Raised By Screens, Chapter 13: Doom

United in a tiny, harmless act of rebellion

Raised By Screens is probably the closest I’ll ever get to a memoir – glancing back at the games I played as a child in the order in which I remember playing them, and focusing on how I remember them rather than what they truly were. There will be errors and there will be interpretations that are simply wrong, because that’s how memory works.

Note - due to a silly error on my part, this chapter is out of chronological order. If I ever compile the series, this would become chapter 12 and the UFO Enemy Unknown essays 13 and 14.

As much as PC gaming was my escape, just about my only psychic refuge during the unhappiest years of my life, it didn't do me any social favours. Despite the great longevity and multiple resurgences of the PC as a gaming platform, there's a fundamental aesthetic difference which persists even to this day - the solitary, bespectacled man sat at an ugly desk, leaning into a small screen versus a pack of sociable fellows lounging on a sofa, gamepads in hand, hooting at a large television set. I'll defend the superiority of choice and inventiveness on PC with my dying breath, but it's just not cool, is it? I've long since ceased to care about such things, but as a schoolboy in the early 1990s, having a PC rather than a console was at least as much a curse as a blessing. The spod with his beige box. The fascination with specs and speeds, the absence of big, characterful mascots, the keyboard. It's as though I actively wanted to be an outcast.

And then Doom.

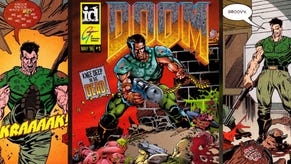

DOOM: KNEE-DEEP IN THE DEAD

1993, DOS

DEVELOPED BY ID SOFTWARE, PUBLISHED BY ID SOFTWARE/ GT INTERACTIVEPrototypical first person shooter, in which a human soldier battles assorted monsters on Mars. Initially sold as shareware - the first episode free, the subsequent two bought by mail order.

While there'd been some buzz around the earlier Wolfenstein 3D, Doom was the first game to really rise beyond PC gaming. It was rapidly famous in its own right, the media making it a parental bete noir and in turn as much a must-have for teenagers as any omnipresently-advertised Mario or Sonic sequel. So much killing, so much blood, sadism unbridled: in terms of cultural profile, Doom was the Grand Theft Auto of its time. And unlike most recent GTAs, there wasn't any sense, in practice, that it was trying to be controversial. It was a game about shooting monsters, and clearly loved being so. (It would be remiss of me here to not mention a notorious Edge review at the time, which chastised a game which was very obviously concerned with shooting monsters to not offer the option to talk to said monsters instead).

In the VGA flesh, Doom wasn't anything like as shocking or gruesome as either the newspapers or schoolyard legend had it. Even to my over-excited, gore-hungry 13-year-old-eyes, it was too bright and gaudy, too low-detail, too obviously a computer game to meet any claim that it was traumatic levels of violence with an unprecedented degree of photorealism. I was happy with that, because the pursuit of ever-bigger guns and encounters with ever-bigger monsters was what most enraptured me, but I was terribly disappointed that it wasn't the abjectly terrifying experience some peers had billed it as. Once in a while I'd start in surprise because an Imp popped out of a closet unexpectedly or there was a Cacodemon lurking at the close of a dead-end corridor, but fear never once came into it.

Nevertheless, Doom's pop-cultural light was luminous enough that, for a precious few weeks, I ceased to be a strange nerd who was ignored by most and bullied by a few, and instead a gateway to notoriety. Alas, my family lived in the sticks so I couldn't entertain a parade of blood-crazed visitors from the city - not least because no-one's parent was willingly going to spend an hour driving their son to play a game that the news said would warp his mind - but a couple of kids who I'd become passingly friendly with did find a way.

We cackled at the chainsaw, cheered for the rocket launcher, pointed in awe at the bloodied or murderous face of Doomguy at bottom-centre of the screen, and immediately embraced the Cacodemon as our next exercise book doodle. By this point, I'd also mended fences with my long-time best friend, after around a year in which we became enemies due to an argument over a Twix and his increasing preference for the company of an extremely snooty posh boy who was, if anything, even more unpopular than I was. All this was seismic at the time, and a source of great amusement for those peers who'd long seen our close friendship as pitiful, but of course today I can barely remember the details. He always had a better memory than me, but I can't ask him because he died of heart failure around ten years ago. Most of my best memories - including of Doom - involve him, and I live in fear of losing ever-more of them.

Like getting the school's colour printer - a very big deal then - to run off a few copies of Doom's title screen, which we'd painstakingly screenshotted, then pinning them to various notice boards around school, like some opaque act of guerilla art.

Like misunderstanding magazines' talk of online bulletin boards and becoming convinced that we could use the school's network to dial into some remote server to download the other episodes of Doom (of course, we only had the shareware version). We plugged random IP addresses into Windows 3.11's telephony application with no idea what we were doing, and never any outcome, but always breathless with excitement at the possibility that suddenly a copy of The Shores Of Hell would magically appear.

Like the one time we managed to get Doom installed on two PCs and play a networked game. We weren't the only ones to do so, prompting the school to fiercely limit the amount of disk space each pupil was allocated on its computers.

Like begging the young assistant teacher in the Technology room, whose PCs were more advanced and on their own private network to let us play Doom at lunchtimes. Like him agreeing, and joining in. Along with a great many other in-the-know pupils. We had a refuge from the sterness of teachers and the dullness of lessons. It was a silent protest group of sorts.

Exciting, uniting, not at all corrupting. But this sudden ease of access meant I and my PC were no longer special - Doom was everywhere, Doom was everyone's. It didn't take long before everyone mentally associating it with something they did at school made Doom in its entirety seem dull. It was a landmark, though. It's not that it made the PC cool - because that sure as hell didn't last long - but that, like Scorched Earth before it, it brought everyone at school together. United in gore, united in this tiny, harmless act of rebellion.

United in believing that games about shooting guns were and are the best games, too. Now that is a shame.

This feature was originally published as part of, and thanks to, The RPS Supporter Program.