The Necessary Bias Of Making A Murderer

Sympathy for an alleged devil

This is part of our new Saturday Supplement feature, in which RPS' writers run some bonus, non-gaming articles on weekends. Apart from this week, when it happened on Monday instead due to Adam ending up in hospital.

Contains spoilers for the entire series, though not in detail, and nothing that wasn't made public by news reports some years ago.

One of the hardest things about Making A Murderer - and there are a great many hard things about it - is the realisation upon finishing it that you mean nothing to it, or to the people in it. That it is not in any way your story.

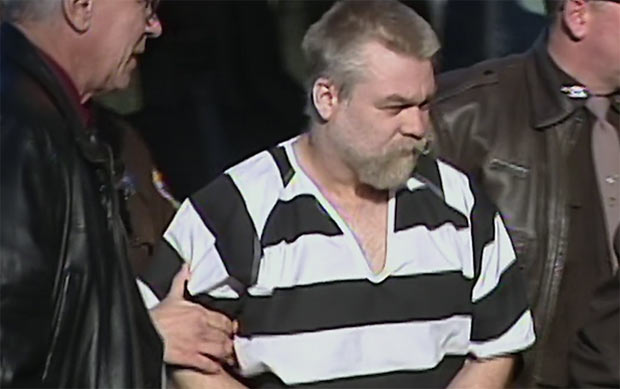

The Netflix 10-part documentary series focusing on the controversial twin convictions of Wisconsin scrapyard worker Steve Avery feels like such an intensely personal experience to watch - this marathon of faith and doubt, horror and hope. It's the drama of the journey, not the discomfort of the denouement that makes it, even though almost all discussion around the series is focused on that denouement.

To find coverage of and conversation about it everywhere once I'd finished was a shock, though not at all an unexpected one - clearly you're not going to find hidden gems on the front page of Netflix. I had much the same experience with Serial - it was my private headphone world of strangers' agonies, and to suddenly be sharing it with everyone else and their pet theories robbed me of that sense of involvement, stamped all over my own analysis of what might have really happened. A strange form of entitlement, that I should want to make someone else's tragedy feel like my own, and hate that it is taken from me by breathless headlines and all-knowing Tweets.

On the other hand, I'm typing 'Steve Avery' into Google every day and finding out new things - actual records of past evidence or evidence not shown in the series - which destabilise my own beliefs about Avery's innocence or guilt. Not just theories, but facts. And that means the show keeps on going, keeps on providing, in a way very few others have. Post-Serial analysis seemed so much more mired in gut theories, and particularly affected by the evident sympathy of its narrator, so upon realising that there was little else left to discover, I lost interest fast.

Making A Murderer has no blatant narrator, but there is a hidden one - selective editing, shaping the tale and shaping sympathies. As much as I am relatively convinced there was legal wrongdoing regardless of whether or not Avery was guilty, I find it deeply disingenuous of the film-makers to have claimed they made as balanced a series as possible when accused of bias by charmless prosecutor Ken Kratz.

I understand that Kratz, along with almost everyone else who maintained Avery's guilt, refused to contribute, thus inevitably meaning more footage of those on who his side was available to the cameras, but there's no escaping that long shots of sad mothers or kind-eyed, sighing defence attorneys would lead most viewers to draw sympathetic conclusions. If a cop accused of evidence-tampering wouldn't talk them, surely at least one friend, family member or former colleague would be prepared to stand up for them on camera? Where was the show's human sympathy for those who seemed to truly believe Avery was a monster?

It is a biased show. But perhaps it needed to be. Because there are two separate tales in it - one is the question of whether or not Steve Avery murdered a woman not long after being released from an 18 year sentence for a sexual assault that later DNA testing proved he did not commit. It's an incredible, delicious, chilling concept: not just did he do it, but was an innocent man framed twice? And if he was, was it because, as slowly-emerging post-show reports are lending some credence to, the police had very strong reasons to believe Avery was a danger to society? Was crime-scene tampering, if indeed it did happen, acceptable if it meant getting a monster off the streets? That's the question Making A Murderer doesn't actually pose, both because it cannot itself accuse the police of illegal action (it's reliant instead of what anyone else says on screen), and because it's very clear that its sympathies lie with Avery and his similarly-accused young cousin Brendan.

Brendan isn't the second tale I mean, although should be thought about separately to Avery. (I am more doubtful of his guilt than I am about Avery's, and as a parent seeing someone with childlike behaviour being coaxed into saying certain things while clearly unaware of what doing so would result in was profoundly chilling. My partner felt she could not continue watching the series after the episode in which we see the circumstances of Brendan's confession, and while I was disappointed to watch the rest alone, I understood. I could too easily picture our daughter in that little room, saying whatever she was told to because a big man kept claiming everything would be OK if she did). The second tale is about the justice system, and that is why the show perhaps needs to be biased.

We need to have sympathy for Avery if we are to be able to see the justice as flawed, and its power as terrifying. If we knew out the gates that Avery was indeed a violent sex criminal, we'd be rooting for the state to take him down by almost any means necessary. We've often had that frustration in TV shows such as the Wire - when the police aren't able to get someone they know for sure is a dangerous criminal convicted, we're praying that one of them takes the law into their own hands to make things right. Making A Murderer has to get past the inherent trust of justice that many of us broadly have in order for us to see how it can be perverted, and to achieve that it has to put us on the accused's side.

It's biased. It's extremely biased. It doesn't tell us how much contact Avery had with his alleged victim even on the very day she went missing, it doesn't tell us about the history of violence and sexual assault in his family, and it handwaves away even the declared fact that he once burned a cat alive. It doesn't, however, come out and say that he wasn't behind the murder, and thus, whatever ultimately happens, it can stay it stopped short of proclaiming a monster's innocence. But in order that we can see the lengths police will go to to get their man - planting evidence, stealing blood, refusing to look into someone else's confession, letting another known criminal go free so they can focus on Avery, coercing someone with learning difficulties into saying what they wanted to hear, then lying about it all - perhaps Making A Murderer had to be biased.

Avery may well be guilty. There are an awful lot of coincidences to be explained away if he isn't. But what if he isn't? More terrifyingly, what if this happened to you or me? What hope would we have when the system is like that? When law cheats and colludes, when entire juries wind up lead by an aggressive minority regardless of individuals' feelings, when lawyers set up their own clients for a fall, when the accused's options to fight back run out once the money does? What could we do?

I ejected out the other end of Making A Murderer chilled, then dismayed to discover that it was already everyone's talking point. But, for once, I don't think this one's getting out of my head any time soon.