State of the Art: How Isaac Cohen uses shimmering virtual cloth to explore emotions

All that shimmers

Over the last few months I've had a slow back-and-forth with Isaac Cohen – a game creator whose work caught my eye at GDC because it's got this wonderful experimental attitude to spaces and play. He also has these gorgeous textures and iridescent effects I haven't seen elsewhere. I wrote about my own experience of specific games Cohen made like Blarp and Warka Flarka Flim Flam, but with this I wanted to explore what he was creating from the designer's point of view.

Our emails ended up being quite long so I'm going to pluck out pieces which were of particular interest as we chatted – we started with the shimmering fabric effect that recurs across many of the games!

"As an artist who works in code, you can only really create using what's in your quiver of tricks. I've been doing 'gooiness' for so long, and realized I need to branch out to expand my arsenal. I started working on this cloth sim because of this piece of architecture I saw called the B-Mu Tower while reading the book 'Subnature' and found it to be so compelling to be able to see the faint ghost of a structure beneath a shimmering veil."

So that was the genesis of the idea.

"The thing about the digital world is that in general, compared to our reality, it kinda sucks. There's not very good resolution, if you are on a laptop it's just a window into that world, and if you are in VR, you are limited by space. The computation of even the best GPU is nothing compared to the simulations of reality, and we get ALL the senses, not just two of them.

"The thing that the digital world gives us is malleability, and extensibility. It lets us expand to realms that might have not before been possible. But still the physical world is one of utter majesty.

"What's so interesting to me is that in our march onwards into digital progress, so much of what the new technology allows is for the digital to become more physical, more humane. With VR, we get to move our bodies in more 'honest' ways, and with better GPUs our simulations can become more organic, more visceral. This to me is the essence of I want to be working on. Making computation more humane."

The logo Cohen uses for his Cabbibo work is part of that effort. It manifests at the start of each of the VR experiences I played and instead of just being a 2D or 3D shape hovering in space you make out the outlines via the way a piece of this digital opalescent fabric presses against them. It's like how you could lay a cloth over a shape and then blast it with a hairdryer to make out the edges. His own TL;DR summary is that "I wanted to create a logo that was not static, because this medium should not be static. It should be one that is reactive, flowing, alive." But the fuller version is interesting so I've kept it below:

"When we as humans interact with technology, magical things can happen, and it can become so much more than the strict, quantized, practical world we typically associated with computers. As well, it can reveal a world hidden to us. The logo itself (which to me represents self – Atman, not Brahman) is 'there' before the cloth hits it, but we cannot see it. The cloth reveals or points to something beneath it. We cannot tell exactly what that something is, but can see the implications. The shadows on a cave wall.

"Technology can be organic, emotional, vulnerable, even spiritual, if we choose to engage with it in this way."

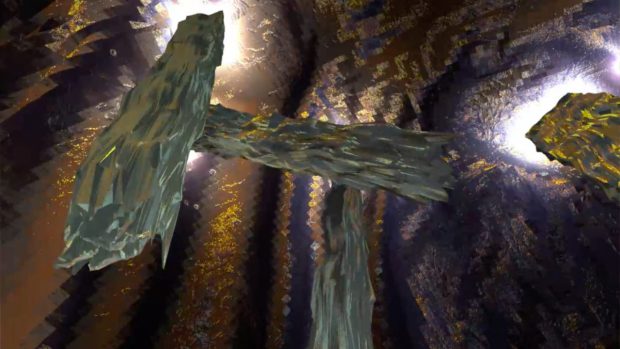

One of the experiences which stuck with me from his games – in fact the one I keep coming back to at odd moments because it was such a departure from how I'm used to people using VR technology – is in L U N E. You're moving these struts around and affecting how a piece of this shimmery fabric drapes across it above you. I had the delightful realisation that I was inside a slowly collapsing blanket fort. It's a small experience but the effect was powerful. I wanted to know where that project had come from.

Apparently it came just after Cohen had decided to step away from the Cabbibo name (having said what he wanted to say) and was contemplating potential next projects while spending a month in Iceland.

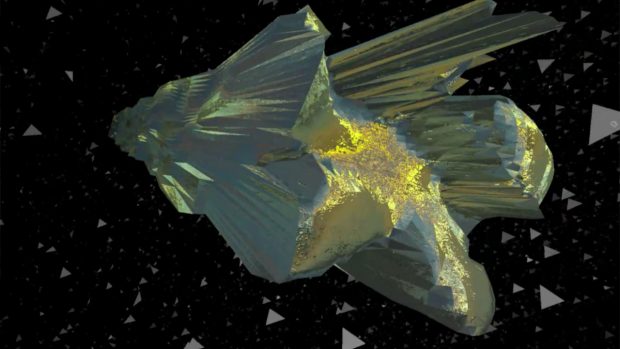

"It kept coming back to this concept of peaceful loneliness. I remember having this one conversation with a friend at one of those 3:00am Iceland sunrises. We talked about this object that we both kept trying to describe. The image I attached is the closest thing I've come to finding what I think it's like [Pip: It's this image of a quartz crystal cluster] , but there are some songs that feel like they describe the emotion a bit better (Come Down To Us - Burial , for example).

"The thing is that it's a bit more about the story surrounding the object then the object itself. It's strange because my friend and I both felt almost exactly the same story, and when I tell it to others, I feel like they really 'GET' it.

"It's like you are right next to this crystal, but so close you can't tell what it is. You can see the surface and facets, but it's so big that it doesn't feel like anything. As you start moving away from it though, you can begin to see more of its form, more if its shape. And the more you can tell what it is, the more beautiful it becomes.

"The thing is that the further and further away you drift, you begin to release how wondrous and miraculous the crystal is. You want to be next to it again, to be close with it now that you understand what it is, but you drifting further and further away, into the inky black ether.

"It's a pretty melancholy emotion, to see something so stunning, but to be moving away from it, instead of towards it, but it feels like there is still something peaceful about it."

He goes on to talk about the way that peaceful part can actually be quite difficult because it involves letting go in some capacity. It's an interesting reflection because my first impulse with the blanket fort in L U N E when I realised it was sinking was to try and build it back up which then made it sink more. I had to stop struggling to hold onto the experience in order to try and enjoy it as it moved to a conclusion. I think that was perhaps augmented by the fact I was in a timed appointment with no time to replay things – one shot was all I had and then they were gone.

The first version of L U N E wasn't actually what I played – it's a project which lives online and changes with each day of the lunar cycle. It's not interactive but it gradually moves away from you as you watch it so it explores the same theme.

Anyway, Cohen decided to keep the Cabbibo name and to continue to work under it but says his work took on a darker and more emotional bent. This was the same kind of time as he started to tinker with VR, designing the logo and playing around with cloth sims in those virtual spaces.

"I remember the first time I dropped the cloth, and it was just this perfectly flat plane. As it descended, I got kind of scared that it would squish me or I would have to avoid it. When it suddenly hit some block I placed though, this fear immediately evaporated, and the cloth just draped down, enveloping me in its warmth. This moment of going from alone in the abyss, to a giant square coming to squash me, to being totally enveloped, cloaked in comfort, hidden from the inky blackness surrounding me felt so so compelling.

"But even this was not enough. I figured I could just make an app where you drop a cloth over and over again, placing and creating structure in different ways, but at this time in my life, I didn't want to make an app. I wanted to make a poem. I wanted to make something that would try to touch on the divine, to speak about that object, moving away from it, and feeling the melancholy, peaceful loneliness."

That's a reflection after the fact. At the time, he says, it just didn't feel "complete".

"But one day, I accidentally made a change, making it so the rods didn't hold up the cloth any more, and it feel through them, through me, through the floor and just drifted down below, billowing and curling deep into the abyss. I remember crying the first time I watched it fall. For some reason it just spoke so specifically to that emotion of loneliness."

He then goes on to describe the effect I had when I played it:

"I knew that this would be the loop: quiet/peaceful playing in a field of stars, the fear of a brand new thing descending, the moment of wonder as fear turns to awe, being enveloped by love, the child like glee of creating a pillow fort, the sudden surprise of that thing falling away, and the melancholy nostalgia of the glee you just felt."

As part of my email I actually asked whether Cohen had tried a version of the experience where the fabric would drape over the player instead of passing through them.

"I tried to make it so the cloth could be repelled by your head, so you could be one of the things holding the cloak up, but I kept on getting these weird bugs where the cloth would then stick to you, and your eyesight would become nothing but shards of z-fighting triangles. Usually I would be ok with that and just leave the bug in, but peacefulness is a much more delicate emotion, and I needed to treat it with more nuance. I couldn't leave in as many rough corners to explore and discover as I would with something like 'My Lil' Donut'."

When I played Cohen's work at GDC it was in a strange environment. GDC is so odd and intense and you end up in these cavernous spaces with so much noise and stimulation. I actually had these Cabbibo experiences in an area behind a main escalator, so only a few feet from a vast stream of people, and with rushed journeys of my own to other venues bookending the appointment. I was actually a few minutes late for this and was thus also flustered and hot! I assumed that was a very different headspace to the one Cohen was in while working on the games.

I think VR headsets can be helpful in some ways for helping prime someone for a more delicate or quiet experience because of the sensory deprivation elements, but I was wondering what Cohen's own thoughts were on priming players/visitors to his spaces. I asked whether he wanted to exert some degree of control over that headspace or whether the variety players bring was more interesting?

"This is one of the strangest things about media to me in general. With all the talk about 'VR Storytelling' people from film love to talk about how it's hard to give up control as the creator. That you can't force a certain shot, or get a specific angle, viewers have freedom, and with that freedom comes a loss of ability to take viewers [along] this infinitely thin line through possibility space.

"I think that, as narrative game creators, for the most part we are past this point of "Oh my gosh, if people can do whatever they want how could I possibly tell a compelling story?" and have realized that when you manifest a world, it is your responsibility as a creator to make the universe and the possibility space of your story SO compelling that players *choose* to engage with your narrative, instead of being forced into it."

One of the examples he goes on to give is introducing people to videogames via the beautiful desert exploration of Journey – "I've never seen a single one of them not move towards the two pillars on the hill at the very beginning". But that's more about what people do once they're inside a game. The idea of priming someone for an experience is more about the act of engagement.

"There is of course always the assumption that the viewer *wants* to engage, but I think certain things like the Disney logo at the beginning of films helps sort of tell people 'OK! Here we go! Get ready to believe and participate in this reality!'

"Books might have a bit of weight to them, or be created in some way that the actual physical form helps tell people that its universe is about to begin. I just got this delightful book called the 'Codex Seraphinianus' [Pip: here's an article from Wired about the Codex Seraphinianus along with pictures so you can get the sense of what Cohen's talking about here] and just because it's this massive hardcover version of it, when I sit down I have to put in actual physical effort to open it. The pages have this deep texture that makes it come alive, that makes me turn the pages slower, that forces me into really believing or at the very least participating in the universe that book is creating.

"I don't really know if I've found a good solution to this in VR. The ritual of booting up your PC and putting on the headset I do think helps in some way, and for me immediately putting people in this dark environment with the logo hopefully gets the player to stop for a moment. I made the logo intentionally long, so that people have enough time to get bored with it, but than decide that they are still going to wait through it - that little moment of practiced patience is super important to me."

The best way of exhibiting his work so far, Cohen says, came with a pop-up project which was running at SFMOMA in spring 2017 to coincide with GDC being in town. If memory serves it was a version of his Ring Grub Island which was a little land mass with these fascinating elements to play with – weed-like trumpets you could pull on, grasses to brush a hand through, a curving tube to crawl into or peer round… You could also make it enormous or tiny, changing your relationship with the forms and how it was possible to interact with them.

"What was so special about it was the fact that Karenza Harris, an amazing person/architect from Morphosis, worked with Kate [Parsons] & Ben [Vance] to sculpt the *entire* experience of trying the pieces, not just once you put the headset on. They were shown in this separate room, through an innocuous-looking door, and there were actually actors who were hired to guide people through the experience. This was one of the joys of it being multiplayer too, is that the guide can move with you through the entire journey."

But even that experience wasn't perfect – for example, Cohen's intention was to minimise queuing, but that was unavoidable at times, and there were some issues with the mystic/occult card-giving element introduced for this specific installation.

The conversation then circled back to keeping people interested once they've stepped into your world.

"I have a rule for myself that every object in all of my experiences needs to be interactive somehow. I fail at it sometimes, but honestly even making it so that when you move your hand close to the object the shader does something weird, is enough to make that object pull you in deeper to the world. It moves from a static space that is separate from you and your world, to one you can inhabit, one that you can explore. I think that this helps to make the outside world fade away, as much as the red curtain opening at play, or the lights dimming at a concert and the dark figures walking out to take their places on the stage.

He adds:

"You can never expect [players] to have to [play], or that they will in the exact way you want them to. I think your best bet is to just try to make it so that the way they want to participate is conducive to the message you want to communicate, the experience you want them to have.

"The last thing I'll say is about your mention of variety. I do think that the juxtaposition of wherever someone is before they begin the experience and where they are once they are in it is pretty magical. I love the concept that people are going to bring whatever their views of the world are, whatever food they ate that day, whatever relationships they have into the experience."