specialism and some sort of elemental system, too. But already, the game generously allows you to switch your investment instantly between symmetrical branches of unlocks - giving you a lot of leeway to experiment.

There’s more to this world than balls, though. There are items to harvest which can be turned into recipes and traded for weapons or equipment - though this all seems a bit bewilderingly random at present. NPCs have quests for you, too. Currently, one requires you to locate thirty-odd boxes hidden around the rolling hills of Autumn’s Rise, a leafy landscape comprised of 16 substantial contiguous locations and two challenge arenas. This takes the form of a sort of geographical puzzle - the boxes are often easy to spot but hard to reach: Lea can’t scale changes in elevation greater than her own height, though she’ll automatically bound across large gaps between pieces of terrain at the same level. And so you work backwards from the place you want to get to, unravelling the navigable route: a series of rocky stacks that will act as stepping stones; an escarpment you can leap down; a path implied, but hidden from the camera by a row of trees.

I would, however, say that the ingenuity of this sort of puzzle does not survive thirty-odd examples, and the game sorely, sorely needs a way to clearly distinguish between terrain at different heights. One of the features of this sort of perspective is its lack of foreshortening - there’s no way to judge depth and so if a stack of rock is four units tall, but one unit closer to the foreground than a stack of rock that is three units tall, their top surfaces will appear to be adjacent - and, if their height is concealed by another piece of scenery, there is no way to judge whether or not you will be able to jump between them. My ideal fix would be a subtle hue or brightness change for each tier of elevation.

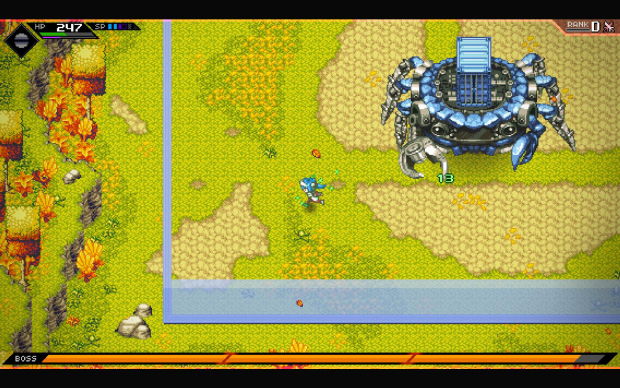

It also needs a way to track quests: I had no idea how many of these boxes I’d collected at any point and the NPC quest-giver gave no indication of how many I still needed. Doubly annoying was the fact that the final box was not to be found in the environment at all, but appears magically after killing a particular enemy, a blue hedgehog (ha ha), which itself only appears when you kill a bunch of other hedgehogs. Since this is not a mechanic ever explained or used elsewhere, I only managed it by accident. And the fight was a bit of a tedious slog, to be honest: despite the great agility afforded by all the customisable moves, some enemies just have huge healthbars and only one means of safely attacking them, whittling them down over many minutes. A couple or more buffalo together are the worst. Their giant metal skulls deflect your balls, forcing you to go at them from behind. But waiting for one to slam himself into a wall so you can unload on his bum, and then finding the opportunity to do so while evading the other buffalo, is expressly tedious. It becomes a combat encounter with no threat, only time, attached - and I found many of the lengthier battles fell into this category. My balls deserve better.

Nevertheless, there is a fair amount here to enjoy and admire already, and, in truth, few of my frustrations with the game so far are more than a single tweak away from being completely annulled. The next update will bring even more areas to explore, though what I really want are some answers: who am I? Who, if anyone, is playing “me”? Just discussing playing a game in which you play an unknown player playing someone else creates a rather enjoyable sense of narrative vertigo and I'm rather excited to see how far down the meta-hole the game will plunge. As to when these hedgehogs will learn to fear my balls as they should, there are some mysteries best left without revelation.

CrossCode is available from Steam for £15. I played the version with the Build ID 623829 on 20/06/2015.